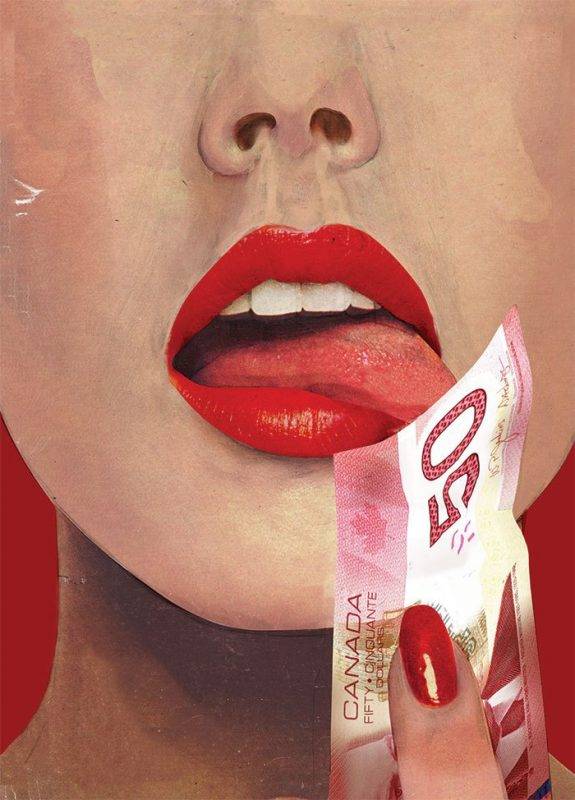

The system is broken. The celebrity is brighter than the sun. Only she can decide when it is day.

There’s a sentiment amongst Swifies that if you wrong Taylor Swift, you will fall. They call it ‘tayvoodoo.’ They say: “tayvoodoo doesn’t work in mysterious ways. it works clearly and bluntly: you’re mean to her, you lose. you’re nice to her, you win. simple.” American football fans booed her, and so their team lost. Kanye West manipulated her, and then his entire public reputation crumbled. Calvin Harris underplayed her songwriting on their song, now he’s irrelevant. Fashioning herself as the moral centre of the universe, she has a map of buried hatchets and is ever-ready to avenge the wronged when she’s “on [her] vigilante shit, again.” Taylor Swift was a girl who felt like a victim – sometimes rightfully so – she has grown into a woman brutally skilled at self-defence, with a solipsistic definition of what that entails. In her quietest moments, she co-opts the worst things people have said about her and turns them into a performance of keening self-awareness. Elsewhere, she spits out her enemies’ unflattering narratives until they glom acidic to the face. This paradox of anti-hero and good girl comes to a head in ‘The Archer,’ when she wonders what to do with herself: “I’ve been the archer / I’ve been the prey.”

Except, with a persona as strategically sanitised as hers, we are led to believe that the only arrows she’s slung are at famous ex-boyfriends or evil producers who started it. Certainly, this is the only archery we will hear about in her music and public statements. Dazzled by her shimmering yet opaque self-presentation, we feel honoured to access her vulnerability in romance and art. As far as the rest of it goes (politics, feminism, economy), we work with what we’re given: private jets bad, bonuses to her tour crew good. Taylor Swift has mastered the binarist form of right/wrong public discourse in the attention economy such that it either points in her favour or is drowned out by opalescent fresh music. Reincarnating herself with a new soundscape and matching outfits once a year or so, Swift has continued rotating like the sun, while we seek warmth under her irrefutable aphorisms and elegaic excavations. Over the past 15 years, her star has continued to grow while other celebrities rail against their dwindling shelf-lives. On “Karma,” Swift herself taunts you to “ask me why so many fade, but I’m still here?” Why indeed? Her fans may call it Tayvoodoo. They say she is the embodied moral compass, the last religion we can believe in, a truism of our cultural times, and the music industry itself. Even if she isn’t perfect, they say, to deny Taylor Swift is like denying gravity – you’ll just end up falling. But let me hazard another approach to this question of everlasting legacy and singular dominance. Let me reconstruct her legal mastery, mythology, and cultural totalitarianism.

Juridification – Taylor Swift, The System?

In an essay called ‘The Twilight of Legality,’ John Gardner theorises the demise of legality in the modern age. He describes the increasing invasion of legislative regulations in every aspect of life – think, the complicated and mistake-prone process of filling out your taxes, requirements to link government IDs to your bank account, or intellectual property rights and their muddy disputes. Gardner sees this barrage of legal paraphernalia as antithetical to democratic justice and freedom. He calls the current state of affairs, in the twilight of legality, “juridification,” and explicates its two axes:

1. The sheer breadth of laws renders ‘the law’ in its entirety, unknowable.

2. This vastness means that the law cannot be enforced evenly.

Selective judicial enforcement operates with biases, fears, and vested interests. Powerful groups can exploit the vastness of law to further their particular ends, while marginalised groups are disproportionately vulnerable to eccentric enforcement. In a juridified climate, citizens are turned into large moving targets acting within the omnipotent framework of ever-burgeoning laws. So, the law has become an unwieldy tool of the ruling class. Perhaps it has always been this way, but well, size matters – and in the case of the law, the bigger it gets, the less fair it becomes.

In Taylor Swift’s 72 Questions with Vogue, back in 2014, when asked “What advice would you give to anyone who wants to become a singer?” she replies, “um, get a good lawyer.” In what follows, I show that juridification is a weapon in Taylor Swift’s arsenal. And metaphorically speaking, juridification has done to legality what Taylor Swift has done to culture.

I must first clarify some points before we may talk of ‘singularity’ and ‘scale.’ It is difficult to, either quantitatively (through sales, net worth, or awards) or qualitatively (through an objective hierarchisation of cultural products) provide an indisputable metric for ‘fame.’ First, there are contextually contingent variables like streaming or internet relevance preventing me from drawing transhistorical comparisons with say, The Beatles or Michael Jackson. And then there is the reality that in our postmodern, globalised world, culture has expanded, mutated, and infected our lives without needing a specific mediatic vector to transmit itself. Living in the age of so-called ‘democratised’ content, we consume so much, and so frequently, that culture eludes concretisation; quite like the law in a juridified system, it pervades the everyday. There are indeed other megastars with tremendous influence and institutional legitimacy – say, Beyoncé, Drake, and Bad Bunny. When everyone is a consumer with at least some level of agency in choosing what they will listen to from millions of options, a ‘monoculture’ can hardly exist. This is why it is no use arguing over linear claims (‘Taylor Swift is the most famous person to ever exist’). These lead to the sorts of fights best reserved for Twitter replies. Instead, by creating a framework for Swiftian criticism, we can get to the bottom of an indisputably mammoth phenomenon, and then interrogate other celebrities whose modalities may hinge on different levers. Thus, our focus is on a periodising analysis of what a dominant cultural presence looks like, and its ideological consequences (‘Taylor Swift is prolific and neoliberal presence has led to cultural totalitarianism’). By thinking through a conscious silo, we can plumb at these big ideas of ‘cultural dominance.’

The Polyester Podcast references a tweet qualifying Taylor Swift’s fame: “how many times a day do you think about taylor swift against your will.” Needless to say, I trust that you have seen the headlines and leotards; you’ve heard the rabid crowds and resplendent hits. Here is some personal context (as to why we can proceed on a first-name basis). I was introduced to Taylor at age 9 or 10 by a friend while we played basketball. I was wearing knee-length checked shorts and some football jersey or other. My friend said I had to listen to this song she heard on the radio – it was about a girl who wears T-shirts, not short skirts! Say less! A few years later, ‘RED’ became the first album I successfully ‘Torrented’ on the family computer. ‘1989’ brought me my first artist merch. I’ve had, at some point, swiftie accounts on Instagram, Tumblr, and Twitter. I can do the ‘name the Taylor Swift song in 1-second challenge.’ Easily. I’ve been in the top 0.001% of her Spotify listeners (in a particularly emotionally unstable year for me, but nonetheless). A few months ago, I spent an amount of money I choose not to disclose on Era’s tour tickets, for which I flew to Singapore. When I begrudgingly told people how much I spent on tickets, they said, ‘that’s insane, but it makes sense for you.’ I hope these credentials suffice. Let us move on then to the accusations.

Since the Grammys, there’s been a shift in the cultural temperature on Taylor. In part, this is but a standard inflexion of the cyclical relationship of love and hate the public has with Taylor. Yet, this time, the problem is not ex-boyfriends or leaked phone calls, it is more insidious. We learnt that she had an exclusivity deal with the Singaporean government, receiving millions of dollars in subsidies for playing nowhere else in South Asia – forcing fans with means to fly, and fans with none to suck it up. We also learnt that Taylor threatened to sue a 21- year-old college student who was publishing information about her private jet’s movements. How could sharing already-public information constitute the endangerment of life? It gets worse: Elon Musk kicked the student off Twitter last year for the same reason.

Evidently, these billionaires are being litigious as a form of censorship. Legal action was the chosen course only once there was scrutiny and backlash. When Taylor wasn’t losing favour because of the data, apparently the student’s actions were not illegal. Suddenly, after trends and takedowns for her 13-minute flights, they maybe could be. So what if an addendum to a legal text from somewhere or the other could construe these social media posts as the endangerment of life if she were to sue? Nothing about this is fair. It’s a symptom of a society in the grips of juridification.

The familiar argument goes: criticize systems, not individuals. But can we read Taylor Swift as a system unto herself? On the front of her carbon footprint, despite her being the highest polluting celebrity, she is still far from most corporations in the top 100 polluters. Yet, what makes her footprint newsworthy is that she threatened legal action – against not even a whistleblower – just a student with an Instagram account. She would never have had to sue, the threat was enough of a deterrent. It’s easy to point out why this is disconcerting – power asymmetry, environmental irresponsibility, and institutionalised censorship. Taylor weaponized the law to control the narrative, in a thoroughly undemocratic, unequal machination. But the problem is bigger. It doesn’t matter that this time she used her magic powers of institutional intimidation for wrong. The problem is that she – as an individual – has the capacity to do institutional intimidation at all.

Only to a largesse like Taylor Swift would the juridified legal system be a tool and not a tyranny. This is a cold, winking, ‘bury them in paperwork.’ The average person cannot dream of seeking remedy through the behemoth of law because the cost of entry exceeds their capital. Meanwhile, Taylor has threatened to sue (deep breath): her ex-guitar teacher for buying the domain “itaughttaylorswift.com,” fans on Etsy for selling merchandise bearing her name, an Australian graffiti artist who made an objectively horrific mural, two podcasters, 24 unidentified trademark violators, Microsoft, and Kimye. And, all this research is from 2017, the last time tabloids hated her enough to find this out. Other artists have threatened to sue merchandisers for using their name – like Drake – but they have largely threatened major retailers like Macy’s and Walgreens, not fans barely turning a profit on a website. By 2015, Taylor had applied for 121 trademarks (almost 10 years ago). Yes, other major artists have caught wind of these practices and many have, literally, followed suit. But none with the frequency and fluency of Swift.

A few months ago, disgusting, unconscionable, and sexually violent AI-generated photos of Taylor went viral. The promptest response came from the fans, who scraped the images off the internet to protect their star. They mobilised with their usual cultish deft and large-nation-sized population. Next, the general public reacted in outrage, and finally, in response to the outrage, lawmakers began reviewing the scope for legislation to prevent such tragedies.

This is an objectively worthy outcome of a twisted situation. But it does matter that this is what it took. A Guardian article notes that there are upwards of 9,500 sites dedicated to nonconsensual deepfake porn, and that this technology has exploited child sex abuse. Yet, the title of the article documenting historical terrors is: “If anyone can get the US government to take deepfake porn seriously, it’s Swifties.” The author sees the mobilization of fans as a “silver lining.” Indeed, we are transacting in an attention economy, and pressure is always needed to realise any large-scale legislative change. However, when activists have been fighting for years to make better laws for women’s protection, and girls have died by suicide over deepfake porn – it is bewildering that this is what it took. The system is broken. The celebrity is brighter than the sun. Only she can decide when it is day.

Under the regime of juridification, the notion of injustice has been concentrated onto individual right/wrong, and modified to accommodate said individual’s social and economic capital. This is both a cause and result of the realism with which we encounter broader systems of power. The superstructures of today’s world – capitalism, neo-imperialism, patriarchy – are interwoven into a bureaucratic and ideological hydra whose heads can never be cut off. Power is no longer wielded by a single sovereign against their subjects. Instead, it is diffused and upheld by a host of interacting identities and ideologies. In the brisk air of the internet, through the hot spillages of media, our compasses for morality must cast their gaze everywhere and nowhere, for that is where power thrives. We are beholden to the vagaries of algorithmic ritournelles and post-truth chatter because these are our sources of ideology, morality, and consumption.

When a singular force such as Taylor Swift rises and grows tall, tall enough to touch the superstructural sky, it is not enough for us to applaud when she forces change in the music industry’s worst habits. These, and most of her moral-legal triumphs, guarantee the victor monetary spoils. Her ‘activism’ is consumer activism – starting and ending with protecting the dominant ideology’s faith in private property, commodified art, and individual ascendency. Her ecosystem sees private ownership as a virtue and critical rhetoric as unlawful. Yes, wrong is wrong. It is disheartening that in our lurid world of so much negative media coverage and so little attention, not all wrongs were created equal.

Taylor Swift has said nothing on Palestine. (I will not count attending a comedy show with proceeds donated to relief efforts and then saying nothing more on the matter as ‘registering dissent’). The actual colonial state of Israel tweeted: “we promise that we’ll never find another like you,” tagging her. Another person tweeted: “i genuinely think taylor swift could change the trajectory of world politics by tweeting free palestine.” When her undying star has the proven power to shape public opinion on morality (no one in the general public seriously considered it unjust to not own your masters before her), then we have entered a brittle new world. One where Presidents beg Taylor to tour in their silly little nations, historical monuments are renamed to pay her respect, and a single Instagram story from her can increase voter turnout so drastically that it influences the outcome of an election. She’s a recession-proof price-inelastic commodity; she is the hopeful democratic party’s silver bullet. In her Time Magazine interview for being the Person of the Year in 2023, the journalist characterizes Taylor’s deserving of this award primarily on grounds of scale: “To discuss her movements felt like discussing politics or the weather—a language spoken so widely it needed no context. She became the main character of the world.” Well, if we grant her all this power, we must crucify her for its misuse.

At the recent Super Bowl, while Rafah, a declared safe area for Palestinians was bombed, everybody was watching Taylor and her boyfriend. In order to be a functionary of ruling class hegemony, Taylor Swift does not need to be a liberal psy-op, as suggested by the erudite folks of the right wing. (The right-wing is correct to point out that ‘the system’ is working in a manner of unfreedom. Unfortunately, they get cause and consequence so wrong you cannot take them seriously). She simply needs to continue existing as an acquiescent friend to the neoliberal system. Her fans defend: she isn’t asking for the camera to be pointed at her! But her brand has gestated and come to life by dint of photographs, blurred lines of personal and public, and transfixing eyes – all of them – on her. She provides partially differentiated products (albums, outfits, easter eggs, boyfriends) that, under the guise of ‘apoliticality,’ enable the continued injustices of the status quo. Her existence on this scale is sanctified and sanctioned by the superstructures of our times. If we live in a juridified system, she has made it her armour. If we live in an attention economy, she has monopolised the market. If we live in the culture industry, she is simultaneously its shiniest product, and deftest producer.

Taylor Swift – The Culture Industry

In The Dialectic of Enlightenment, Adorno and Horkheimer theorise our engagement with media as the “culture industry.” The term describes the state of culture wherein freedom is lost both creatively and politically, because alienated people uncritically consume artefacts that reproduce dominant ideologies. The mode of production in the culture industry is that of the Enlightenment – rationality. All must be measured for target groups, scraped clean of the offensive, and rolled out with the inflexible rhythm of an assembly line. This rationality becomes a totalitarian cultural force, by subsuming all artistic endeavours, compelling them to be organized and driven by the market’s principles of efficiency. In mandating such precision and vacuity, totalitarianism sustains a society that is “alienated from itself.”

In a lovely podcast about the Culture Industry, the hosts bring up Beethoven, Radiohead, and Taylor Swift as countermodels to the culture industry. They claim that each of these megastars successfully liberated themselves from the requirements set forth by the dominant artistic-economic production machines of their times. Beethoven refused to live with a patron, choosing instead to build relationships with more experimental supporters of his art. This retained his ingenuity and craft. Radiohead, tired of the creative limitations and steep prices wrought by a record label, released their album ‘In Rainbows’ for free, letting fans pay as much or as little as they’d like to hear it. In this way, both were able to supersede the culture industry’s restrictions of economic efficiency and creating a product bound by the market’s logic. They could then create with disregard for selling as much as possible, having already secured a loyal coalition that guaranteed their existence. This led to freedom to create outside the culture industry, untainted by appeasement tactics and performance metrics.

The hosts then extend their argument to Taylor Swift, suggesting that because of her scale, it is likely that she, too, can escape the machinery of the culture industry. I agree that her scale has allowed her to become an autonomous market with its own coalition, but do not believe this has been through rejecting the totalitarian rationality of the culture industry. Where Radiohead formed autonomous platforms to increase the availability of their music to fans, and Beethoven’s patrons granted him greater scope for countercultural composition, Swift’s autonomous economy bows down to neoliberal capitalism, delusions of Americana, and plain avarice. These principles have been Taylor’s buttresses, scaffolding her very own hypercapitalist culture industry.

Taylor has made herself an essential truth of society, naturalizing herself through familiar ideological games. She has entreated each reigning system of power to swear fealty to her, because she has sworn fealty to them. She will protect their values and principles with all her heart (and lawyers and billions) as long as they give her the same privilege.

Taylor says, often, that she has had to stand up to systems that slut-shamed her for having too many boyfriends and being too surprised. In the Time Magazine article, Taylor calls ‘reputation’ – an album mostly full of love songs, “a goth-punk moment of female rage at being gaslit by an entire social structure.” She is so severed as an entity from the structures of oppression that public disapproval – while mean and misogynistic – has been turned into disenfranchisement. Neoliberal ideology demands this kind of posturing, which empties out and co-opts the vernacular of genuine resistance. Far from being some kind of contrarian catharsis, ‘repuation’ proved, as a VICE article notes, that “Taylor Swift is Too Big to Fail.”While critics largely panned the record, and ‘haters’ slithered in her comments section, it became the best-selling album of the year, selling more than double of the next albums on the list. It did not matter that the ‘mainstream’ market rejected her. She is a mainstream unto herself. But had she done some shady things to get there? In the VICE article, the author talks about how, in the run-up to album release, Taylor threatened to sue several publications, so many, in fact, that another article asked: “Has Taylor Swift’s Lawyer Threatened to Sue You? Let Us Know!”

After years of silence on America’s two parties, she claims that when she realised she ‘had to say something,’ she came out as Democrat. I don’t buy that. I believe her calculus shifted: it was becoming costlier to not disclose her politics, than to say she was a democrat. (Many publications, that she threatened to sue for libel had started to call her a Nazi). I don’t suggest she is secretly a Republican, rather that she is a chameleonic nothing, computing politics through an assessment of the zeitgeist’s mathematics. This is why she can be criticised for being too right wing, too left wing, and too centrist all at once.

When neoliberalism deems a concept ‘normalised,’ it has appropriated that movement into the rational moral consciousness. Hence, the marginal cost of making a song called ‘You Need to Calm Down,’ telling homophobes – in the vein of all great activism – to chill out, is far outweighed by the benefits of appeasing a moment’s norm. When it was the normal position to adopt, Taylor mobilized her army and did genuinely impactful things (donations, petitions, etc). The needle for morality had already been shifted through the hard work of activism, she coasted in once all the discomfort around queer rights had passed. Her glistening image is deliberately placed in the marketplace of media as an anodyne, unsexy, formless protean. It would be foolish to expect her to soil her best dress with radical empathy.

The culture industry requires that its products embody this tepid, mass-apeal-based moral rationality. It can never say, speak on Palestine or Indian farmer protests, but it could, reasonably, peddle an LGBTQ+ flag and talk Biden. It is the cowardly white liberal feminism that revels in its fetishisation of individual agency and ‘choice.’ Accordingly, Taylor has turned the personal pronoun, ‘I’ into the sharpest, most well-organised institution seen in modern culture. Even in the age of stan Twitter and internet insanity, she has the most rabid of the bunch, who have scared music critics by doxxing unflattering reviewers to protect her ‘I.’

In return, Taylor uses this large fanbase as a cash cow that will purchase 4 Vinyl records of the same album only because when you arrange them, they form a clock through their cover art. (Seriously.) Her fans stream remix after remix to climb the charts, and have moralised her re-recordings so well that purchasing a Taylor’s Version is recast as a display of love and loyalty and feminist consumption. (On stan twitter, the older versions are called “unethical versions.”) And all the while we are to believe that her predatory and rapacious marketing efforts, her (in my opinion) ugly, overpriced merchandise, and her single-minded gamification of streaming metrics, are supposedly irrelevant to her musical genius.

In that same Time Magazine interview, she explains Girlboss feminism 101 as if she invented it (is Sheryl Sandberg a joke to you?): “feminine ideas becoming lucrative means that more female art will get made. It’s extremely heartening.” Taylor has turned the logic of production and its efficiency into a virtue, proof of talent, feminism, and a mandate for a legacy. This is the work of ideology. It manipulates its subjects from realising superstructural oppression. It brazenly invokes identity politics. It piggybacks off of movements with teeth and blunts them into blubbering, white individualism.

Taylor recognises that the culture industry was responsible for making artists play the capitalist game of profit-maximisation: this is why she fought Apple Music and Spotify for better compensation. In an interview with the Rolling Stones speaking against streaming, she said: “And I just don’t agree with perpetuating the perception that music has no value and should be free.” Her problem with these platforms was not the commodification of art itself, but that she was not profiting enough from this commodification. She was able to hold them hostage because the platforms needed her more than she needed them, and this is what it means to rule one’s own culture industry. Her output is – after all – songs she wrote about herself, by herself. In our late capitalist context, when economic avarice has been naturalised into ‘business savvy,’ we forget that consumption is a political act. Marketing and releasing partially products for the sole reason of more profit is a hostile, exploitative, totalitarian act.

Taylor Swift – The Myth

We must now get to the music itself, so allow me to borrow from Barthes’ description of Myth to make the following claims:

1. Taylor Swift is a storyteller.

Across Taylor’s discography, form and style are both only window dressing for the storytelling impulse. It’s all about angle. She’s said it herself– it doesn’t matter if it’s the icy synths on ‘1989,’ or fiddle twangs on her debut record, the heart of her work remains the same: images and actions weave themselves into conceits that are as repetitive in their structure as they are compelling in their world-building. She has never sold us sex, with its risks of post-nut clarity and inevitable somatic changes. She chose, instead, things that stay with us forever – we remember crushes through her titles, choose date spots through her hooks, and explain heartbreak by her bridges. Her folklore is water, seeping into every structure of feeling, buoyed eternally by its narrative arcs that are always about things. For most people’s romantic lives, you could reasonably say – hey! There’s a Taylor Swift song about that!

2. Her music is a Myth: Unlike polysemic art, which abounds in all directions and invites the reader to participate in meaning-making, this all refers back to its own mythology – that of Taylor Swift.

In semiotics, linguists break down the process of signification: there is a complete sign which is made up of signifiers – the vehicles of representations chosen by a cultural system (like saying ‘cat’ to describe a cat)- and the signified, which is the thing itself (that animal with some milk and meows). Barthes explains myths as a second-order language system, wherein what was once a sign (concept of cat + image of cat) becomes just a signifier (for spinster, or bad luck, or cute, depending on the myth).

My claim is that Taylor’s music makes itself a second-level signifier for her own Myth. She makes the act of listening to her music an act of trying to get to the bottom of the first-level of signification, in order to plumb at the second-level of signification, which is her Mythology.

Swift’s music presents a series of signs for emotions – love, heartbreak, and joy – woven into linear arcs. However, these arcs do not leave much room for the emotions themselves to explode beyond the narrative structure she has erected with hook-machines and chord-cement. Barthes tells us that the triumph of Myth is its ability to never reject things or mottle them. Instead, “its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification.” In other words, her reams on the rituals of relationships perform a purifying function, clarifying the messiness of emotions through the imposition of a language system whose framework is order, logic, and realism.

These narrative arcs, furthermore, are replete with meaning that can be uncovered and further purified through a cipher-style listening process. Unlike more interpretatively complex singer-songwriters, (say, Björk, or Fiona Apple) her lyricism, while powerful as a series of fatally-precise adjectives and remembrances, form a lexicon for emotions that creates distance from the emotion itself. Her songs are more interested in spinning a story around an emotion, than the emotion and its catharsis. In other words, they all tie back to story, to self, to myth.

3. The more time you spend with both Taylor the woman, and Taylor Swift’s fandom, the closer you get to Myth.

One of Taylor’s greatest songs, ‘Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve,’ is a deep cut off ‘Midnights’ that documents a debilitating relationship with an older man. Her grief is naked and gutting, with lyrics like, “give me back my girlhood, it was mine first,” and “I miss who I used to be/ the tomb won’t close,” and “I regret you all the time.” Her voice – as always – is clear as a missile, inflecting at the proper moments and crooning at each loss, making sure you understand how each word felt in the story of the song. When the song was released, me and many other dedicated Swifties said the words our coven demands us to drop at least once an album cycle: this song was written specifically for me, about my life.

This is the brilliance of Myth: “it comes and seeks me out…as a confidence and a complicity… I feel this [song] has just been created on the spot, for me, like a magical object springing up in my present life without any trace of the history which has caused it.” There is much discourse around how, because Taylor’s vocal range is limited, her songs are easier for the average person to sing. It’s not about hitting the high notes, it’s about achieving the emotional intonation as prescribed. That’s what delivers the fulfilment of enjoying a Taylor Swift song. To properly appreciate the song, you have to listen to the lyrics and sing the story. You have to find the protagonist sympathetic or antagonistic as prescribed by her Myth. If you are faint of heart and a lover of stories, you cannot help but invest in the first-person character she embodies, and you cannot help but construct yourself in the first-person character she entreats you to learn-by-heart. That’s how you begin to speak the metalanguage of her Myth.

Taylor’s prolific musical exegeses have created not a discography, but a Myth. This is what makes her fans feel as though they are speaking a secret language, and living in a world of interiority where it is only them, their secret sessions, their reserve of references, and their own red-lipped Rosetta Stone. This is not polysemic literary interpretation, because there is a right answer as to what refers to what, which you can understand if you sink deep enough into her mythology.

Cultural production under late capitalism is characterized by its intertextuality: nothing is unique, everything is a referent of something else that has come before it; all is bastardised kitsch and layered with quotations, simulacra, and symbols of other cultural artefacts. What makes Swift feel like she means more is that from the singularity of her vision and her magnificent power to produce prolifically, all ties back to her own Myth. She does not have to debase herself with external borrowings and imagery; she has no reference point but herself. Roland Barthes describes: “Myth…establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves.”

I, seasoned Swiftie, recognise not only the songwriting easter eggs within ‘Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve,’ but also that it is the 19th track on an album she released at age 32 – obviously, this is a metacomment on 32-year-old John Mayer dating 19 year-old Taylor Swift. Duh. The web never ends, there are no limits to her omnivorous mastication of language, her oeuvre is an exercise in scarfing down images and symbols and regurgitating them as her own Myth. Lest we forget, she also has juridification: In an insane, must-read essay ‘Taylor Swift Does Not Exist,’ Sam Kriss offers a screenshot of a diary of notes made while following the ‘1989’ tour, shortly after Taylor copyrighted ‘this sick beat,’ ‘nice to meet you, where you been,’ and ‘party like it’s 1989.’ They are the scribbles of a madperson, but they are right: “she is attempting to PRIVATISE ALL HUMAN LANGUAGE” in order to “make it so it’s IMPOSSIBLE TO SPEAK WITHOUT ONLY SPEAKING OF TAYLOR SWIFT.”

By offering so many stories across so many genres, as Horkheimer and Adorno write, “[s]omething is provided for everyone so that no one can escape.” Her ocean of cultural output flows with the pull of language-learning. The more you listen, the more you connect, the more you understand the Myth of Taylor Swift. You can remember the necklace from the paparazzi photo and use it to decode an epithet in a hit. You can watch her music video a million times and find a new album title. It is not ‘high art’ that has multiple possibilities. It is the deadening out of artistic possibility, being so invested in an individual’s myth and truth. This is why Taylor Swift stands out: by gamifying her cultural output, she has added another layer of engagement with it that is ostensibly ‘depth’ of interpretation. The pleasure delays its own gratification for a second, invites a semi-automatic form of engagement, and eventually reveals itself as metalanguage. Determined not to give up the appearance of intellect while in fact eroding its cultural roots, we flitter through loose, laden, Swiftian songs and accomplish “not only…a depravation of culture, but inevitably…an intellectualization of amusement.”

Because of this participative element of stanning Swift, new music is encountered with a kind of high: to recognise a variation or adaptation of an older album, ex-boyfriend, or album-drop tactic, a user is validated as part of the in-group, well-versed in the mimetic ontology of the group. Each new cultural output from her (song, outfit, outing, boyfriend) is satisfying irrespective of the quality of the creation, since the fear of missing out on a cultural moment is so stark, the threat of irrelevancy so debilitating, and hence, as Adorno and Horkheimer write, “enjoyment is giving way to being there and being in the know, connoisseurship by enhanced prestige.” Then, any additional differentiation made by the creation is championed as innovation, despite these differentiations’ subscription to the same format and ideological scope of the Taylor Swift Universe. It’s Marvel, with some SAT vocabulary and an enthralling bridge thrown in there. Dialectic again, “the machine is rotating on the spot.”

This ritualistic engagement with music as a form of amusement is particularly rewarding under late capitalism, when our leisure time – thought to be a place of freedom – has turned into anything but. Under late capitalism, the time we do not spend working is time we must spend preparing to get back to it the following morning, and it is time we cannot spend critically questioning this fact. Of course, not all Swifties are 9-5ers breaking their backs over labour, but the sociological shift in our leisure necessarily affects every consumer of the culture industry, for we cannot help but think in the grooves of work. When Taylor offers us a treasure map and a legend, the faculties for work which ideology has been training us to take up since birth leap back at us as pleasure. This offers the appearance of singularity in our pop culture landscape which has been socialised into an alienating world, where we do not ‘engage’ with culture, we consume it as entertainment. By and large, culture is entertainment, and everything else is pretentious. Our leisure time is spent re-watching old shows, scrolling until our fingers ossify, and adaptations of adaptations are all that’s left on the air. Most of what we consume in our postmodern world is both boring and pleasurable, demanding little effort and content with the slopes of the familiar inundations of media. Thus, Taylor speciously demands more of us, the brains we’ve wired to work, and we oblige, glazed over and content.

These conditions have a degrading effect on culture at large; there is no choice but to amuse and puzzle, and thus, what was supposed to be the great democratisation of content has actually been a juridification of culture. There is too much of it, it serves to reproduce the ideologies of the status quo and its hegemony, and the more of it there is, the less meaningful our engagement with it gets. Art is degraded into schlock that serves to unify the masses through output that by design must never question the systems structuring life under late capitalism. The culture industry facilitates the collective numbing of our weirdest, most dangerous, and revolutionary impulses, by feeding us a never-ending supply of base entertainment. It reduces art to the distractions of fun, and with our diseased alienation, “fun is a medicinal bath which the entertainment industry never ceases to prescribe.”

Taylor Swift, My Close Personal Friend

The word ‘parasociality’ gets thrown around a lot. The New Yorker podcast covering Taylor’s potential creation of a monoculture discusses her Mona-Lisa-esque ability to create intimacy with her legions of fans through a “hey guys” linguistic effect. She walks onto the stage and offers a simple introduction – “hey guys, my name is Taylor” – and hundreds of thousands of people almost faint. We know your name, Taylor. So much of our imaginative and sentimental universe has been handed to us by your songs. These rich histories, where your mind turned lives of a generation into folklore, are unshakeable, and visceral. We cannot deny your role our emotional histories, for to do so, would be like denying gravity: we would end up losing a part of the world that kept us grounded. But there is a point beyond which we must all grow out of our lowest impulses, and I’m afraid, you are this cultural moment’s. There is no doubt that you will continue to be the light of the pop firmament, glowing in adoration and impossible increases in fame. Nobody can take anything from you now. It is time we take stock of what you have taken from us, instead. It we document your systemic transformation into an uncontrollable machine, running riot beyond our formulas for success, quite like the free market. It is time we take stock of your role in replicating the worst parts of feminism, neoliberalism, and shallow cultural output in our degraded climate of consumption. There is a danger to your blinding star. For years, you made it impossible to look clearly at all that you are, and all that you have done. Happy in our heart-shaped sunglasses, humming along to our gospel, we were believers. Now, it is time to step into the daylight, and let you go.