Published at Multiwatch Swiss April 2020 , updated Feb.2022

In his article, Jan Braunholz describes how Nestlé determines the everyday lives of people in Mexico. The world’s largest food company, headquartered in Switzerland, dominates the market at all levels: from cultivation to coffee culture and consumption. Nestlé also influences the highest decision-making bodies of the Mexican government.

He is a journalist, docfilmer and coffeegrader as well as with the NGO Flüchtlingshilfe Mittelamerika e.V..

When I started shooting my film documentary ‘Cafe Rebeldia` about Zapatista coffee structures and the coffee crisis in Mexico 20 years ago, I didn’t realize how this world’s largest food corporation determines everyday life in Mexico. Starting from the cultivation to the coffee culture and consumption, they determine the market and also set the political cornerstones with concrete influence up to the highest decision-making bodies of the Mexican government. I will illustrate this with a few examples.

For years, Nestlé has been importing cheap Robusta green coffee from Vietnam, Brazil, Indonesia and Ecuador to Mexico for its Nescafe. There was constant protest from Mexican coffee producers against these imports. Nestlé’s idea was to grow Robusta coffee locally, and 20 years ago the first cultivation projects began in the area of Tezonapa in the state of Veracruz, which consequently became the epicenter of Nestlé’s coffee cultivation plans. As a result, the coffee producers became even more dependent because they have only one buyer, namely the Nestlé company with its upstream large intermediary AMSA (Agroindustrias Mexico S.A.), its coffee processing plant, the Beneficio, and its coyotes, the small intermediaries.

This is exactly what is happening again at the current harvest from January-March in Ixthuatlan de Café near Huatusco near Cordoba in the state of Veracruz. There is a large Beneficio of AMSA, which belongs to the ECOM coffee group.

They work as buyers for Nestlé and determine the price in the area. The more than 12,000 coffee farmers in the region can only deliver coffee cherries. In other parts of the country, they mostly buy café pergamino, the already cherry-less, hulled coffee that still has a pergamin skin. This is paid with approx. 25-30 Pesos/Kg (approx. 1 euro). I.e. Café Cereza brings them from the outset a bad price: approx. 4-5 pesos the kilo coffee cherries (approx. 20 Eurocent), for Nespresso with AAA surcharge approx. 7,50 pesos/kg. The actual Price February 2022 is beetween 13-15 Pesos /kg Cherrycoffee in Veracruz.

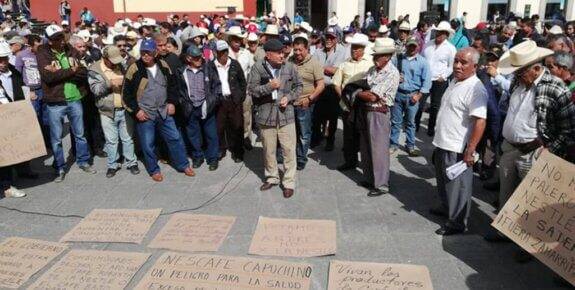

That was in early March 2020, when I was there – a pittance compared to the gigantic revenues Nespresso gets for its aluminum capsule espresso: about 70 euros per kilogram. Coffee farmer Carlos Hernandez Maduro put it bluntly: “It’s not profitable, the price is way down and it’s a very small crop.” This as a result of the Roya fungus plague, which has caused crop failures of 80-90%. They do not come up with the production costs and there have already been protests and roadblocks because of the pricing policy in front of the Beneficio, but to no avail.

The fact that the harvest revenues do not bring in the investments and are barely enough to survive has resulted in immense migration. For example, in the Sierra Zongolica (mountain range near Cordoba) the coffee farmers are directly dependent on the middleman Christian Garey from Cordoba, who pays them only 6.5 pesos/kg and also sells to the AMSA Beneficio in Ixthuatlan. In several villages there are daily buses that bring the impoverished population to Mexico City, hoping to get a better paying job there.

The food company Nestlé dominates whole regions in Mexico and especially in Veracruz and is the main cause of an ever increasing migration. They have new, large Robusta coffee cultivation projects in the coastal region of Veracruz before, which will change the whole structure locally and give themselves thereby innovatively and lastingly. They also presented these goals at the Sustainability Congress of the German Coffee Association on June 5, 2019, ahead of last year’s World Of Coffee WOC coffee fair in Berlin. It was about the Nespresso AAA Fairtrade projects in Colombia, which were presented by project manager Karsten Ranitzsch in a beautiful, picture-rich PowerPoint presentation.

When I asked about Nestlé’s pricing policy in Mexico and the Nespresso project in Veracruz, Mr. Ranitzsch reacted somewhat indignantly. He said literally: “I am not from Nestlé but from Nespresso”! Astonished murmurs filled the room and I could not hide my smile. I asked why there were so many protests and strikes? To which he replied: “Where did you get that”? I then : “From the coffee smallholders organization CNOC”! He answered somewhat effervescent: “I know your articles” whereupon I then said: “Well then you know also the situation locally and the prices” whereupon he broke off and went. The coffee audience was a bit taken aback and the panel was over. This reaction had not surprised me and I took it upon myself to visit these Nestlé AAA Fairtrade flagship projects in Colombia in January/February 2020.

I chose one of the two Nespresso projects because I wanted to visit other projects there near Medellin. So I drove from Bogota via Manizales to Aguadas Caldas to the Cooperativa de Caficultores de Aguadas. The Caldas region is one of the main coffee growing areas in Colombia and one could hardly see the effects of the Roya coffee plague(coffee rust). The Federacion Nacional Cafetalero (FNC) has done an excellent job there, renovating many times the cafetales (coffee growing areas) with the varieties Colombia and Castillo. Thanks to a contact at the University of Medellin, I met producers near Aguadas. The Coop is Fairtrade certified ID 831 and is in the Nestlé AAA program and acts as a bulk buyer in the region for Nestlé. The coffee cooperative price of 850,000 pesos COP ($2.11 USD) per carga of 125 kilos(is set by the FNC. There are also quality differentials, but these can vary widely. The Fairtrade licensed middleman and exporter Expocafe buys from the Coop Aguadas at the minimum Fairtrade price of $1.40 USD / pound + 20 US cents premium/pound, i.e. per kg $2.80 + 40 cents = $3.20 USD /kg. Expocafe in turn sells to Nestlé/Nespresso similar to AMSA in Mexico.

However, the Coop Aguadas paid the producers at the end of January a Nespresso base price per pound of 7,320 COP / (1.05 $ USD) with the AAA allowance then 7,840 COP (1.12 $ USD) a so-called “Farmgate Price”, the price that ultimately the coffee farmers get. This farmgate price is not listed in the Fairtrade FT certification process, but the Free on Board FOB price (the price at the export port) and I had to ask Max Havelaar CH, the fair trade certifier in Switzerland, what they have negotiated with Nestle headquarters in Vevey/Switzerland, because an almost 1/3 deduction for the coffee farmers of about 50 US cents is decidedly too high in fair trade.

Although the cooperative has its own costs such as wages + technology, but the problem is the trazabilidad, traceability, price fixing and the lack of quality differentials at the Coop Aguadas. Although there are additional premiums from Rainforest Alliance and Starbucks Best Practices of about $1.05 USD each, but for now they have nothing to do with the minimum price of Fairtrade. The inquiry with Simon Aebi of Max Havellaar Switzerland resulted in the following answer: “For Farmgate there is no minimum price in the FT-system” and “By the way, for large cooperatives there are no special conditions concerning minimum price and premium”. So it is up to the management of the Coop Aguadas which price they pass on to their members. In this case without quality potential what other FT Coops as for example the Coop Red Ecol Sierra from Santa Marta/Sierra Nevada, which export to Germany to El Puente and Café Libertad, handle completely differently.

There, a triple quality differential is applied and the farmers always get above the FT minimum price of 1.40 USD /pound+20 cents premium without deductions! A producer of the Coop Aguadas formulated it in such a way: “The prices of the Federacion are very dreary, if they had to sell only for the price”.

My subsequent inquiry to Nestlé/Nespresso in Frankfurt/M and Vevey was not answered directly, but with a time delay by their PR agency Weber Shandwick Ms. Bordeloi. She essentially confirmed my research and the statements of FT Max Havelaar CH : “The price of 7,480 pesos/kg you mentioned can be explained in such a way that the Fairtrade minimum price of USD 1.40/lb refers to the free on board (FOB) price. Of this price, on average in Latin America, about 70% (the exact percentage is determined with the respective cooperatives) goes to the farmers, and the remaining 30% is invested in the cooperative for aspects such as administration and infrastructure.” In the case of Coop Aguadas, the deduction is about 63%! The cooperative management of Red Ecol Sierra, with whom I discussed the problem for a longer time, wanted to discuss this “Farmgate Price” problem also at the next Colombian Fairtrade meeting.

But that was all before Covid-19. The Fairtrade Congress on 25.3.2020 in Berlin has also been postponed. There I wanted to bring appropriate questions into the panel. With preliminary inquiries to Transfair Germany I was referred to the congress and/or to Max Havelaar Switzerland.

At the Nespresso project in Aguadas there is a AAA surcharge of 3 US cents, likewise in Ixthuatlan 3 US cents. The explanation of the Nestle agency reads like this: ‘An important aspect is the fair payment of the farmers. As a member of the AAA program, farmers receive a AAA premium from Nespresso, and for additional Fairtrade certified coffee, Nespresso also pays a premium of USD 0.20/lb(pound) to the cooperative, which is used to support social protection initiatives for farmers such as the AAA Farmer Future Program pension fund or climate change insurance’. The 3 US cents were not specifically named.

Let’s go back to Mexico, to Veracruz, where Nestlé is planning a large Robusta coffee cultivation project, including a new factory in the industrial park of the city of Veracruz. A total investment of $200 million U.S., according to their own figures, of which 154 million is in the factory alone. The deal was personally approved and signed by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO for short.

I discussed this with the president of the coffee smallholder organization CNOC, Fernando Celis in Mexico City. He explained the context and the immense expansion of the Robusta Project. A total of 150,000 hectares of new coffee cultivation area are to be created, 80,000 of which in the coastal plain north of Veracruz City. These will replace the existing Robusta coffee imports from Vietnam, Brazil, Indonesia and Ecuador. It is also made easy for the Nestlé Group, because some former managers have now changed to government positions, such as Vicente Roma in the Ministry of Agriculture SADER, Eduard Cadenas in the Ministry of Agriculture Veracruz, Ernesto Faust is now a senator in Veracruz, previously with AMSA. It is also easy to apply for and pass the money of the fund ‘Sembrando Vida’ (sowing life) for the Robusta coffee cultivation, a tax money gift from AMLO, which will provoke even more unemployed farmers and farm workers to move north. The controversial fund was supposed to be for reforestation programs to counter climate change. But the argument is similar to that of palm oil cultivation, because after all, these are green plants and jobs! “This policy of big corporation promotion creates mass migration and unfortunately there will be no remedy,” says Fernando Celis. Yet there are also very good Robusta qualities, such as at Coop Ismam in Chiapas, which grows both organic/Fairtrade highland Arabica and organic/FT Robusta in lower-lying areas and supplies them to World Partners and Gepa in Germany. The average Robusta production price worldwide was $50 U.S. dollars for 100 pounds of green coffee according to OIC Organisation International de Cafe. Equivalently, in Mexico, a quintal (47 kg) pays no more than 900 pesos/$35 USD. Nestlé wants to produce 50 quintals per hectare and do so at the lowest possible production costs with harvesting machinery and little human capital. This will also affect sales of Arabica production in Mexico, which generally requires shade trees and high labor input. A significant drop in prices is to be expected, says Fernando Celis. The consequences are unfortunately already all too clear: mass rural exodus. These consequences were also the topic of discussion at the Specialty Coffee Meeting of SCA Specialty Coffee Association, SADER, Amecafe and other coffee organizations in Mexico City on February 20/21, 2020, where the consequences of the Roya plague crisis and the development of new markets were discussed. Various representatives of the government and coffee organizations cheered up the professional audience with their contributions. There were discussions in working groups and a lot of interesting ideas to move consumer behavior towards more quality. Fair trade and direct trade were of course also a topic and corresponding initiatives were presented, e.g. by Femcafe/Veracruz. Big companies like Nestlé or big traders like AMSA, Rothfos/Neumann- Café California, Olam, Volcafé etc. were not represented.

The Nestlé major project was only a marginal topic, because it has been virulent for years. Only the current Corona Shock could possibly stop it, because coffee sales have already declined noticeably in the last two weeks. Whether it affects the sales of the large corporations in the same way will be seen. In the small roasting plants in this country is now already partly -70% to -80% decline in sales due to closed cafes and restaurants. That means it is not a good outlook at the moment and it would be a good idea to prevent any possible windfall effects, i.e. buyouts of large companies by the monopoly authorities. With regard to the blatant violence situation, there has already been a sharp increase in killings by paramilitaries against opposition members, environmentalists and feminists in Colombia. A very violent Corona effect, unfortunately. This is also the case in Mexico.

Jan Braunholz is a journalist, docfilmer and coffeegrader and works for the NGO Flüchtlingshilfe Mittelamerika e.V.

https://cafe-cortado.tem.li