One.

The transcendental is not a condition of possibility. There is no such thing as a condition of something that is merely possible if there are not already actual things that define the immanent relations of the field to begin with. Transcendental re- lations are therefore extrinsic and not intrinsic. Before there are folds distributed according to their degrees of flux in a field, there is no preexisting field to order them. A field without folds or things is just an unordered flow. Conditions of possible motion presuppose an independence or transcendence of the conditions beyond the folds or things that are conditioned. In short, possible conditions are an idealist abstraction.

Two.

The transcendental is not an empirical condition either. The conditions of em- pirical things cannot be other empirical things. If they were, there would be no tran- scendental difference between the conditions and conditioned. Everything would simply be empirical all the way down, without any relations or field of circulation to order them. Logically, moreover, if the conditions for the empirical were also em- pirical, then we would have failed to explain the conditions of the empirical. We would have tautologically presupposed precisely what we set out to explain: the empirical itself.

Three.

The transcendental is not a universal condition. If the transcendental field is kinetic and actual, then it is necessarily historical, and if it is historical, then it cannot be universal, since all of history has not happened yet. The future is yet to come. Moreover, if there have already been transcendental fields in the past, and the present is not among them, then it is possible for new ones to emerge in the future following new fields of the present.

Four.

The transcendental is not an idealist or subjective condition. For Kant there is only one kind of transcendental: consciousness. However, such an anthropocentric proposition fails to explain the historical and material conditions of the emergence of that transcendental structure itself. There was a time, Kant must admit, when there were no humans and thus no transcendental structure, then later on there was. Kant offers no account of the properly historical and material modulation that must have occurred in order to produce the transcendental structure of consciousness. Kant thus falls into an ahistorical and ex nihilo creation myth of the anthropocentric transcendental ego by failing to properly historicize its material and nonhuman emergence. Structuralism and post-structuralism similarly fall into the same trap when they fail to account for the generative material and historical conditions of the production of new transcendental fields.

Five.

The transcendental is a real condition. If there is no ontological division between being in itself and being for itself, then each transcendental is a real slice, dimension, or local region of being itself. Since there are a multiplicity of transcendentals, there can be no single or total transcendental of all the others that could wrap them all up. Transcendentals are not separate or individual structures, nor parts in a whole, but are mutable and entangled dimensions of the same kinetic process of materialization.

Six.

The transcendental is kinetic. As Kant says, a transcendental condition describes the “rules” or ordering relations between empirical things. Relations or order are therefore not things. However, a relation, contra Kant, is not a merely ideal or mental faculty, “the unity of apperception”; relations are strictly kinetic relations because movement is neither ideal nor empirical. It is not a thing; it is the kinetic process by which things themselves are distributed. Thus, the movement of things is immanent to the things themselves but not reducible to them or to our perception of them.

taken from here

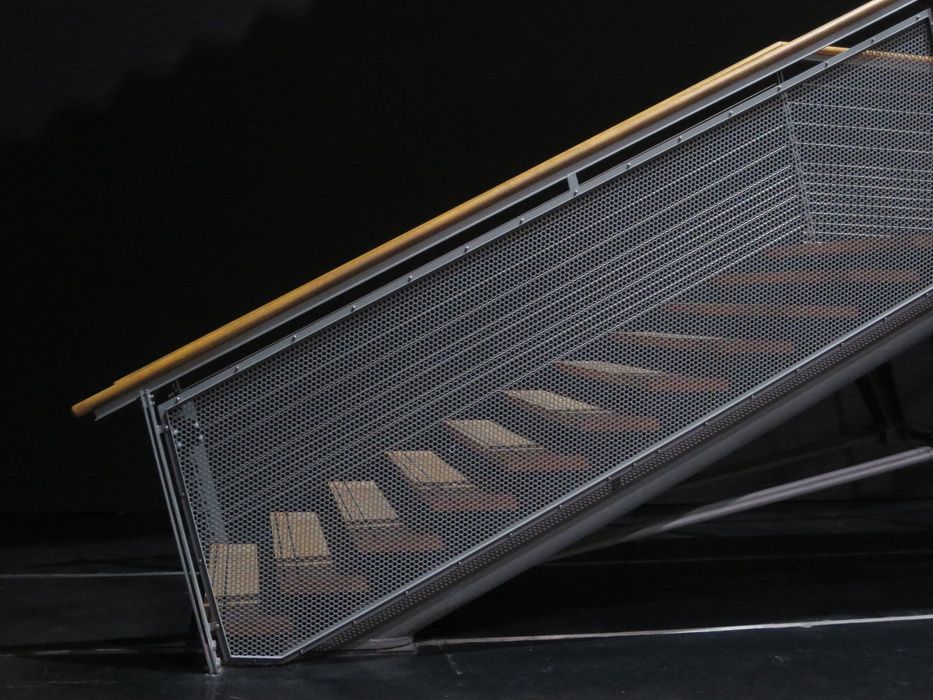

Foto: Bernhard Weber