The aim of this essay is to interrogate the relationship between Deleuze’s concepts of Idea, creativity, and control societies, alongside its interpretation by Paul Patton and Godard’s efficacy at giving these concepts their proper audio-visual form in cinema. By means of Godard’s Alphaville, we will demonstrate how Deleuze’s understanding of the relation between Ideas, creativity, and control differs in important ways from the interpretation offered by Patton. Using Alphaville as the means to distinguish between Patton’s and Deleuze’s own thought on cinema will be useful for two main reasons. First and foremost it is with Alphaville that Godard would achieve in cinema what Deleuze only put to paper late in his life: the presentation and analysis of a society of control with its specific power dynamics and affective determination of the mass individual. Second, highlighting this point of convergence between artist and philosopher will serve as the grounds for our engagement with the widely accepted ‘affirmationist’ interpretation of Deleuze’s thought; an interpretation that treats the ‘intensification of differences’ as ontologically correct and the proper socio-political guideposts for any kind of intentional resistance to the advances made by capital.

This interpretation is clearest seen in Paul Patton’s, ‘Godard/Deleuze: Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie).’ For Patton, the pessimism Godard expresses regarding gender roles in Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie) is merely a pretext for a redemptive reading of a becoming-woman, which prescribes an ethico-aesthetics of an “affective optimism and affirmation of life. (additionally – it is because Patton applies Deleuzian concepts to Sauve Qui Peut, that I term this an ‘affirmationist’ interpretation). For Patton, what is essential for Deleuze’s thinking regarding cinema is succinctly stated as follows: Deleuze and Guattari accord an ethical and ontological priority to those modes of existence which allow the maximum degree of movement, for example, forms of nomadism or rhizomes. In this sense, their philosophy embodies a vital ethic which affirms the creative power of life, even if this is something a non-organic life tracing the kind of abstract line we find in art or music.[1]

However, as we will see in what follows, Patton’s interpretation of Godard, and use of Deleuze, simply reintroduces Platonism back into the heart of Deleuze’s thoroughly anti-Platonist commitments – whether considered within the domain of philosophy, art, science, or politics. By grounding Deleuze’s vitalism on the principle of life’s inherent creativity, Patton proposes a “Deleuzian” ethics and politics whose fundamental aim is the application of these metaphysical, social, and aesthetic principles (becoming-x, lines of flight, and so on) within the domains of art and politics. As is well known, it is precisely this idea of taking what is metaphysically True as the means for executing what is aesthetically and politically Good that is the trademark of Platonism.

In order to understand the discrepancy between the Platonism of Patton and anti-Platonism of Deleuze, Godard’s Alphaville will serve as a link between the two. Alphaville serves as the aesthetico-political test to which we must subject Deleuze’s and Patton’s thoughts regarding cinema since it not only represents a society of (cybernetic) control, thereby posing the problem of how one escapes, evades, or subverts such social conditions. Additionally, by viewing Godard, Patton, and Deleuze through the lens of the aesthetico-political determination of the ideas of control, creativity, resistance, we will get a better sense of how our interpretation of Deleuze draws the portrait of a thinker better suited for analyzing societies of control and constructing various means of true resistance, while Patton’s interpretation reads into the works of Deleuze a kind of willful collapse of metaphysics into politics, where by the truths of the former become the ends to be realized in the latter.

I. An Apology for Life’s Creative Powers

What are we to make of Patton’s claim that Deleuze and Guattari give ethical and ontological priority to modes of maximizing one’s degrees of movement (rhizomes, nomads), such that this priority is tantamount to an affirmation of the creative powers of life? On Patton’s reading, what is key for understanding Deleuze’s relationship to cinema is this lasting commitment to the priority of a maximization of joyful encounters over and against the secondary fact of what is created in the process itself. The affirmationist interpretation takes what Bergson termed élan vital as the principle of what is truly revolutionary within the aesthetic or political domain, thereby relegating this élan’s products as mere consequence of what exists as ontologically and politically prior. Thus Godard’s Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie), which Patton reads as emblematic of Deleuze’s aesthetic theory, is presented as a meditation on gender as a zone of indistinction where the norms that underpin the gender binary are called into question. For Patton, it is precisely the unresolved dilemma regarding masculine social norms that gives one the impression of Godard’s pessimism regarding young men in post war France. However, this pessimistic impression of masculinity is only a pretext for the optimism that lies in the potential of a becoming-woman. As Patton writes, “this pessimism about the male condition is not only circumscribed but contrasted with an optimism about life, albeit a life which has become feminine…The result is an affective optimism and affirmation of life which attaches itself above all to images of women engaged in an active becoming of their own.”[2]

Thus, what first appears as Godard’s pessimism is simply indicative of a more fundamental optimism; an optimism that requires an affirmation of the becoming-woman at the heart of the dilemma of masculinity. Moreover, by invoking the Godardardian principle, ‘not just ideas, just ideas’, Patton reads this becoming-woman as being privileged by Deleuze and Guattari since lines of flight and becomings are creative in themselves and harbor the potential for transformation and novelty. For Patton, a cinema or thought that operates by way of correct ideas (just ideas), as opposed to just having ideas, tends toward the ossification of power and the repetition of all the pitfalls already exhibited by historical communism:

The task of philosophy, they suggest, is not to produce correct ideas, but simply ideas such that, when placed alongside ideas from other domains, there is the possibility that further ideas will emerge, through capture, exchange or cross-fertilisation of contents. The other approach, ‘correct ideas’, makes obvious reference to Mao’s question ‘where do correct ideas come from?’. Deleuze and Godard were both involved in the predominantly Maoist style of leftism which flourished in France between 1968 and 1975. Their rejection of the politics of the correct line is a rejection of the tendency to conformism and dogmatism which it encourages.[3]

That is, Deleuze and Guattari view correct ideas as privileging “conformism and dogmatism.” Thus, according to Patton, they maintain “a rejection of any subordination to intellectual authority which inhibits creativity.”[4] This is the crux of the affirmationist interpretation: lines of flight, becoming-minor, rhizome-books, and so forth, are taken to be axiomatic to Deleuze (and Guattari’s) understanding of aesthetics, ethics, and politics. For Patton, anything that inhibits the creative potential of these lines of flight is seen as reactionary pure and simple. While Patton’s interpretation contains some kernel of textual truth, errors arise insofar as Deleuze and Guattari are interpreted as valorizing becoming and transformation for its own sake and on the basis of the idea that the creative powers of life are the ethico-political guideposts for aesthetic and political practices. The affirmationist interpretation correctly highlights Deleuze’s emphasis on ambiguity, lines of flight, and the inherent quality of resistance in artistic production. However, this interpretation misconstrues how Deleuze views the emancipatory potential of each of these categories within cinema itself. That is, and against the affirmationist interpretation, not only does Patton commit himself to an approach to cinema [5] that Deleuze explicitly rejects, Patton misunderstands Deleuze’s vitalism, which is in fact a theory of time and not a theory of some universal life force, and thereby conflates a faith in life’s inherent creativity with an aesthetico-political concept of resistance, change, and liberation.[6]

Since Patton maintains that vitalism is a theory of life as opposed to time, his affirmationist interpretation simply perpetuates the popular yet misguided idea that Deleuze satisfied himself with following whatever is the most deviant, the most subversive, and the most minor in philosophy, art, and politics on the basis that deviancy, subversiveness, and minority are desirable-in-themselves precisely because they are our means of access to what is metaphysically determined as qualitatively transformative. On this view, one affirms their becoming-minor and the subversiveness it entails simply because it accords to the higher metaphysical claim of life’s inherent creativity. That is to say, insofar as our aesthetic and political engagements exist as perfect copies of the metaphysical and vitalist principle of creativity, then, we can safely judge actions as aesthetically, ethically, and politically virtuous, or revolutionary. At this point we should pause to highlight at least three themes that are equivocated, which allow the affirmationist interpretation to function: vitalism, the affirmation of life as tantamount to the production of novelty, and the status of indeterminacy/indistinction as effected by cinema itself.

II. Vitalism

Deleuze’s ‘vitalism’ is not reducible to a theory about the inherent capacities of life as creative. Rather, it is a theory of the nature of time and time’s foundational relation to space. It is the problem posed by the nature of time, moreover, that is precisely what motivates Deleuze’s voyage into cinema. As he writes,

Time is out of joint: Hamlet’s words signify that time is no longer subordinated to movement, but rather movement to time. It could be said that, in its own sphere, cinema has repeated the same experience, the same reversal, in more fast-moving circumstances…the post-war period has greatly increased the situation which we no longer know how to react to, in spaces which we no longer know how to describe…Even the body is no longer exactly what moves; subject of movement or the instrument of action, it becomes rather the developer of time, it shows time through its tiredness and waitings.[7]

The interpretation that sees a vitalism at work within Deleuze’s analysis of cinema is correct insofar as what is meant by vitalism is the problem posed by the nature of time to philosophy, art, politics, and science. It is for this reason that Bergson becomes an instructive thinker for Deleuze’s turn to cinema since what preoccupied Bergson, and what Deleuze finds at work in post-war cinema, is precisely the attempt to reverse the classical idea which thinks the reality of time as subordinate to, and dependent upon, the nature of space.

As Deleuze (following Bergson) makes clear the intelligibility of Life-in-itself is never grasped, as Aristotle thought, through the definition of time as the measure of movement in space; a definition which posits the essence and actuality of time as dependent upon space for its own existence. If time is not ontologically dependent on space as Bergson maintains; and if time is not reducible to the linear progression of the measure of movement; then this conception of time-itself requires a reconceptualization of the very lexicon of temporality (past, present, and future). In Creative Evolution, Bergson gives his refutation of interpreting Life in terms of finality/final causes, and it is here where Bergson offers the means for a transvaluation of our temporal lexicon. On the ‘Finalist’ or teleological account of the reality of Time, the future finds its reality in the past and present, follows a certain order, and is guaranteed due to first principles. Thus, for the finalists, the future remains fixed and dependent upon the linear progression of time. For Bergson, the future is precisely that which does not depend on the linear progression of time for its own reality. In this way we can understand that for both Bergson and post-war cinema, the nature of time can no longer be understood as derivative of space as such.

So time must now be thought as that which conditions the reality of movement and space. And this can be achieved in cinema, says Deleuze, precisely by doing something only cinema can do. That is, by film’s capacity to produce a disjunct between the visual and the audible aspects of film: “The relations…between what is seen and what is said, revitalize the problem [of time] and endow cinema with new powers for capturing time in the image.”[8] If the ‘vital’ creativity of cinema is fundamental for Deleuze’s understanding of cinema, it is the case only insofar as cinema provides us with the means to no longer think of time as subordinate to space but as the problem that motivates and determines space itself. It for this reason that Deleuze will mark the shift from the movement-image to the time-image at the precise moment when cinema reformulated the problem posed to its filmic characters:

…if the major break comes at the end of the war, with neorealism, it’s precisely because neorealism registers the collapse of sensory-motor schemes: characters no longer “know” how to react to situations that are beyond them, too awful, or too beautiful, or insoluble…So a new type of character appears. But, more important, the possibility appears of temporalizing the cinematic image: pure time, a little bit of time in its pure form, rather than motion.[9]

Thus, Deleuze brings Bergson’s theorization of time (i.e. vitalism) to bear on cinema since what we discover is that time is both the object of Thought and cinema, and the productive principle of any actualized and lived reality. Thus, the vitalist tendencies of Deleuze’s remarks on cinema should not be seen as a theorization of the creative powers of life. If vitalism is somehow a theory regarding what is principally creative within the world, it is not ‘Life’ but time-as-such that is creative. Moreover, what is produced by time-itself and cinema’s time-image is problematic in nature. Thus, not only is vitalism a theory about time (and not life); time-as-such does not produce something that can easily be judged as good or bad; virtuous or vicious. Rather, time produces problems for us; problems whose solutions can only be determined insofar as Thought and cinema pose the problem truthfully as opposed to preoccupying itself with false problems.

III. Novelty & Creativity

If Deleuze’s vitalism is a theory of time and the problem posed by Time for Thought and cinema, then the ‘creative powers’ attributed to this vitalism must also undergo redefinition. The interpretation of Deleuze’s aesthetic and political theory as one that seeks to adequate, in thought and praxis, Life’s inherent creativity and novelty fails to account for Deleuze’s anti-Platonism, where the relationship between models and copies is jettisoned for the relationship between simulacra and the Idea-problems to which they are indexed. As Deleuze writes in Difference and Repetition regarding the relationship between optimism and the relationship between Thought and its Ideas/problems:

The famous phrase of the Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, ‘mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve’, does not mean that the problems are only apparent or that they are already solved, but, on the contrary, that the economic conditions of a problem determine or give rise to the manner in which it finds a solution within the framework of the real relations of the society. Not that the observer can draw the least optimism from this, for these ‘solutions’ may involve stupidity or cruelty, the horror of war or ‘the solution of the Jewish problem’. More precisely, the solution is always that which a society deserves or gives rise to as a consequence of the manner in which, given its real relations, it is able to pose the problems set within it and to it by the differential relations it incarnates.[10]

Thus, the idea of simply pursuing various lines of actualization vis-á-vis a specific set of Ideas/problems, thereby embodying the perfect copy of the creative potential of the problems posed to us by life itself, is seen as suspect by Deleuze himself if for no other reason than what is given to Thought in the Idea-Problem is every possible solution. Every possible solution includes, as seen in the passage above, both the horrors of fascism and the aspiration of social and political liberation. If, as Patton encourages us to believe, Deleuze’s aesthetic/political theory simply amounts to affirming the novelty of life, we would commit ourselves to the position of accepting every solution to social and political problems. While it is true for Deleuze that Idea-problems pose every possible solution from the outset, it is also the case that each possible solution to an Idea-problem can be actualized only on the condition that one solutions unfolding (explication) maintains an incompossible relation to all other solutions. Solutions to a problem, thus, are actualized according to their exclusive disjunction with an Idea-problems other possibilities. This thesis of incompossibility in regards to the relation between problems and their resolution is what is at stake when Deleuze writes:

The I and the Self…are immediately characterised by functions of development or explication: not only do they experience qualities in general as already developed in the extensity of their system, but they tend to explicate or develop the world expressed by the other, either in order to participate in it or to deny it (I unravel the frightened face of the other, I either develop it into a frightening world the reality of which seizes me, or I denounce its unreality).[11]

However, why have we said that Patton’s affirmationist interpretation reintroduces Platonism into Deleuze’s thought? For the following reason: once we understand that Deleuze’s vitalism is a theory of time and not a theory of life; and once we grasp that what time produces are Idea-problems prior to their resolution; the priority given to Idea-Problems by Deleuze can only be a priority of metaphysical and epistemic inquiry and not moral in character. Patton’s affirmationist interpretation, which takes Idea’s as a legislative-model for ethical, political, or aesthetic action reintroduces Platonism in the heart of Deleuze’s thought since the equation of metaphysics (Idea/model) with politics (claimant/copy) necessarily entails the logic of the good and bad copy, the true and false claimant. Patton’s reading reintroduces what is inessential to Ideas (moral criteria of judgment) back into their essence (qualitatively different claimants to an Idea), and thereby reduces what is truly creative for Thought (Problems) to something to be subjected to ready-made criteria (Image of Thought):

This Platonic wish to exorcise simulacra is what entails the subjection of difference. For the model can be defined only by a positing of identity as the essence of the Same…and the copy by an affection of internal resemblance, the quality of the Similar…Plato inaugurates and initiates because he evolves within a theory of Ideas which will allow the deployment of representation. In his case, however, a moral motivation in all its purity is avowed: the will to eliminate simulacra or phantasms has no motivation apart from the moral.[12]

Thus, it is by the confusing the ontological and epistemic with the aesthetic and political, that Patton’s affirmationist reading reintroduces Plato’s moralism back into Deleuze’s philosophy of Difference.

IV. Indeterminacy & Falsity

The third and final point regarding the status of indeterminacy/falsity in cinema as presented in the affirmationist approach can be seen in the following passage. For Patton, and regarding the status of normative gender roles in Sauve Qui Peut, Godard “offers no solution to this dilemma of masculinity…Ultimately, this pessimism about the male condition is not only circumscribed but contrasted with an optimism about life, albeit a life which has become feminine…The result is an affective optimism and affirmation of life which attaches itself above all to images of women engaged in an active becoming of their own.”[13] What is missing from Patton’s account, however, is the precise relationship between the indeterminacy of social norms as seen in Sauve Qui Peut as they relate to what cinema’s time-image achieves: namely, the power of falsity that reintroduces indeterminacy/indistinction (molecular) into that which remains determinate and distinct (molar). As Deleuze writes, “[T]he power of falsity is time itself, not because time has changing contents but because the form of time as becoming brings into question any formal model of truth.”[14]

If Godard resists resolving the dilemma of masculinity, it is not because there is no answer to the problem of hetero-patriarchy. Rather, it is because only by making the determinate/distinct into something indeterminate/indistinct that cinema moves beyond merely representing different solutions of a problem to the immediate presentation of the problem via the time-image. It is time (as the form of becoming) that creates the indistinct and undecidable character of the lived reality of hetero-patriarchy in Sauve Qui Peut; and Godard achieves this in cinema through a direct presentation of a problem over and against the presentation of its various solutions. Remarking upon this relationship between truth and falsity, indistinction and undecidability, Deleuze remarks:

The real and the unreal are always distinct, but the distinction isn’t always discernible: you get falsity when the distinction between real and unreal becomes indiscernible. But, where there’s falsity, truth itself becomes undecidable. Falsity isn’t a mistake or confusion, but a power that makes truth undecidable.[15]

The powers of the false; the immediate presentation of a problem; renders truth undecidable and the relation of the true and the false indiscernible precisely because this immediate presentation of a problem “brings into question any formal model of truth. This is what happens in the cinema of time.”[16] Just as the philosopher cannot hope for any optimism in their proper orientation toward Ideas, the filmmaker does not predict any certain or clear solution in their immediate presentation of a problem. For both philosopher and filmmaker, the true posing of Idea-problems troubles our ready-made models because, as Deleuze says of Godard in an interview, “the key thing is the questions Godard asks and the images he presents and a chance of the spectator feeling that notion of labor isn’t innocent, isn’t at all obvious.”[17] Insofar as philosopher’s pose true problems and create concepts adequate to them; insofar as filmmakers present problems in their immediacy in terms of the time-image; each creates something which no longer allows others to treat ideas, concepts, or images as ready-made, neutral, and naturally given features of the world. The posing of true problems in thought and cinema is the genesis of a concept, or artwork, that disrupts our habituated modes of thinking, feeling, and approaching the world (i.e., the dogmatic image of thought). The power of falsification is cinema’s capacity to render what we take to be obvious, ready-made, or second nature as alien and no longer a fixed socio-political certainty. The powers of the false and a cinema of undecidability, then, are Godard’s means of effecting a becoming since he “brings into question any formal model of truth.”[18]

If Sauve Qui Peut offers no solution to the problem posed by hetero-patriarchy and thus remains indeterminate; and if this problem reveals the condition of masculinity as being one that requires a becoming-woman; the indistinctness/undecidability of becoming-as-such is much more a counter-actualization rather than an actualization of a solution with respect to its problem. The main consequence of Patton’s equation between the (ontologically) True with the (ethically) Good or (politically) Just results in a case of misplaced concreteness whereby Deleuze appears to valorize the application of ontological truth into the realm of aesthetico-political activity. With Patton, we find a Deleuze who would never have found troubling the moralism at the heart of Platonism; who never would have written that philosophers and filmmakers alike should follow the maxim that says “Don’t have just ideas, just have an idea (Godard).”[19]

V. The Affirmationist Interpretation

Given what has been shown regarding the themes of vitalism, novelty/creativity, and undecidability/falsity, we can summarize Patton’s affirmationist interpretation of Deleuze in the following manner: by treating vitalism as a theory of life and life’s inherent creative powers Patton proposes a Deleuzian ethics and politics whose fundamental aim is the application of metaphysical and epistemic principles within the domains of art and politics. However, as we have seen, this interpretation reintroduces Platonism back into Deleuze’s strictly anti-Platonic thinking regarding the relationship between Ideas, the possible solutions they propose, and the thinkers relation to the two. In contradistinction to Deleuze’s anti-Platonic commitments, Patton interprets ‘the creative powers life’ as ready-made criteria for the judgement between good and bad copies, between better or worse claimants to an Idea. On this reading of Deleuze what is ‘True’ regarding the nature and structure of reality (inherent creativity of life) is also interpreted as what is ‘Good’ for individual and social life. It is on this basis that Patton can claim that the essence of Deleuze’s political commitments can be summarized as a repudiation of anything that inhibits modes maximization of movement and creative powers.

Hence our nomination of Patton’s reading of Deleuze as Platonic in essence – when the True is also the Good we should know that we are not far from discovering a Plato in our midst. Additionally, even at the moment when Patton’s reading seems to gain most support from his analysis of gender roles within Godard’s film his proposal of a becoming-woman at the heart of a perceived pessimism regarding young men (while true) remains at the level of the most basic generality. In other words, lines-of-flight may give us insight into the available means for the subversion of power or the escape from control, but lines-of-flight themselves are not in-themselves revolutionary. Thus, Patton’s reconstruction of a Deleuzian ethico-politics excludes the principle of non-identity between lines-of-flight, deterritorialization, smooth space and the revolutionary transformation of society, that Deleuze and Guattari continuously return to throughout their joint works. As the well known Deleuzo-Guattarian saying goes, “smooth spaces are not in themselves liberatory.”[20]

Thus, our suspicion of Patton’s interpretation stems from the claim that Deleuze’s preoccupation with Idea-problems is not simply a continuation of their Platonic ancestors. On this affirmationist/Platonist interpretation, Deleuze appears to locate the creativity and novelty of art (and Godard’s cinema in particular) at the register of the cinematic representation of specific concepts (lines of flight, becoming-woman, becoming-minor). It is in this way that Patton reads the pessimism which Godard expresses regarding gender roles as a mere pretext for the redemptive theme of becoming-woman. And it is precisely the cinematic representation of the redeeming theme of becoming-woman that Patton takes to be Deleuze’s own prescription of an ethico-politico-aesthetics that can be adequately summarized as an “affective optimism and affirmation of life.” However, if philosophy and cinema are creative insofar as they can pose a problem correctly, an optimism or affirmation of life does not follow necessarily since it is precisely the distinction and determination of truth and falsity, the real and the unreal, that is rendered undecidable by problems themselves. The activity of philosophy and filmmaking follow a different outcome, whereby each individual cannot draw the least amount of optimism from solutions of the problem “for these ‘solutions’ may involve stupidity or cruelty, the horror of war or ‘the solution of the Jewish problem.’”[21]

Given our critique of the affirmationist interpretation, and while Godard’s Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie) is Patton’s exemplar of something that approximates a Deleuzian ethico-political program, we should turn our attention to Godard’s 1965 sci-fi noir film Alphaville as the measure (and critique) of this affirmationist reading. Turning to Alphaville is crucial since it is the film where Godard achieves in cinema what Deleuze himself would only put down to paper towards the end of his life: the problem of how one makes revolution from within the contemporary paradigm of control societies. Not only were societies of control emerging as the latest form of capitalism’s ongoing globalization in Deleuze’s own life time; specific for our purposes here, what Deleuze understands as the technical and material conditions of control societies is precisely what Godard explores through the figure of an artificially intelligent computer (Alpha 60) that regulates the city of Alphaville as a whole with the aim of ensuring ‘civic order’ and dependable (i.e., predictable) citizenry. It is Alpha 60 who surveils, polices, and determines the guilt or innocence of the citizenry; that is, this AI form of governance is the perfect instance of those cybernetic machines [22] at work in capitalist-control societies. Additionally, this emerging problem of control was a consequence of the shift from the ‘movement-image’ to the ‘time-image,’ as Deleuze notes. It is a shift to the paradigm that “registers the collapse of sensory-motor schemes: characters no longer “know” how to react to situations that are beyond them, too awful, or too beautiful, or insoluble…So a new type of character appears.”[23]

However, what Deleuze leaves implicit and undertheorized in his concept of the ‘time-image,’ is the following: if it is after the second world war where we see a shift from the ‘movement-image’ to the ‘time-image,’ there was a simultaneous shift in how nation-states began to conceive of the role of government as such. During and after the war, information theorists, scientists, and academics were employed by the American government to develop the technological means for establishing a certain degree of civic order in a world that has proven itself capable of succumbing to the ever looming threat of global war. It was this emerging group of scientists and academics that would construct the very means for actualizing societies of control (Deleuze) and were the real world correlates for the social function of Alpha 60 (Godard):

the very persons who made substantial contributions to the new means of communication and of data processing after the Second World War also laid the basis of that “science” that Wiener called “cybernetics.” A term that Ampère…had had the good idea of defining as the “science of government.” So we’re talking about an art of governing whose formative moments are almost forgotten but whose concepts branched their way underground, feeding into information technology as much as biology, artificial intelligence, management, or the cognitive sciences, at the same time as the cables were strung one after the other over the whole surface of the globe […] As Norbert Wiener saw it, “We are shipwrecked passengers on a doomed planet. Yet even in a shipwreck, human decencies and human values do not necessarily vanish, and we must make the most of them. We shall go down, but let it be in a manner to which we make look forward as worthy of our dignity.” Cybernetic government is inherently apocalyptic. Its purpose is to locally impede the spontaneously entropic, chaotic movement of the world and to ensure “enclaves of order,” of stability, and–who knows?–the perpetual self-regulation of systems, through the unrestrained, transparent, and controllable circulation of information. [24]

Whether we speak of the paradigm of control in contemporary modes of governmentality or Alpha 60 in Alphaville, both Deleuze and Godard are concerned with the possibilities for the radical transformation of social life from within this context of cybernetic governance. Thus, it is against the background of societies of control that Patton’s affirmationist interpretation, and the politics that logically follow, will be measured and tested; if only to underscore how the affirmationist’s Platonism demonstrates that the application of metaphysical and epistemic truths into the domain of politics culminates in a praxis that is impotent at best and reactionary at worst.

VI. Alphaville & Control Societies

Sometimes reality is too complex for oral communication. But legend embodies it in a form, which enables it to spread all over the world. These are the opening lines of Godard’s sci-fi noir film Alphaville (1965), which tells the story of secret agent Lemmy Caution as well as what he sees and who he encounters in Alphaville, all during his officially stated business of tracking down a certain Dr. von Braun. Upon arrival, we realize, along with Lemmy Caution, that the citizens of Alphaville are individuals who have been made to feel contented in indulging various drug habits, or who have been assigned the social task of providing ‘escort’ services (a service done only by women in the film) for business persons (all who are men) and citizens alike, or who were once secret agents like Lemmy himself, but have succumbed to the demands of life in the city. Despite the clean and ordered appearance of the city’s architecture and infrastructure, Alphaville is not a place whose order and structure aims to support the daily life of individuals but rather a metropolis organized to reproduce the social roles/functions necessary to reproduce its existence.

In order to ensure this reproduction of the metropolis and its necessary social functions, Alphaville has instilled in its citizens a mode of relating to the world that accords to the following maxim:“No one ever says ‘why;’ one says ‘because.’”[25] Thus, the citizens of Alphaville have all been socialized (whether from birth or due to threat of violence and death) into substituting questions that pertain to sufficient reasons and justifications for questions that pertain to causal explanations. In other words, the people of Alphaville have been habituated to treat causal explanation (“because”) as synonymous with rational justification (“why”). It is due to this situation where causal explanation is identical to rational justification that Lemmy’s former colleague Dickinson, makes this following remark upon their reuniting: “Their ideal here, in Alphaville, is a technocracy, like that of termites and ants.”[26] For Dickinson, a life lived in Alphaville means to be governed and treated as a part of an organic whole; a part who requires attention and support only to the extent that all individuals can fulfill their function of maintaining Alphaville’s social organization.

Later in the film, and alongside our main character, we learn the reason for this ideal of technocracy: Alpha 60, an artificially intelligent super-computer, monitors Alphaville’s inhabitants with the aim of maintaining a certain order and stability in the city as a whole. Alpha 60 serves as the police, the government, the judges and the jury, and whose authority stems from its superhuman capacity for computational analysis. With respect to this form of cybernetic governance, Alpha 60’s sole interest lies in determining which individuals of the population are capable of being socialized into civil society and which individuals are unassimilable and therefore must be exterminated. Godard shows his audience the effects of this cybernetic organization of social life clearest in the scene (below) where Lemmy Caution is brought to witness the execution of citizens whose crime was simply having behaved illogically.

Given the organization of Alphaville, and from the dialogue in the scenes above, we are compelled to say that this is precisely what Deleuze and Guattari describe when speaking of the abstract machine of faciality:

…the abstract machine of faciality assumes a role of selective response, or choice: given a concrete face, the machine judges whether it passes or not, whether it goes or not, on the basis of elementary facial units. This time, the binary relation is of the “yes-no” type…A defendant, a subject, displays an overaffected submission that turns into insolence. Or someone is too polite to be honest…At every moment, the machine rejects faces that do not conform, or seem suspicious. [27]

If Alphaville has something in common with Deleuze’s concept of control societies, and with Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of abstract machines of faciality, it is with regard to the question of contemporary forms of governance whose means are becoming less those of confinement and more so those of ensuring the aggregation of information, its transparency, in order to better surveil and control populations. We can see Godard’s concern with the set of problems of control and governance, of resistance and ordered obedience, in the conversation between Lemmy Caution and Alpha 60 at the end of the film:

Alpha 60: You are a menace to the security of Alphaville.

Lemmy Caution: I refuse to become what you call normal.

Alpha 60: Those you call mutants form a race superior to ordinary men whom we have almost eliminated.

Lemmy Caution: Unthinkable. An entire race cannot be destroyed.

Alpha 60: I shall calculate so that failure is impossible.

Lemmy Caution: I shall fight so that failure is possible. [28]

In light of this final dialogue, two things are worth noting. First, the antagonism between Lemmy Caution and Alpha 60; between the symbol of liberation from cybernetic governance and the symbol of control societies; takes the form of a struggle over what is deemed as possible and impossible. That is to say, not only is it the case that cybernetic governance is a form of control since it seeks to pre-emptively foreclose the possibility of the radical transformation of society. More importantly, and regarding the relation between Deleuze and Godard, it is precisely in the domain of the existence or inexistence of possibility that Deleuze locates the radical potential of both cinema and political change. As Deleuze writes in his now oft cited passage

Which, then, is the subtle way out? To believe, not in a different world, but in a link between man and the world, in love or life, to believe in this as in the impossible, the unthinkable, which none the less cannot but be thought: ‘something possible, otherwise I will suffocate.’ It is this belief that makes the unthought the specific power of thought, through the absurd, by virtue of the absurd. [29]

If ‘belief’ is the concept that offers the potential for freeing ourselves from control societies, it must be understood in the terms of the debate between Lemmy and Alpha 60. Determining what is possible and impossible becomes the contested site of politics, where the revolutionary, reformist, or reactionary character of one’s politics is put to the test and ultimately revealed. In terms of Alphaville, it is clear that Lemmy Caution is a symbol of belief; the one who struggles for what is calculated as an impossibility from the perspective of the society of control regulated by Alpha 60 itself. Second, and regarding the relationship between Alphaville and the emergence of cybernetics as form of governmentality in general, one cannot be faulted for thinking that Godard himself created Alpha 60 simply from the aims and ambitions of the marriage between cybernetics and government as outlined by the French Information theorist Abraham Moles:

We envision that one global society, one State, could be managed in such a way that they could be protected against all the accidents of the future: such that eternity changes them into themselves. This is the ideal of a stable society, expressed by objectively controllable social mechanisms.[30]

Given this situation of control as the dominant form of governance in both Alphaville and contemporary capitalism, of what use could we make of Patton’s affirmationist politics? Does Alphaville and our present day control society violate the vitalist principle of the inherent creative powers of life and obstruct the experience of joyous encounters? In other words, with control societies as well as Alphaville do we encounter an organization of social life such that there is an obstruction, or violation, of the essential productivity that defines the nature and structure of reality as well as the fundamental feature of living beings as such?

For Patton, the answer is straightforwardly affirmative: whether we consider Alphaville or societies of control, what we can be certain of is the ongoing violation of the creative powers of individuals in society and an obstruction of the possibility of living a life defined by joy as opposed to sadness. And it is precisely in this affirmative response that we see how Patton’s reconstruction of ‘Deleuze’s’ metaphysical and epistemic commitments undercut any possibility for an ethico-political paradigm that can make good on the aspiration of the fundamental transformation of capitalist society into full communism as such: when what is understood to be metaphysically true (inherent creativity/productivity of life) is then used as the socio-political means to resist capitalist control, one may very well end up with a politics that privileges affirmation and creativity but it would not be a politics that necessarily coheres with that of Deleuze. For example, as Deleuze and Guattari state in the very first pages of Anti-Oedipus, this vitalist principle of continuous productivity and creation may be metaphysically significant but cannot be confused with, or projected as, a program for real political intervention. As they write, “There is no such thing as either man or nature now, only a process that produces the one within the other and couples the machines together.”[31] Or even closer to our critique of Patton’s affirmationist interpretation:

Even within society, this characteristic man-nature, industry-nature, society-nature relationship is responsible for the distinction of relatively autonomous spheres that are called production, distribution, consumption. But in general this entire level of distinctions, examined from the point of view of its formal developed structures, presupposes (as Marx has demonstrated) not only the existence of capital and the division of labor, but also the false consciousness that the capitalist being necessarily acquires, both of itself and of the supposedly fixed elements within an overall process. For the real truth of the matter [is]…everything is production.[32]

Thus we can see that while it remains true at the level of the nature of flows and becomings that there is some creative capacity to which human society and economic production remains intractably subject to, it is also true that valorizing the creativity and productivity as such cannot discriminate between different political orientations. Patton’s affirmationist interpretation, which collapses its metaphysical claims into its political prescriptions, fails to account for Deleuze and Guattari’s own principle that everything is production; and this initial principle necessarily includes qualitatively different organizations of society (e.g., capitalist, communist, fascist). By equating what is essential for ‘life as such’ with what is desirable in the domain of politics, Patton precludes any possibility of differentiating between competing political alternatives to presently existing capitalism. Just as Power for Foucault produces more than it represses, for Deleuze and Guattari, every form of social organization is inherently productive, albeit in specific and incompatible ways. So if Patton’s criteria vis-à-vis his affirmationist position is the freeing up of productivity wherever it is stymied, then the politics that stems from this principle affirms any and all organizations of social life necessarily since every form of society is productive in its own way.

One of the major consequences of such a position is that Patton subtracts our capacity for proposing alternative visions of the world in relation to present circumstances. In depriving ourselves of the capacity for proposing an alternative to our present, not only does Patton’s political position exacerbate the very problem Deleuze took as the problem posed to the project of revolutionary transformation; Patton’s position also appears as a deviation from the very category of creativity that Deleuze himself valorized in the domains of art, philosophy, and ultimately, politics: “We lack creation. We lack resistance to the present…Art and philosophy converge at this point: the constitution of an earth and a people that are lacking as the correlate of creation.”[33] If Deleuze retains some place in his political framework for the category of creativity, it must be understood not as the most general feature of reality and rather as the construction of an alternative to the present. In order to create something that is against our time, we require the capacity of discriminating between alternatives; and this capacity of discriminating between alternative futures is precisely what is foreclosed by necessity on Patton’s interpretation of Deleuze. By ignoring Deleuze’s specific usage of the category of creativity in the realm of politics, Patton’s position necessarily affirms everything–since, according to Deleuze and Guattari’s own principle everything is productive–and therefore gives rise to a politics devoid of content or prescriptions, and remains abandoned to the machinations of the present.

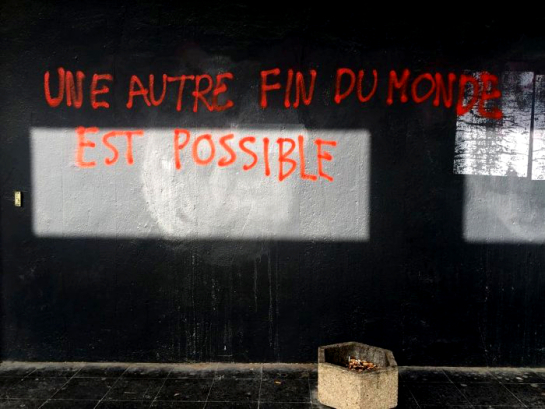

VII. An other end of the world is possible!

By way of conclusion, we offer the following hypothesis: an other end of the world is possible. This statement ties together our critique of Patton, the emphasis Deleuze places (in cinema and politics) on the struggle for alternate and possible worlds in light of its seeming impossibility from the perspective of control societies, and the political category of creativity and resistance. In our present circumstance it’s worth reiterating the point made by Guattari in his reflection on the progress made by capitalism after the events of ‘68:

Capitalism can always arrange things and smooth them over locally, but for the most part and essentially, everything has become increasingly worse […] The response to many actions has been predicted organized and calculated by the machines of state power. I am convinced that all of the possible variants of another May 1968 have already been programmed on an IBM.[34]

This IBM which has predicted every possible future May ‘68 is to Alpha 60 as Deleuze’s concept of control societies is to our present. That is to say, and more to the point, present day control societies, with its cybernetic form of governance, is a form of social organization that takes as one of its axioms the pre-emptive powers derived from the control and permanent exchange of information in our present. In the situation where Alpha 60’s algorithmic powers of prediction equally determine the upstanding and problematic citizen; where cybernetic capitalism can create predictive models that run through every possible situation where an insurrection could take place; we find ourselves squarely in the contemporary manifestation of Clausewitz’s formula now with its contemporary twist: control is war by other means; these ‘other means’ being the politics of pre-emptive strategy supported by cybernetic technologies [35]

Even if the origins of the Internet device are today well known, it is not uncalled for to highlight once again their political meaning. The Internet is a war machine invented to be like the highway system, which was also designed by the American Army as a decentralized internal mobilization tool. The American military wanted a device which would preserve the command structure in case of a nuclear attack…With such a device, military authority could be maintained in the case of the worse catastrophes. The Internet is thus the result of a nomadic transformation of military strategy. With that kind of plan at its roots, one might doubt the supposedly anti-authoritarian characteristics of this device. As is the Internet, which derives from it, cybernetics is an art of war, the objective of which is to save the head of the social body in case of catastrophe. What stands out historically and politically during the period between the great wars…was the metaphysical problem of creating order out of disorder. [36]

In other words, the context of global warfare is continued through the constitution of Western government’s pre-emptive measures, which perpetually defer war itself in favor of what are now called ‘security measures,’ justified by a ‘war on terror.’ For as we have seen, it is at the end of the second World War that two important transformations took place: the shift in cinema from the ‘movement-image’ to the ‘time-image’ and the marriage between cybernetics, information theory, and modes of governmentality, this latter case being undertaken in order to prevent the global devolution of ordered and civil society. However, and against Patton’s interpretation, the ‘end of the world’ as conceived by the cybernetic paradigm of governance is a decidedly different apocalypse as the one viewed from the perspective of someone like Marx, for instance. When Marx talks about communism he is clear to say that it is not “a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself,” but the “real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.”[37] The type of abolition involved here is not the same type of abolition that is hinted at in the cybernetic fear of societal collapse since, for Marx as well as Deleuze, the proletariat that abolishes itself and capital in the process of revolution brings about the end of the world as determined by capitalist social relations and ushers in a new world determined by the needs and interests of labor considered as a whole. Is this not precisely what Deleuze suggests in his interview with Cahiers du Cinéma when he says,

Godard brings into question two everyday notions, those of labor and information. He doesn’t say we should true information, nor that labor should be well paid (those would be the just ideas). He says these notions are very suspect. He writes FALSE beside them. [38]

So, this other end of the world feared by cybernetic control appears desirable insofar as it means the end of this world; the end of the world governed on the basis of control, surveillance, and labor determined by capitalist social relations. So bringing about the ‘end of this world’ requires, on our part, a vision of alternative worlds that would come to take its place. It is this dimension of Deleuze’s aesthetic and political commitments that Patton fails to understand and thereby commits himself to the valorization of anything (and therefore, everything) that can be understood as metaphysically productive and creative. [39]

- Paul Patton. “Godard/Deleuze: Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie).” Accessed November 20, 2015. http://www.directors.0catch.com/s/Godard/La_vie_rev.htm., my emphasis.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Regarding the claim that Patton approaches cinema in a manner rejected by Deleuze, it is intended to underscore for the reader that Patton’s approach to Godard via Deleuze seeks to apply concepts from outside cinema (in this case concepts that come from Deleuze) and brings them to bear on the truth of cinema, or brings them to bear as a true measure of the power of cinema in its own right.

- Regarding this discrepancy between vitalism as a theory of life or a theory of time, John Mullarkey’s essay ‘Life, Movement and the Fabulation of the Event,’ is crucial. As he writes, “It takes only a little first-hand knowledge of Bergson’s texts to enable oneself to move beyond the stereotypical interpretation of Bergsonian vitalism as a notion regarding some mysterious substance or force animating all living matter. His theory of the élan vital has little of the anima sensitiva, archeus, entelechy, or vital fluid of classical vitalisms. This is a critical vitalism focused on life as a thesis concerning time (life is continual change and innovation) as well as an explanatory principle in general for all the life sciences.” John Mullarkey, ‘Life, Movement and the Fabulation of the Event,’ Theory, Culture & Society 2007 (SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore), Vol. 24(6): 53-70. p. 53.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), p. xi.

- Ibid, p. xiii

- Gilles Deleuze, ‘On The Time-Image,’ Negotiations, trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p. 59.

- Difference and Repetition, p.186. In addition, Deleuze writes “… ‘solvability’ must depend upon an internal characteristic: it must be determined by the conditions of the problem, engendered in and by the problem along with the real solutions” (DR, 162).

- Ibid, p. 260

- Ibid, p. 265

- ‘Godard/Deleuze: Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)’

- Negotiations, p.66.

- Ibid, p. 65-6

- Ibid, p. 66.

- Ibid, p. 40.

- Ibid, p. 66.

- Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University Minnesota Press, 1987 ), p. 25.

- Ibid, p. 500.

- Difference and Repetition, p. 162.

- The choice of the term cybernetics here is used in the sense first given to the word by one of its founders, Norbert Wiener: the science of control and communication in both living beings and machines. For Wiener, just it is for Deleuze and Godard, the type of governmentality that began at the end of the second world war slowly moved away from the disciplinary model based on confinement. Rather, the means of carrying out the best mode of governing a social body was to be accomplished by treating everyone problem regarding threat, risk, and the uncertainty posed by a world that has proved capable of global warfare as a problem of information: “Underlying the found of Cybernetics was a context of total war…Norbert Wiener…was charged with developing, with the aid of a few colleagues, a machine for predicting and monitoring the positions of enemy planes so as to more effectively destroy them. It was at the time only possible to predict with certitude certain correlations between certain airplane positions and certain airplane behaviors/movements. The elaboration of the “Predictor,” the prediction machine ordered from Wiener, thus required a specific method of airplane position handling and a comprehension of how the weapon interacts with its target. The whole history of cybernetics has aimed to do away with the impossibility of determining at the same time the position and behavior of bodies. Wiener’s innovation was to express the problem of uncertainty as an information problem…” ‘The Cybernetic Hypothesis,’ Tiqqun 2

- Negotiations, p. 59.

- The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, trans. Robert Hurley, (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2015), p. 107-9, my emphasis.

- Alphaville: A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution. Directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Athos Films, 1965. 00:50:06-00:50:10.

- Alphaville: A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution. 00:23:23-00:23:32.

- A Thousand Plateaus, p. 177.

- Alphaville, 01:17:45-01:18:32

- Cinema 2, p.170, my emphasis.

- Abraham Moles, cited in ‘The Cybernetic Hypothesis,’ Tiqqun 2, my emphasis.

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), p. 2.

- Ibid, p. 3-4.

- Gilles Deleuze and Fèlix Guattari, What is Philosophy?, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 108.

- Félix Guattari, ‘We Are All Groupuscules,’ Psychoanalysis and Transversality, trans. Ames Hodges (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2015), p. xx.

- The claim that our present geopolitical context still operates according to this criteria of order as opposed to disorder, civilization as opposed to societal collapse, is clearly seen in the 2014 Wall Street Journal article, ‘On The Assembly of a New World Order,’ authored by none other than Henry Kissinger himself. As Kissinger writes, echoing just the concerns of both post-war cyberneticians and Godard’s Alpha 60, ‘the very concept of order that has underpinned the modern era is currently in crisis.’ Thus, according to Kissinger and after the economic crisis of 2008 in a post 9/11 era, it is the recovery of global order based on the interests of American capitalism that is projected as the necessary task for Western powers today.

- ‘The Cybernetic Hypothesis,’ p. 9.

- Karl Marx, German Ideology

- Negotiations, p. 41.

- Regarding our conclusion, it is worth mentioning that a similar interpretation of Deleuze has been offered by Andrew Culp. As Culp writes in the conclusion to his Dark Deleuze, “The lesson to be taken is that “we all must live double lives”: one full of compromises we make with the present, and the other in which we plot to undo them…There are those whose daily drudgery makes it difficult to contribute to the conspiracy, though people in this position are far more likely to have secret dealings on the side. Others are given ample opportunities but still fail to grow the secret…Some treat the conspiracy as a form of hobbyism…the worst being liberal communists, who exploit so much in the morning that they can give half of it back as charity in the afternoon. And then there are those who escape. Crafting new weapons while withdrawing from the demands of the social, they know that cataclysm knows nothing of the productivist logic of accumulation or reproduction. Escape need not be dreary, even if they are negative. Escape is never more exciting than when it spills out into the streets…It is in these moments of opacity, insufficiency, and breakdown that darkness most threatens the ties that bind us to this world” (Culp, Dark Deleuze, pp. 69-70). For more see Dark Deleuze (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2016).

taken from here