taken from Blackout

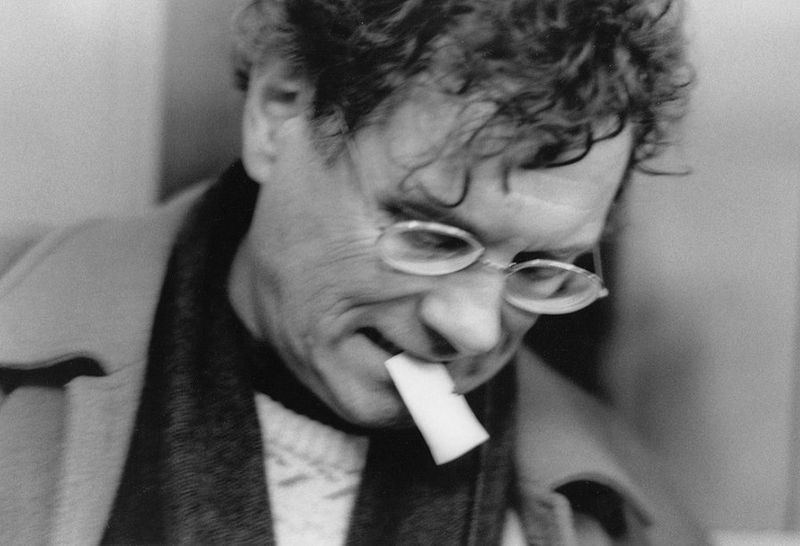

The following discussion with Félix Guattari took place in his

apartment in Paris. With the help of a number of friends, I had prepared

a set of questions, and had contacted him to see if he might be

available to answer some of them.\1 He responded immediately, and left

messages with the friend in Paris in whose apartment I would be staying.

Prior to the trip, I also had contacted Gilles Deleuze to arrange an

extended interview, and although his schedule and health prevented him

from agreeing to a long session, I did visit him at his apartment the

night before the session with Guattari.

I met Guattari in his in the sixth arrondissement

apartment, near the Odeon, and we spent about three hours talking, then

ran errands in the neighborhood, had lunch, and then continued talking

for a few more hours. He was extremely generous with his time, more than

willing to consider anything I threw his way, and as the reader will

note, extremely patient. Shortly after the interview, I realized that I

had overdone the barrage of prepared questions and topics to be treated

and should have limited the subjects to a few that we could have perhaps

considered in greater detail. Also, while preparing this exchange for

distribution and publication, I have winced more than once upon

re-reading some of the question/answer exchanges. Yet, despite having

his patience tried, Guattari spoke entirely without reserve and even

outlined quite extensively some of the elements of his ongoing work.

Although I tried to interest several journals in this interview in

the following years, the its length as well as the notoriously

“difficult” situation of Guattari for many North American critics

combined to make this publication impossible. Only through Internet

contacts on the Deleuze-Guattari List have I seen the demand for a more

thorough and equitable account of Guattari’s contributions to this

collaboration with Deleuze and of his own highly speculative work. A

decade later, some of the topics that we discussed are rather dated, but

I have retained most of these in the text because they do shed light on

Guattari’s thinking, particularly on politics and culture. While I have

also reviewed my translation, I have refrained from “regularizing” it

too completely in order to leave intact as much of the spontaneity of

Guattari’s verbal pyrotechnics as possible.

Toward the end of our talk, the doorbell rang, and while Guattari

answered, I excused myself for a few minutes. When I returned, he

introduced me to a lean, greying man, Toni Negri, whose mail Guattari

was receiving and who had an appointment with Guattari. I took my leave,

and saw Guattari again only once, in 1990 in Baton Rouge at Louisiana

State U, where he presented an edited version of his Les trois écologies (The Three Ecologies). [Charles J. Stivale]

I. Pragmatic

1. “Deleuze-thought”

CS: Referring to the front cover of SubStance 44/45 (1984), once again the name “Gilles Deleuze” blocks out the name of Félix Guattari. This blockage, that quite often occurs when someone refers to the schizoanalytic project, seems to correspond to the effect you emphasized in “Machine and Structure” (Molecular Revolution),\2 the effect of transforming a proper name into a common noun, i.e. erasing the individual. How do you react to these two effects, the blockage of your name and the “figuration” of Gilles Deleuze’s name?

FG: I can’t give you a simple answer because I think that behind this

little phenomenon, there are some contradictory elements. There is a

rather negative aspect which is that some people have considered

Deleuze’s collaboration with me as deforming his philosophical thought

and leading him into analytical and political tracks where he somehow

went astray. So, some people have tried to present this collaboration,

often in some unpleasant ways, as an unfortunate episode in Gilles

Deleuze’s life, and have therefore displayed toward me the infantile

attitude of quite simply denying my existence. Sometimes, one even sees

references to L’Anti-Oedipe or _Mille plateaux in which my name

is quite simply omitted, in which I no longer exist at all.\3 So, let’s

just say that this is one dimension of malice of a political nature.

One could also look at this dimension from another perspective: one

could say, OK, in the long run, “Deleuze” has become a common noun, or

in any case, a common noun not only for him and me, but for a certain

number of people who participate in “Deleuze-thought” (la pensée deleuze)

as we would have said years ago “Mao-thought”. “Deleuze-thought” does

exist; Michel Foucault insisted on that to some extent, in a rather

humorous way, saying that this century would be Deleuzian, and I hope

so.\4 That doesn’t mean that the century will be connected to the

thought of Gilles Deleuze, but will comprise a certain re-assemblage of

theoretical activity vis-a-vis university institutions and power

institutions of all kinds.

CS: What are your current projects, and don’t you have a book which will appear soon on your clinical work?

FG: I have two books which are going to appear, a book with Toni Negri,\5 Les nouveaux espaces de liberté (The New Spaces of Freedom); then, a collection of articles dating from the last three or four years. I thought of calling it Les années d’hiver (The Years of Winter), but I don’t know. Then there is a third collection which will be texts on schizo-analysis.\6

2. Molecular Revolutions in Europe

CS: You spoke to me earlier about the College International de Philosophie,\7 so what are your goals in this activity and your hopes for this institution, and in terms of the schizoanalytic enterprise, how do you understand your participation there?

FG: I warned you ahead of time: I don’t understand it at all now! (Laughter)

CS: Right, you just mentioned that you no longer are involved there, that you no longer belong to the College?

FG: No. The people, not the founders, who have taken control of this institution, sometimes by means that recall more the life within small political groups than a self-respecting, purely scientific activity, the people who thus brought off this operation are not devoid of qualities quite generally, but have a conception of philosophy that, in my opinion, is traditional in its exercise and that therefore does not allow the construction of a new institution since, after all, the way they want to develop philosophical studies could be done entirely in the framework of existing university institutions.

CS: How do they understand philosophy?

FG: Well, you understand, this College de Philosophie, we had the idea, with a certain number of friends, Jean-Pierre Faye in particular, immediately after the arrival of the socialists in France in 1981. The idea was to develop completely new forms of collective reflection, particularly in the field of relationships between science and philosophy, art and philosophy, and for my part, in the domains of reflection about urbanism, education, health and psychiatric questions. It was therefore a conception, let’s say, much closer to that of the Encyclopedists of the 18th century than to university philosophy as it has developed, and in my opinion, as it has dried up philosophy. So, instead of accepting the idea of a multi-polarity entirely necessary for the project as I just defined it, the present team, which took control of the College de Philosophie, created a sole central body that distributes transitory seminars, without much continuity, uniquely directed in the end toward subjects that recall an education in the history of philosophy, obviously with some interesting innovations, of course, but subjects that finally don’t allow one to do anything more than present a complementary teaching. These subjects don’t allow us to undertake or to establish research or “think” teams with people who are not in the university field of philosophy, therefore to develop a mediating or interfacing perspective in completely new ways. So, Jean-Pierre Faye and I were entirely prepared to collaborate with these people devoted to this way of thinking, but provided that they had their precisely delimited territory and didn’t attempt to invade and direct the College de Philosophie like a political bureau with a central committee whose general secretary would direct the so-called philosophical organizations. We have therefore decided to constitute something else, another European college of philosophy, hoping to have the means to realize its development.

CS: Given that you’re considering a European college, what is happening in Europe as far as “molecular revolutions” are concerned? Are there any “molecular revolutions” taking place in Europe or in France?

FG: That’s an interesting and embarrassing question at the same time

because one might think, a lot of people think, that this whole

dimension I called “molecular” — this dimension of interrogation of the

relationship between subjectivity and all kinds of things, the body,

time, work, problems of daily life, all the becomings of subjectivity

addressed by these molecular revolutions –, one might think that it was a

passing phenomenon, connected to events of the ’60s, to the new culture

of the ’60s, a flash in the pan, perhaps a dream, a fantasy, with no

tomorrow. Today [1985], everything seems to have returned to order, and

it’s now the era of the new conservatism, something that you know quite

well in the United States. But, people like me who continue to think

that, on the contrary, this movement continues, whatever the

difficulties and uncertainties might be, we are taken either for

visionaries or completely retro and unhinged. Well, I willingly accept

this aspect, much more willingly than many other things, because

basically . . . I think that, in ’68, not much happened. It was a great

awakening, a huge thunderclap, but not much happened. What has been

important is what occurred afterward, and what hasn’t ceased occurring

ever since. Thus, the molecular revolutions on the order of the

liberation of women have been very important in their scope and results,

and they are continuing across the entire planet. I am thinking to some

extent of what I encountered in Brazil, of the immense struggles of

liberation of women that must be undertaken in the Third World.

There is at present a very profound upheaval of subjectivity in France

developing around the questions of immigrants and of the emergence of

new cultures, of migrant cultures connected to the second generations of

immigrants. This is something that is manifested in paradoxical ways,

such as the most reactionary racism we see developing in France around

the movement of Jean-Marie Le Pen,\8 but also, quite the contrary,

manifested through styles, through young people opening up to another

sensitivity, another relationship with the body, particularly in dance

and music. These also belong to molecular revolutions. There is also a

considerable development, which, in my opinion, has an important future,

around the Green, alternative, ecological, pacifist movements. This is

very evident in Germany, but these movements are developing now in

France, Belgium, Spain, etc.

So, you’ll say to me: but really, what is this catch-all, this huge

washtub in which you are putting these very different and often violent

movements, for example the movements of nationalistic struggles (the

Basques, the Irish, the Corsicans), and then women’s, pacifist

movements, non-violent movements? Isn’t all that a bit incoherent? Well,

I don’t think so because, once again, the molecular revolution is not

something that will constitute a program. It’s something that develops

precisely in the direction of diversity, of a multiplicity of

perspectives, of creating the conditions for the maximum impetus of

processes of singularization. It’s not a question of creating agreement;

on the contrary, the less we agree, the more we create an area, a field

of vitality in different branches of this phylum of molecular

revolution, and the more we reinforce this area. It’s a completely

different logic from the organizational, arborescent logic that we know

in political or union movements. OK, I persist in thinking that there is

indeed a development in the molecular revolution. But then if we don’t

want to make of it a vague global label, there are several questions

that arise; there are two, I’m not going to develop them, I’ll simply

point them out. There is a theoretical question and a practical

question:

1) The theoretical question is that, in order to account for these

correspondences, the “elective affinities” (to use a title from Goethe)

between diverse, sometimes contradictory, even antagonistic movements,

we must forge new analytical instruments, new concepts, because it’s not

the shared trait that counts there, but rather the transversality, the

crossing of abstract machines that constitute a subjectivity and that

are incarnated, that live in very different regions and domains and, I

repeat, that can be contradictory and antagonistic. That is therefore an

entire problematic, an entire analytic, of subjectivity which must be

developed in order to understand, to account for, to plot the map of (cartographier) what these molecular revolutions are.

2) That brings us to the second aspect which is that we cannot be

content with these analogies and affinities; we must also try to

construct a social practice, to construct new modes of intervention,

this time no longer in molecular, but molar relationships, in political

and social power relations, in order to avoid watching the systematic,

recurring defeat that we knew during the ’70s, particularly in Italy

with the enormous rise of repression linked to an event, in itself

repressive, which was the rise of terrorism. Through its methods, its

violence, and its dogmatism, terrorism gives aid to the State repression

which it is fighting. There is a sort of complicity, there again

transversal. So, in this case, we are no longer only on the theoretical

plane, but on the plane of experimentation, of new forms of

interactions, of movement construction that respects the diversity, the

sensitivities, the particularities of interventions, and that is

nonetheless capable of constituting antagonistic machines of struggle to

intervene in power relations.

I really can’t develop much for you on that; this is simply to tell you

that there is at least a beginning of such an experimentation showing

that this is not entirely a dream, not only mere formulae like I tossed

them out ten, fifteen years ago; and this movement, I believe that it’s

the German Greens who are giving us not its model, but its direction,

since the German model is of course not transposable. But it’s true that

the German Greens not only are people whose activity is quite in touch

with daily life, who are concerned with problems relating to children,

education, psychiatry, etc., who are concerned with the environment and

with struggles for peace. They are also people who are now capable of

establishing very important power relations at the heart of German

politics, and who intervene on the Third World front, for example,

having intervened in solidarity with the French Canaques,\9 or who

intervene in Europe to develop similar movements. That interests me

greatly, the multi-functionality of this movement, this departure from

something that is a central apparatus with its program, its political

bureau, with its secretariat. You see, I’ve returned again to the same

terms I used when we were talking about the College de Philosophie.

CS: That is, the Greens seem to work on all strata, on both molar and molecular strata, of the Third World . . .

FG: Right, and on artistic strata and philosophical strata.

3. French Politics under Mitterand

CS: I’d like to continue the discussion in this political direction. You wrote an article last year entitled, “The Left as Processual Passion,”\10 and you spoke about several aspects of the current political scene. I’d like to know how you see this scene, not only from a political perspective, but from an intellectual one as well. For example, in this article, you spoke of Mitterand’s government, and you said, “The socialist politicos settled into the sites of power without any re-examination of the existing institutions”; that Mitterand, “at first, let the different dogmatic tendencies in his government pull in opposing directions, then resigned himself to installing a tumultuous management team whose terminological differences from Reagan’s ‘Chicago Boys’ must not mask the fact that this team is leading us toward the same kinds of aberrations.” Could you develop these comments by explaining the resemblance that you see between Mitterand’s and Reagan’s politics?

FG: It is not exactly a resemblance. There is, let’s say, a

methodological resemblance which is that these are people, whatever

their origins, their education, who have come to think that there was

only one possible political and economic approach, which they deduced

from economic indices, etc., the idea that they could govern on the

basis of the existing and functioning economic axiomatic.

But, very schematically, here is how I see things: current world

capitalism has taken control of the entirety of productive activities

and activities of social life on the whole planet by succeeding in a

double operation, an operation permeating world-wide (de mondialisation)

that consisted in rendering homogeneous the Eastern State capitalistic

countries and then a totally peripheral Third World capitalism in an

identical system of economic markets, thus of economic semiotizations.

This operation has completely reduced the possibilities; i.e. at the

limit, we no longer have the dual relationship between imperialistic

countries and colonized countries. All are at once colonized and

imperialistic in a multi-centering of imperialism. This is quite an

operation, that is, it’s a new alliance between the deep-rooted

capitalism of Western countries and the new capitalisms constituted by

the “nomenclatura” of the Eastern countries and the kinds of

aristocracies in Third World countries. One incident that I’ll point out

to you, which in fact would be entirely superficial, in my opinion, is

lumping together Japanese capitalism with American and European

capitalisms. For I have the impression that we have yet to understand

that it’s a completely different capitalism from the others, that

Japanese capitalism does not function at all on the same bases. I don’t

want to develop this point, but it would be quite interesting to do so.

The other operation of this capitalism is an operation of integration,

i.e. its objective is not an immediate profit, a direct power, but

rather to capture subjectivities from within, if I can use this term.\11

And to do so, what better technique is there to capture subjectivities

than to produce them oneself? It’s like those old science fiction films

with invader themes, the body snatchers; integrated world capitalism

takes the place of the subjectivity, it doesn’t have to mess around with

class struggles, with conflicts: it expropriates the subjectivity

directly because it produces subjectivity itself. It’s quite relaxed

about it; let’s say that this is an ideal which this capitalism

partially attains. How does it do it? By producing subjectivity, i.e. it

produces quite precisely the semiotic chains, the ways of representing

the world to oneself, the forms of sensitivity, the forms of curriculum,

of education, of evolution; it furnishes different age groups,

different categories of the population, with a mode of functioning in

the same way that it would put computer chips in cars, to guarantee

their semiotic functioning.

Yet, with this in mind, this subjectivity is not necessarily uniform,

but rather very differentiated. It is differentiated as a function of

the requirements of production, as a function of racial segregations, as

a function of sexual segregations, as a function of x

differences, because the objective is not to create a universal

subjectivity, but to continue to reproduce something that guarantees

power with a certain number of capitalistic elites that are totally

traditional, as we can witness quite well with Thatcherism and

Reaganism. They aren’t in the process of creating a renewed and

universal humanity, not at all; they want to continue the traditions of

American, Japanese, Russian, etc., aristocracies.

Thus, there is a double movement, of deterritorialization of

subjectivities in an informational and cybernetic direction of

adjacencies of subjectivity in matters of production, but a movement of

reterritorialization of subjectivities in order to assign them to a

place, and especially to keep them in this place and to control them

well, to place them under house arrest, to block their circulation,

their flows. This is the meaning of all the measures leading to

unemployment, to the segregation of entire economic spaces, to racism,

etc.: to keep the population in place. One of the best ways of keeping

them in place would have been to develop politics of guilt such as those

in the great universalist religious communities. But that didn’t work

too well, these politics of interiorization and guilt, which explains

the collapse of theories like psychoanalysis. Now it’s much more a

systemic thought that asserts itself: it’s a matter of creating systemic

poles that guarantee that the functions of desire, functions of rupture

of balance will manifest themselves the least possible. What is the

best procedure? Much better than guilt is systematic endangering: you’re

sitting in a place, you might have a tiny functionary’s job, you might

be a top-level manager; that’s not important. It’s absolutely necessary

that you are convinced that, at any moment, you could be thrown out of

this job. That concerns the non-guarantees of welfare as well as the

super-guarantees of the salaried professions, with their contracts,

perquisites, dachas, etc. From this point of view, it’s the same in

Russia as in the United States. You are not guaranteed; you are not

guaranteed by a connection, by a territory, by a profession, by a

corporation; you are essentially endangered because you depend on this

system which, from one day to the next, as a function of some

requirement of production or simply some requirement of power or social

control, might say to you: now, it’s over. You might have been the

biggest TV star with tens of millions of fans crazy about you, but in

the next instant, all that could end immediately if there were any

dissension that suddenly resulted in your no longer functioning in the

register of functions we agree to promote for the production of

subjectivity. So it’s that kind of instrument, I believe, that gives

this power to integrated world capitalism.

And so, in that case, what does a socialist government do when it comes

to power in France? At the beginning, it thinks that it will be able to

change all of that, it thinks that it will be able to change television,

hierarchical relationships, relationships with immigrants, etc. And

there is astonishment for six months during the grace period. And then,

since it has no antagonistic instrument, no different social practice,

no specific production of subjectivity, since the government is itself

moulded by bureaucratization, by hierarchical spirit, by the segregation

formed by the integrated model of capitalism, necessarily it discovers

with astonishment that it can do nothing, that it is completely the

prisoner of inflation, of mechanisms that render impossible the

development of a production and a social life in such a country

subjugated by the overall machinery of world capitalism. A guy I know

well, sort of a friend, Jack Lang (the Minister of Culture), discovered

this immediately: he made a few harmless statements, that might have

passed totally without notice, at the UNESCO convention that I attended.

Then he found that he had set off an explosion because he had dared to

touch a tiny wire, a tiny wheel of this mechanism of subjectivation. He

dared to say: after all, this American cinema is something that has

taken much too great an importance vis-?-vis the potential Third World

productions. There was a frightening scandal! He had to beat a retreat

because he questioned, like during the Inquisition, he questioned

fundamental dogma relating to this production of subjectivity.

CS: You have said about the socialist government that by committing itself to “an absurd one-upsmanship with the right in the area of security, of austerity and of conservatism,” the left has not contributed “to the assemblage of new collective modes of enunciation.” What collective modes of enunciation did you foresee?

FG: Listen, from 1977 to 1981, a group of friends and I organized a movement, that wasn’t very powerful, but wasn’t entirely negligible either, whose images I have here [FG indicates the different posters on his living room walls], that was called the Free Radio Movement.\12 We developed about a hundred free radio stations, an experimentation, a new mode of expression somewhat similar to what happened in Italy. Before 1981, the Socialists supported us; Francois Mitterand even came to some of our stations, and there was a lawsuit (I lost it, by the way, I lost quite a few). When they came to power, they created a committee on free radios; they undertook the most incredible machinations with their socialist militants, people who aren’t directly venal in terms of money, but who are part of the venality of power, an administrative venality. To speak bluntly, they appointed their buddies, people who knew absolutely nothing about free radios. The result: at the end of two years, all the stations were dead, and all had been invaded, just like the invaders we were talking about, by municipal interests, by private capitalists, by the large newspapers who already had all the power, by other stations, that resulted in their quite simply killing the Free Radio Movement. I think that if a rightist government had remained in place, we would have continued to struggle and to achieve things. It sufficed that the socialists came to power in order to liquidate all that. I’ve given you the example of free radios, but I can give you the example of attempts at pedagogical and educational renovations. They liquidated it all; no, not everything, since there are nonetheless some experimental high schools like Gabriel Cohn-Bendit’s, one of my friends.\13 But after all, one sees clearly today, and I said this directly to Laurent Fabius [then Mitterand’s Prime Minister], that Chevenement is the most conservative Minister of National Education that we have seen during the Fifth Republic. I could go on and on: in the domain of alternatives to psychiatry, there was an incredible offensive of calumny, of destruction of the alternative network through the lawsuit undertaken against Claude Cigala, claiming that he had raped little boys, I don’t know what else. I could make a complete enumeration for all the potentialities; they weren’t enormous, it wasn’t May ’68, but some beginnings, some new kinds of practices, compositions of new attitudes, of new assemblages, of all that have been systematically crushed. Not that the socialists did this voluntarily; they didn’t realize what they were doing, that’s the worst part! They didn’t realize what they were doing!

CS: So, this failure of the left from a political perspective could be extended undoubtedly to the intellectual domain.

FG: Well, there, the failure has been total.

CS: You also said in this article, “A whole soup of supposed ‘new philosophy,’ of ‘post-modernism,’ of ‘social implosion,’ and I could go on, finally ended up by poisoning the atmosphere and by contributing to the discouragement of attempts at political commitment at the heart of the intellectual milieu.”

FG: Well, the socialists weren’t responsible for that; it had begun well before. But it’s true that despite the sometimes considerable efforts by the Ministry of Culture, the result is quite nil in all domains. For example, in the domain of cinema, French cinema is alive from an economic point of view, but it doesn’t at all have the richness of German cinema or other kinds because in this domain as well, the assemblages of enunciations remained entirely traditional, in the publishing houses, in the classical systems of production, etc.

CS: And your work in change International?\14

FG: They helped us a bit, at the beginning, and then they dropped us. This was, in my opinion, a very interesting and very promising undertaking, but we didn’t have the resources, and as you know, for a journal with that kind of ambition, one has to have resources.

CS: So it no longer exists?

FG: No. Well, there is an issue coming out, we’re still going to put out one or two issues, but what we wanted to create was a powerful monthly, international journal. Instead, the socialists spent billions to support stupidities like the Nouvelles litteraires journal. And I mean billions! It’s shameful.

4. Deleuze-Guattari and Psychoanalysis

CS: Regarding the current intellectual scene, in a recent issue of Magazine littéraire (June 1983), D.A. Grisoni claimed that Mille plateaux proves that “the desiring vein” has disappeared . . .

FG: Yeh, I saw that! (Laughter)

CS: . . . and he called Deleuze “dried up”.\15 What do you think of this? What is your conception of the schizoanalytic enterprise right now, and what aspects of the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia appear to you as the most valid?

FG: They’re not valid at all! Me, I don’t know, I don’t care! It’s not my problem! It’s however you want it, whatever use you want to make of it. Right now, I’m working, Deleuze is working a lot. I’m working with a group of friends on the possible directions of schizoanalysis; yes, I’m theorizing in my own way. If people don’t care about it, that’s their business; but I don’t care either, so that works out well.

CS: That’s precisely what Deleuze said yesterday evening: I understand quite well that people don’t care about my work because I don’t care about theirs either.

FG: Right, so there’s no problem. You see, we didn’t even discuss it, but we had the same answer! (Laughter)

CS: Deleuze and I spoke briefly about the book by Jean-Paul Aron, Les Modernes.\16 What astounded me was that despite his way of presenting things, he really liked Anti-Oedipus. What particularly struck me in his statement about Anti-Oedipus was that “despite a few bites, the doctor (Lacan) is the sacred precursor of schizoanalysis and of the hyper-sophisticated industry of desiring machines” (285). A question that one asks in reading Anti-Oedipus is what is the place of Lacanian psychoanalysis in the schizoanalytic project. One gets the impression that you distance yourselves from most of the thinkers presented, but that Lacan has a rather privileged place to the extent that there is no rupture.

FG: In my opinion, what you are saying is not completely accurate because it’s true in the beginning of Anti-Oedipus, and then if you look, en route, it’s less and less true because, obviously, we didn’t write at the end the same way as we did in the beginning, and then it’s not true at all throughout A Thousand Plateaus, there, it’s all over. This means the following: Deleuze never took Lacan seriously at all, but for me, that was very important. It’s true that I’ve gone through a whole process of clarification, which didn’t occur quickly, and I haven’t finally measured, dare I say it, the superficial character of Lacan. That will seem funny, but in the end, I think that’s how Deleuze and Foucault … I remember certain conversations of that period, and I realize that they considered all that as rather simplistic, superficial. That seems funny because it’s such a sophisticated, complicated language.? So, I’m nearly forced to make personal confidences about this because, if I don’t, this won’t be clear. What was important for me with Lacan is that it was an event in my life, an event to meet this totally bizarre, extraordinary guy with extraordinary, crazy even, acting talent, with an astounding cultural background. I was a student at the Sorbonne, I was bored shitless in courses with Lagache, Szazo, I don’t remember who, and then I went to Lacan’s seminar. I have to say that it represented an entirely unforeseen richness and inventiveness in the university. That’s what Lacan was; he was above all a guy with guts; you can say all you want about Lacan, but you can’t say the contrary, he had no lack of guts. He possessed a depth of freedom that he inherited from a rather blessed period, I have to say, the period before the war, the period of surrealism, a period with a kind of gratuitous violence. One thinks of Gide’s Lafcadio. He had a dadaist humor, a violence at the same time, a cruelty; he was a very cruel guy, Lacan, very harsh. As for Deleuze, it wasn’t the same because he acquired this freedom vis-a-vis concepts, this kind of sovereign distance in his work. Deleuze was never a follower of anyone, it seems to me, or of nearly anyone. I wasn’t in the same kind of work, and it was important for me to have a model of rupture, if I can call it that, all the more so since I was involved in extreme leftist organizations, but still traditionalist from many perspectives. There was all the weight of Sartre’s thought, of Marxist thought, creating a whole environment that it wasn’t easy to eliminate. So, I think that’s what Lacan was. Moreover, it’s certain that his reading of Freud opened possibilities for me to cross through and into different ways of thinking. It’s only recently that I have discovered to what extent he read Freud entirely in bad faith. In other words, he really just made anything he wanted out of Freud because, if one really reads Freud, one realizes that it has very little to do with Lacanism. (Laughter)

CS: Could you specify in which writings or essays Lacan seems to read this way?

FG: The whole Lacanian extrapolation about the signifier, in my opinion, is absolutely un-Freudian, because Freud’s way of constructing categories relating to the primary processes was also a way of making their cartography that, in my opinion, was much closer to schizoanalysis, i.e. much closer to a sometimes nearly delirious development — why not? — in order to account for how the dream and how phobia function, etc. There is a Freudian creativity that is much closer to theater, to myth, to the dream, and which has little to do with this structuralist, systemic, mathematizing, I don’t know how to say it, this mathemic thought of Lacan. First of all, the greatest difference, there as well, is at the level of the enunciation considered in its globality. Freud and his Freudian contemporaries wrote something, wrote monographies. Then, in the history of psychoanalysis, and notably in this kind of structuralist vacillation, there are no monographies. It’s a meta-meta-meta-theorization; they speak about textual exegesis in the _n_th degree, and one always returns to the original monography, little Hans, Schreber, the Wolf Man, the Rat Man.\17 So all that is ridiculous. It’s as if we had the Bible, the Bible according to Schreber, the Bible according to Dora. This is interesting, this comparison could be pushed quite far. I think that there is the invention of the modelization of subjectivity, an order of this invention of subjectivity that was that of the apostles: it comes, it goes, but I mean that it’s moving much more quickly now than at that time, i.e. we won’t have to wait two thousand years to put that religion in question, it seems to me.

CS: It also seems to me that there are many more apostles who have betrayed their master than apostles who betrayed Jesus.

FG: I was thinking more of the apostles, I see them more as Freud’s first psychoanalyses; then, it’s the Church fathers who are the traitors. Understand, with the apostles, there is something magnificent in Freud, he’s like a guy who has fallen hopelessly in love with his patients, without realizing it, more or less; a guy who introduced some very heterodoxical practices, nearly incestuous when you think of what was the spirit of medicine at that period. So, he had an emotion, there was a Freudian event of creation, an entirely original Freudian scene, and all that has been completely buried by exegesis, by the Freudian religions.

CS: A few minutes ago, you mentioned Foucault. I asked Deleuze this question about Foucault yesterday evening: what are your thoughts on Foucault nearly a year after his death? How do you react to this absence, and can we yet judge the importance of Foucault’s work?

FG: It’s difficult for me to respond because, quite the contrary to Deleuze, I was never influenced by Foucault’s work. It interested me, of course, but it was never of great importance. I can’t judge it. Quite possibly, it will have a great impact in different fields.\18m

CS: Deleuze told me something very interesting: he said that Foucault’s presence kept imbeciles from speaking too loudly, and that if Foucault didn’t exactly block all aberrations, he nonetheless blocked imbeciles, and now the imbeciles will be unleashed. And, in terms of Aron’s book, Les Modernes, he said that this book wouldn’t have been possible while Foucault was alive, that no one would have dared publish it.

FG: Oh, you think so?

CS: I really don’t know, but in any case, when it’s a matter of machinations on the right . . .

FG: It’s certain that Foucault had a very important authority and impact.

5. The Americanization of Europe

CS: There’s another question I want to return to. In terms of capitalism in the world, I’d like to consider the question of the Americanization that penetrates everywhere, for example, the “Dallas” effect. There is even a French “Dallas”, “Chateauvallon” . . .

FG: It’s not bad either. It’s better than “Dallas,” I find.

CS: Of course, for the French. But when you like J.R. . . .

FG: That’s true. J.R. is a great character, quite formidable.

CS: But what strikes me in your writing, especially in Rhizome,\19 is the impression of a kind of romanticism about America, references to the American nomadism, the country of continuous displacement, deterritorialization . . .

FG: Burroughs, Ginsberg . . .

CS: Right, and one gets the impression of a special America, and we Americans who read your texts, we know our America, and here in France, as a tourist this time, I see the changes, the penetration of our culture that has occurred over the last few years, the plastification, the fast food restaurants everywhere . . .

FG: Ah, it’s incredible. And in the popular social strata, among the youth, they babble this kind of slang, they’ve completely identified with it, it’s incredible. It’s all over Europe, everywhere, the linguistic phenomenon of the incorporation of American rock. It’s really surprising.

CS: So there are two conceptions of America: this nomadic conception which you present in your works, but that is finally a romantic conception in light of the practice of Americanization, the penetration of America and, of course, of capitalism. It seems that one does not go with the other, so how do you explain this difference? It’s not really a contradiction, but simply a distance between two conceptions of America.

FG: Well, that’s complicated. I’m not very clear about that because .

. . I went to America occasionally, especially during the ’70s, and

then afterwards, during the ’80s, I’ve gone to Japan, to Brazil, and to

Mexico a lot, and I’ve no longer wanted to go to the United States. I

haven’t considered it well, I haven’t understood why.

You know, it’s not certain that this is a romantic vision. Americans are

often jerks; they have a pragmatic relationship with things; they are

dumb, and sometimes, this is great because they don’t have any

background as compared to Europeans, Italians, but there is an American

functionalism that makes us pass into this a-signifying register, that

transports a fabulous creationism, fabulous anyhow in the

technical-scientific domain, because they are really a scientific

people; they don’t look for complications, it works or it doesn’t, they

move on to something else.

I met an American last summer, I was in California, at Stanford, I don’t

know where. I was on a tour to study the problems of mental health, a

mission for the Ministry of Exterior Affairs. Americans are people who

receive you very well, who take time to talk, which isn’t the case here,

not the same kind of welcome. So, each person that I met gave me an

hour for discussion, and there, this young psychiatrist explained what

had happened after the Kennedy Act, the liquidation of the big

psychiatric hospitals and the establishment in his sector of half-way

houses, a kind of day hospital to replace the big hospitals. He made a

diagram chart, I remember, there was a graph with double entries, there

were all the dimensions of these establishments, a remarkable

organization of what had been developed. So, he finished presenting all

that to me, and then the conversation finally ended, but there still

remained ten minutes because we had an hour for our discussion, so there

was no reason to leave. And I asked him a final question: “And so, how

did all that work? What was the result?” He broke out laughing: “Nil.

Zero. It didn’t work at all!” I said: “Oh, really?” He said: “Yes, it’s

just a program we made, but it didn’t work at all!” That was like a

thunderbolt for me that this guy had made this entire development, and

then it didn’t work, so let’s do something else. We see this well in

Bateson’s work: he makes a program on something, it works, but that

doesn’t matter, they move on to something else because they were on

contract.\20 That’s what I find to be the marvelous a-signifying

freedom, going on to something else, going on to something else. They

massacre Vietnamese for years, then afterwards, oh, well, no, that was

stupid, let’s go on to something else.

So I wonder if that isn’t the rather invading, yankee side of Americans

that makes us ask what they’re up to, what they’re looking for. But one

shouldn’t try too hard to discover what they’re looking for or what

they’re up to. It’s the same for the Japanese, but with an entire

background of mysticism, of religiosity, that also exists in the United

States, but without being structured the same way.

CS: But where could we insert this question of nomadism? We have this “go on to something else” nomadism, so perhaps that’s it, Kerouac, going on to something else . . .

FG: And next, and next, and next, constantly, constantly, and now, and now.

CS: . . . but his kind of incessant deterritorialization only exists in extreme cases, so to speak.

FG: But, no, that’s not true. Jean-Paul Sartre, when he made his trip to America — that must have been in 1947 or thereabouts — wrote a magnificent article about American cities. He explained that American cities aren’t cities in the European sense, i.e. they have no contours. They are crisscrossed by avenues, they have no limit. In my terminology, this means that these are deterritorialized cities. America is entirely deterritorialized. “Deterritorialized” means that instead of having obstacles or having land, things, curves, there are lines, trains, planes, everything crossing, everything sliding, demographic flows sliding everywhere, and on top of that, there are extraordinary reterritorializations. Henry Miller in Brooklyn, Faulkner in a certain sense, because for Faulkner, to what extent isn’t it a misreading to situate him as an archaic writer of American life? Isn’t he rather a mythical reterritorialization about deterritorialized America? We’d need to debate that; I’m not able to undertake it about Faulkner. Anyway, how does one make oneself a body without organs, how does one make oneself a little territory, a life, a warmth, a childhood, in this American mess, in this whole mishmash spread out all over? Look at the extraordinary poetry of shop windows in New York! You know the shop windows in France or in Italy. But there, in New York, most of the windows speak, even on the main streets where you have side by side expensive windows and then places where you find piles of any old thing; one finds there a kind of accumulation of vistas like that, where there are marvelously beautiful things from an architectural perspective, and then there is a dump, a maximum and then a mess.

CS: I do understand the difference between cities, the constant sliding across territorialities between city and suburb. But quite simply, this invasion, the body snatchers, America as body snatcher, the grip of capitalism in other countries, for me . . . well, perhaps that all belongs to the same process of deterritorialization: there is no territory, either in individual existence or in capitalistic flows: they invade everything, everywhere, everybody, everywhere in the world, without limits, without borders, crossing and invading France.

FG: But don’t you think that this deterritorialization, catastrophic from many perspectives, is precisely the occasion for extraordinary reterritorializations? That is, it’s difficult to make oneself a territory on the moon, really; it’s more complicated than going out to the French countryside. America is a bit like the moon, it’s very complicated, and precisely these traits create a difference from the Japanese as well because the Japanese have means of reterritorialization, a very ancient civilization, they have insignia, emblems of this reterritorialization, corporal techniques, etc. Whereas there, in America, they are forced to re-invent everything, these kinds of continental Galeries Lafayette, anything. So that becomes a formidable exercise: to create music with a tradition of religious music is difficult, but creating music with just anything, like that, with these piles of metal, it’s something else altogether. And when they succeed, it’s fantastic. But look: take the American mystery novel whose basic material is all this deterritorializing trivia, and look at what warmth of intimacy, of suspense, of subjectivity that you grab to stay warm, to sleep, to feel good, to feel sheltered; it’s really something. With what do they create that? What are they talking about? These aren’t tales of chivalry. American cinema as well has a lot of that: look at the power of American culture to produce a more than tolerable and comfortable subjectivity, warm, passionate, exciting, in this pile of metal, this heap of shit, this load of stupidities, as I said earlier. Isn’t that really quite a feat? It’s nonetheless a civilization that has created some extraordinary forms of subjectivation. Jazz … do you realize? Jazz has a great impact on the level of world culture. Line up cinema, jazz, the mystery novel. I’ll leave painting aside because I find that, in the long run, it’s not a very noticeable success because it really belongs to capitalistic deterritorialization, seriously, with some exceptions, but for me, it’s really a lot less convincing.

CS: I think that the problem for me is that I’m too close to daily life in the States, and I see so much stupidity in all these areas. In cinema, one constantly sees exploitation of the body, of the individual. In music, there is so much shit . . .

FG: That’s true; when one hears the classical music that people listen to in the United States, it’s overwhelming. Won’t you ever get fed up with Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, and all that . . .?

CS: I was really thinking about popular music, where all that might happen, where changes did occur during the ’70s. But what always strikes me is that the music comes from England to invade America, and then America reterritorializes what the English do, and they lose everything. That began with the colonies and continues today. But, perhaps its my own problem, being too close to this daily life, and not being able to see this abstract machine which you are outlining. But, on the other hand, the reproach made by friends who read A Thousand Plateaus and other works is really that in regards to American nomadism, this deterritorialization, they’d like to believe in it, but isn’t the general schizoanalytic enterprise in the long run a utopic dream without any future?

FG: I’m sorry to interrupt you, but in any case, the idea of a utopic dream just doesn’t hold water. A dream is necessarily utopic, in any case. We participated a little in that America, that kind of New West. It was our dream, our very own America. You are telling me that it’s not yours! I find that fascinating, but you aren’t going to reproach me for having dreamt my dream! You have a whole generation of American writers who created a dream about Europe, about Greece, who landed here like these were colonies, but I’m not going to reproach them for having perceived in their own way, “what is this Europe you saw here?”, that’s just not possible! What one has to know is: has it been useful for you that we had that dream? has it been useful for us that you had that dream, that some American writers had a particular dream about Europe before the war? For me, yes, that certainly was useful. I haven’t looked at Europe in the same way because there is this deterritorialized vision by relay from American writers. Miller’s vision of Paris, for me, is enormous, is fundamental! I’m sorry that Deleuze and Guattari’s vision of the United States hasn’t been at all useful for you, but we can’t all have the same talent as Miller! (Laughter)

6. Left and Right Readings of Deleuze-Guattari

CS: That’s not at all what I said, but it’s a question that comes from a friend who is working on Anti-Oedipus and is waiting for the translation of Mille plateaux . He is trying to use the developments of schizoanalysis in his work on the philosophy of communication, how effects of communication are produced on sociological as well as philosophical levels. So, he is attempting to present this thought, and his students, from another generation of thinkers, reveal a certain cynicism that dominates all Western societies, not only in the United States, but a cynicism that sees Marxism, or any thought attempting to outline a theory and a practice, merely as being a utopic dream finally leading nowhere.

FG: But that all belongs to the same reactionary stupidity, it’s the Restoration, the great Restoration. That’s not really important because other generations will soon discover, will soon say, “Oh, that’s right . . .” That’s the dregs of history, it’s valueless. But that still doesn’t prove that there isn’t a potential America, an America of nomadism. Some people still exist . . . I was thinking of Julian Beck, of Judith Molina, the former members of the Living Theater. Just because they’ve been completely marginalized is no reason to ignore their existence. They still exist nonetheless.

CS: There’s another reproach made about Anti-Oedipus, and you might lump it together with the previous objection, regarding a kind of recuperation of schizoanalytic thought by the right. There was recently an article in Le Nouvel Observateur,\21 an article about a book by Michel Noir, 1988. Le grand rendez-vous, where he uses Mille plateaux and a book by Prigogine as the organizing model for a new rightist thought.

FG: Oh, really? I didn’t know about it. Do you have it there?

CS: Yes. [Guattari peruses the article] So here are two kinds of reproach: in the States, some people think that here is a thought that merely boils down to a utopic dream, and others say, right, but this schizoanalysis is a thought without any ideological specificity, if you will; that is, either the left or the right can make use of it. It’s this question of the tool box: a little earlier, when I questioned you about the use of schizoanalysis, you said, yes, in the end, I continue to work, and what people do with schizoanalysis doesn’t interest me, they can take it or leave it, but I’m busy with our work. That’s all well and good, but here is French neo-liberalism, a rightist intellectual using it. Still again, that may not matter at all to you…

FG: Oh, not at all because what does it mean to attach a name like that, to hook our names onto it as a reference? Is it true, does it correspond to anything? It’s quite simply a paradox. And then there is another aspect of this thing: this left-right split is absolutely evident in social struggles, in power relations, as shown in the current reactionary upheaval, the rise of racism. But on the level of thought, it’s not at all clear. Let’s take a very simple example, the example of schools: I’m for free schools,\22 not free schools run by priests, but I’m for the liberation of schools, I’m in favor of dismantling national education, etc. So, is this a theme of the right or the left? A while ago, Gerard Soulier, a law professor who organized a prisoners’ review on culture in prisons, did a study on drugs, and he quoted me as explaining that I was for the elimination of all repression of the spread of drugs since that was the best way to avoid an escalation of dealers, of criminality, etc., and right beside this, he placed an identical statement word for word from Milton Friedman! Understand?

Notes [for section 1, “Pragmatic”]

\1 For helping me formulate many of the questions examined in this discussion, I must thank Jack Amariglio, Serge Bokobza, Rosi Braidotti, Peter Canning, Stanley Gray, Lawrence Grossberg, Alice Jardine, Charles D. Leayman, Vincent Leitch, Stamos Metzidakis, and Paul Patton. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Committee on Grants of Franklin and Marshall College for the research support which it awarded me for this interview project.

\2 The issue of SubStance in question that I guest-edited, entitled “Gilles Deleuze”, includes articles that discuss works by Deleuze and Guattari, particularly Mille plateaux. The collection of translated essays, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics, trans. Rosemary Sheed (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), is a selection of Guattari’s essays first published in Psychanalyse et transversalité (Paris: Maspero, 1972) and La Révolution moléculaire (Fontenay-sous-Bois: Recherches, 1977). For an overview of Guattari’s works in light of this translation, see Charles J. Stivale, “The Machine at the Heart of Desire: Fe’lix Guattari’s Molecular Revolution,” Works and Days 4 (1984): 63-85.

\3 L’Anti-Oedipe: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie, I (Paris: Minuit, 1972), published in English as Anti-Oedipus, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane (New York: Viking, 1977; Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1983), henceforth abbreviated AO; Mille plateaux: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie, II (Paris: Minuit, 1980), published in English as A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987), henceforth abbreviated ATP.

\4 Michel Foucault, “Theatrum Philosophicum,” Critique 282 (November 1970), 885, trans. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1977) 165-196.

\5 With Toni Negri, Les Nouveaux espaces de liberté (Paris: Dominique Bedou, 1985); Communists Like Us, trans. Michael Ryan (New York: Semiotext(e), 1990), that includes an original “Postscript, 1990” by Toni Negri (but omits Guattari’s “Des libertés en Europe” (On Freedoms in Europe) and Negri’s “Lettre archéologique” (Archeological Letter) to Guattari. Antonio Negri is the Italian intellectual accused of complicity in the Aldo Moro affair and of being the chief of the Red Brigade. Jailed under preventive detention in 1979, Negri was freed after four and one-half years in prison thanks to a vote by Italian electors. However, Negri’s immunity was subsequently revoked by the Italian Congress, and at the time of the interview, he was a fugitive living in exile. See “Italy: Autonomia,” Semiotext(e) 3.3 (1980), and Negri’s “Un philosophe en permission,” change International 1 (1983):62-64.

\6 Les années d’hiver, 1980-1985 (Paris: Bernard Berrault, 1986). The “third collection” is no doubt Cartographies schizoanalytiques (Paris: Galilée, 1989), abbreviated henceforth Cs.

\7 For a discussion of the foundation of this College, see Steven Ungar, “Philosophy after Philosophy: Debate and Reform in France Since 1968,” enclitic 8.1/2 (1984): 13-26.

\8 Le Pen is the leader of the French National Front party.

\9 The “Canaques” are the native residents of the French colony of New Caledonia who were seeking the independence promised by Francois Mitterand during his 1981 electoral campaign.

\10 “La Gauche comme passion processuelle,” La Quinzaine littéraire 422 (1 August 1984), p.4 (my translation); reprinted in Les anne’es d’hiver 51-54.

\11 See ATP ch.13, “7000 B.C. – Apparatus of Capture” for further development of this concept; on “cartographies of subjectivity,” see Cartographies schizoanalytiques 47-52, and “on the production of subjectivity,” see Chaosmose (Paris: Galilée, 1992) 11-52. A slightly modified version of Chaosmose’s second chapter has been published as “Machinic Heterogenesis,” trans. James Creech, in _Rethinking Technologies, ed. Verena Andermatt Conley (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1992) 13-27.

\12 For an introduction to the relationship between this political activity and the Italian “autonomia” movement, see “Italy: Autonomia,” Semiotext(e) 3.3 (1980).

\13 Brother of Danny “The Red” Cohn-Bendit. See Susan Brownmiller’s “Danny the Red Is a Green,” Village Voice (June 4, 1985): 1-22.

\14 Guattari was a member of the editorial group of this renewed version of the earlier journal, Change.

\15 D.-A. Grisoni, “La Philosophie comme Enfer,” Magazine littéraire 196 (June 1983):78.

\16 Jean-Paul Aron, Les Modernes (Paris: Gallimard, 1984). Touted as a collection of memoirs “to do away with the master-thinkers” (pour en finir avec les maitres `a penser), this book contains several vicious attacks on various French intellectual figures.

\17 See AO ch.2, “Psychoanalysis and Familialism: The Holy Family”, and ATP ch.2, “1914 – One or Several Wolves?”.

\18 However, only two months later, in May 1985, Guattari would present an address in homage of Foucault at a Milan conference. Published in Les années d’hiver as “Microphysique des pouvoirs, micropolitique des désirs” (207-222), the essay begins: “Having had the privilege of seeing Michel Foucault adapt a formula that I had thrown out rather provocatively, stating that concepts are, after all, only tools and that theories are the equivalent of tool boxes containing them — their power hardly surpassing the services that they render in specific fields and within inevitably circumscribed historical sequences –, you won’t be surprised to see me dig today inside the conceptual array that he has bequeathed to us, in order to borrow from him certain instruments and, if need be, to adapt their use for my own purposes. I am convinced, in any case, that it was always in this manner that he understood how we would manage his contribution” (207-08).

\19 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Rhizome: introduction (Paris: Minuit, 1976), ATP’s introductory chapter, as “Introduction: rhizome.”

\20 Deleuze and Guattari derive the concept of “plateau” from Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind (New York: Ballantine, 1972) 113; cf. ATP 6-7, 158.

\21 Gilles Anquetil, “Dernier Cri du Pret-`a-Penser: Le Néolibéralisme,” Le Nouvel Observateur, 1032 (17 August, 1984). My thanks to Alice Jardine for pointing out this reference.

\22 In other words, Guattari supported an experimental, Summerhill-like approach to education as opposed to the hierarchized, State-supported system in the lay (or l’ecole libre) domain.

II. Machinic

1. “Minor literature”

CS: You have often referred to works by particular American authors as forms of deterritorialization, and I’d like to situate these reflections in relation to what you’ve said about “minor literature” (littérature mineure).\23 Specifically, when you speak of one or several “minor literature(s)”, are these necessarily forms of deterritorialization, and if so, how?

FG: In Kafka’s writing, this kind of deterritorialization of language

is obvious. That is, his work is located on an edge, a border, at the

limit of a huge aggregate in order to deterritorialize, a way of

fighting a kind of “en-sobering”, of making sober, an active return to

sobriety of language. One finds this process of deterritorialization,

for example, in Samuel Beckett’s works, an impoverishment that at the

same time is a placing into intensity, an intensification of expression.

So, I hadn’t thought about it, but in fact, one could make an equation

by saying that whenever a marginality, a minority, becomes active, takes

the word power (puissance de verbe), transforms itself into

becoming, and not merely submitting to it, identical with its condition,

but in active, processual becoming, it engenders a singular trajectory

that is necessarily deterritorializing because, precisely, it’s a

minority that begins to subvert a majority, a consensus, a great

aggregate. As long as a minority, a cloud, is on a border, a limit, an

exteriority of a great whole, it’s something that is rejected, something

that is, by definition, marginalized. But here, this point, this

object, begins to proliferate, to use categories suggested by Prigogine

and Stengers,\24 begins to amplify, to recompose something that is no

longer a totality, but that makes a former totality shift, detotalizes,

deterritorializes an entity.

For example, to return to what we were saying earlier about the German

Greens, one could say that this is more or less what seems to be

produced: a few marginals, whom everybody made fun of, created an

eruption in Parliament, and became representatives. They behave totally

differently, for example, they have a rotation system, they change every

two years, which makes quite a mess in the German or European

Parliaments. And one realizes that the issues they are developing, that

were marginal issues, are becoming not major issues, but issues that

upset the whole society, not only their ecological theme because, in

fact, people realize that the German forests are devastated, and that

the Greens have been announcing it for twenty years; but also because

these are attitudes that question the regular hierarchy, the orders of

value, etc., and this is what I call the process of singularization:

what was ranked as being ordered, coordinated, referenced, now one no

longer knows: what is the face, what are they doing, what is the

reference. The system of values is inverted.

I lived that myself during May ’68. I had the impression sometimes of

walking on the ceiling, of not knowing any more what was going on, when I

found myself in the occupied areas of the Sorbonne where I had been a

student, where I had been completely bored, the amphitheater Richelieu

invaded by students writing graffiti everywhere. What was the order of

the referenced, of the organized, of the coordinated is located in the

order of process because, suddenly, there are singular elements that

quit their enclosure, their singularity, their isolation and begin to be

a kind of exploratory probe, a producing probe, precisely engendering

systems of auto-reference. Instead of being referenced, they are

producers of new types of reference, they are themselves their own

referential until the moment when they are rearticulated,

re-coordinated.

CS: So, this idea of “minor literature” is an auto-production, the production of new territories. And the question one asks is why you limit your examples, you and Deleuze, to reference points in the twentieth century? Aren’t there writers in previous centuries who can also reveal these kinds of deterritorialization?

FG: Yes, certainly. It’s a problem of familiarity. It’s a little difficult because . . . I may be saying something stupid, but it seems to me that the examples of eruption of “becoming-minor” either have been completely buried, or have taken on considerable importance. For example, Jean-Jacques Rousseau could have been a minor writer, but on the contrary, he has a fantastic importance (as perhaps Artaud will have tomorrow), being classified as a principal writer of the twentieth century. I even think this is presently taking place. So, I don’t know. One really has to see the “minor” a bit in its nascent state, one has to see it a bit closer to oneself because the historically distant “minor” has perhaps a different impact. I don’t know, I haven’t thought about this question.

2. _A Thousand Plateaus_: A “speculative cartography”

[FG’s answers to the following sets of questions correspond to the various schema that he was preparing in the mid-/late 1980s for his seminars and, eventually, for publication in Cartographies schizoanalytiques (abbreviated Cs), neither of which I had access to at the time. In revising the text below, I attempt to clarify the dense conceptual terrain, to the extent possible, with reference to Cs.]\25

CS: I’d like to ask several questions going into some detail about ATP. Referring to two terms, “faciality” (the subject of plateau 7, “Year Zero -Faciality”), and another term, “heccéite’” (introduced in plateau 10, “1730 – Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible…”), could you explain what place these concepts hold in rhizoanalysis and to what regimes of signs they correspond? For example, what is the relationship of “faciality” with “black holes”, and what is the function of “haecceity” in the cartographic process?

FG: Oh, la la. That’s enormous. I’d really have to develop a very

complex overview. We need to consider a separate speculative

cartography, divided between two logics: a cardologic, i.e. the logic of

discursive aggregates, and an ordologic, the logic of bodies without

organs.\26

Under the first logic, there are discursive systems, there is always an

aggregate to connect to another aggregate, it engenders a meaning

effect, that can refer you to another meaning effect, creating a double

articulation. There is the arbitrary nature of the relationship: for

example, one might be a phonological chain and the other the semantic

content, but the double articulation can be triple because there is no

primacy of the double articulation. But, each time that there are these

deep structures of meaning, there are also what I call primary modules

of enunciation that then correspond to an ordological aggregate, i.e.

they aren’t discursive. With this in mind, they nonetheless compose

subjective agglomerations as well, agglomerates, constellations, but

that do not accede to expression in the direction of discursive

differentiation, but that emerge in a phenomenon of counter-meaning,

which at one moment is a statement (e’nonce’), for example, the

dream — by the way, I’m going to do an analysis of the dream from this

perspective\27 –which is caught in paradigmatic coordinates, in

energetic coordinates; it (the statement) also serves in the other

direction as enunciator (énonciateur).

So let’s say that there is triple division (tripartition) of

the referential or auto-referential activity of enunciation that goes in

the direction of the discursivity-logic (the cardologic) such that one

can bracket, completely set aside the problematic of enunciation. But

where the problematic reappears is when a statement functions as

organizer of the enunciation; in that case, it’s according to completely

different logical norms because the statement functions to agglomerate,

to juxtapose primary enunciators (under the ordologic). It’s in this

way that we see the double impact of a statement that can work, function

both in the direction of discursive aggregates and in the direction of

what I call “synapses.”

So, we can divide a graph into four categories: the categories of

material, signaletic Flows and of machinic Phyla (under the cardologic),

and the categories of existential Territories and of a-corporal

Universes (under the ordologic).\28 The a-corporal Universes would be

precisely everything that becomes detached from this primary

enunciation, all the pseudo-deep structures of enunciation because here

(under the ordologic) everything is flat, whereas (under the cardologic)

there are effectively deep structures with all kinds of paradigms that

intersect.\29 So, when all the coordinates are unified, these are

capitalistic coordinates; if not unified, these are what one can call

regional or local coordinates.\30

All this is to tell you that with “faciality,” you have a face there

(under the machinic phylum, in the synapses), a face that can be

situated in different coordinates, it’s big, it’s small, it’s white,

it’s like this or that; one can put it in all the paradigmatic

coordinates. One can make a content analysis: what is that face? But

certain traits of this face can be detached from this cardology and

function in the ordological logic, and then it’s the father’s

superego-ish mustache, the grimace, or the gaze of Christ looking at

you, and that then is a discursive chain, but that doesn’t function in

those cardological coordinates, but functions to put on a mask, to

coagulate, to constellate, some subjective enunciators. It’s a bit in

the general lineage of the Lacanian object small-a, it’s a generalized

function of the object small-c or transitional object.\31 It’s this kind

of object that one finds in dreams, in fantasms, in delirium, or in

religion. It’s an object that functions on two registers: in one

register, let’s say, of an aesthetic unconscious because we can say that

it has an aesthetic unconscious, and in a machinic unconscious. So, the

haecceity is the fact that it occurs as an event, but when it emerges,

it has always-already been there, it is always everywhere. It’s like the

smile of the Cheshire cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice, it’s everywhere, in

the entire universe.\32

So there remains a paradox to consider, this logic of the event that is

dated, situated, articulated by a particular use, a sign-function. But

the sign has this double import, that’s why a few years ago — this is

another theme — I preferred to talk about a “point-sign” entity, because

it’s a sign in so far as being a surplus-value of meaning that emerges

from this relationship of repetition. But it begins to function as a

point of materialization of enunciation at the same time as it is this

element that is going to catalyze an existential constellation. It’s

something that isn’t at all extraordinary in the long run since, if you

think about it, in the entire cybernetic economy, there is the

“formalism” function of significations that are articulated in many

signs, but there is also the material function of the sign that

functions like a signal, like a release mechanism (déclencheur),

a material release mechanism with its own energy, with its own

consistency, with threshold phenomena. So I think that it’s entirely

essential to forge a “point-sign” category in which semiotics has an

impact in release effects (effets de déclenchement). There is a

particular moment when a sign passes into act, but its way of passing

into act is something inscribed in machines, in recordings, in releases,

in release mechanisms; I’m working on this subject in an article for

one of Prigogine’s colloquia where I’ll speak, an article on semiotic

energetics. There is a semiotic energetics as well.\33

CS: How could one translate this schema into political terms?

FG: In political terms, one asks: what are the statements, what are the representations of images, of echos, of faces that, at a certain moment, result in this: instead of hearing/understanding (entendre) a discourse, a statement is existentializing, and an effect of subjectivity is crystallized, an effect not only crystallized on the mode of representation, but on the mode of enacting (mise en acte)? All at once, that [effect] begins to exist. That’s when saying is existing; it’s no longer when saying is doing or when saying is making exist. From this results the fact that there’s a particular usage of language since a mode of politics can be completely aberrant from the point of view of meaning, like a ritual usage or religious activity. The whole question is knowing if this usage can be compatible with a perspective of desire, with an aesthetic perspective, or another operation, or if it’s a way to construct an a-subjective subjectivity.

3. _A Thousand Plateaus_: “Becoming-woman”

CS: I’d like to return to one of the areas you touched on earlier, i.e. feminism, in order to consider the term “becoming-woman,” whether this conception still functions, if it was a conception that had an historical specificity at a given moment or if it’s still valid today. It’s a term to which certain feminists react in a very negative way.

FG: In the United States? Because that’s not everywhere, there are some feminists who react to it quite well.

CS: In the United States and in France.

FG: About the “becoming-woman” question? I didn’t know.

CS: Oh yes. One objection is that one finds “becoming-woman”, especially in A Thousand Plateaus, in a kind of progression — becoming-woman, becoming-animal, becoming-child, then becoming-molecular, and finally becoming-imperceptible –, and so the question: why “woman” at the beginning of this progression? Why is there this sort of questioning of femininity? Where is the woman, where is the woman’s body in all that?\34

FG: There is no rigorous dialectic, there is no series of connections like The Phenomenology of Mind.

But simply, the departure from binary power relations, from phallic

relations, is on the side of the “woman” alternative; the promotion of a

new kind of gentleness, a new kind of domestic relationship; the

departure from this, one might say, elementary dimension of power that

the conjugal unit represents, it’s on the side of woman and on the side

of the child such that, in some ways, the promotion of values, of a new

semiotics of the body and sexuality, passes necessarily through the

woman, through “becoming-woman”. And this “becoming-woman” isn’t

reserved to women, this could be a “becoming-homosexual” . . . To

present this simply, brutally: if you want to be a writer, if you want

to have a “becoming-letters”, you are necessarily caught in a

“becoming-woman”. That might be manifested to a great extent through

homosexuality, admitted or not, but this is a departure from a

“grasping,” power’s will to circumscribe that exists in the world of

masculine power values. Let’s say that this is the first sphere of

explosion of phallic power, therefore of binary power, of the

surface-depth power (pouvoir figure-fond) of affirmation.

Obviously, it doesn’t end there, for this “becoming-woman” is

nonetheless to a great extent in a relationship, even indirect, of

dependence vis-?-vis masculine power so that it might rapidly be

reconverted into the form of masculinized power.

There are other becomings that are much more multivocal, that are much

more liberated from this bi-univocity, from these binary relations of

woman-man, yin-yang, etc. So these are the other becomings that you’ve

enumerated that . . . well, it’s obvious that animal-becomings, for

example in Kafka, offer an exploratory spectrum of intensities, of

sensitivities, that is much larger than a simple binary alternative,

that also exists in Kafka, but there are binary machinic alternatives in

his work: think of his magnificent short story, “Blumfeld”, where you

have a little ping-pong ball bouncing like that. So, the

“becoming-woman” has no priority, it’s no more of a matrix than a

“becoming-plant”, than a “becoming-animal”, than a “becoming-abstract”,

than a “becoming-molecular”; it’s a direction. Toward what? Quite

simply, toward another logic, or rather a logic I’ve called “machinic”,

an existential machinic, i.e. no longer a reading of a pure

representation, but a composition of the world, the production of a body

without organs in the sense that the organs there are no longer in a

relationship of surface-depth positionality, do not postulate a totality

itself referenced on other totalities, on other systems of

signification that are, in the end, forms of power. Rather, these are

forms of intensity, forms of existence-position that construct time as