[Note on the translators introduction: Crucial for our understanding of the particular fusion of political activity with knowledge production that comes out of Precarias a la Deriva is their novel use of the Situationist derive. As they note in ‘First Stutterings of Precarias a la Deriva,’ “In our particular version, we opt to exchange the arbitrary wandering of the flaneur…for a situated drift which would move through the daily spaces of each one of us, while maintaining the tactics multisensorial and open character. Thus the drift is converted into a moving interview, crossed through by the collective perception of the environment” (34). One could even say that more than a mere modification of situationist methodology, Precarias a la Deriva’s methodology of the ‘moving interview’ combines the dérive (and its attention to the ways in which the reproduction of urban existence liberates or constrains the precarity that conditions the reproductive labour (unwaged, emotional, affective, sex, and care work), and particularly women’s labour) with the form of the ‘Worker’s Inquiry’ – the latter published by Marx in 1880 and was an attempt at gathering responses to 101 questions from workers themselves with the aim of achieving an exact and precise knowledge of what contributes to or detracts from working class struggle.]

- Sex, care, and attention are not pre-existent object, but rather historically determined social stratifications of affect, traditionally assigned to women.

Precarias a la Deriva begin their argument for a ‘very careful strike’ by understanding that the current form taken by unwaged reproductive labour (sex, care, attention) is the outcome of a long historical sequence. And the common element that binds contemporary unwaged labour to previous instances is the reproduction of patriarchal gender norms; these norms that split subjectivity thereby forcing upon it the choice between the good mother or the bad whore:

“The history of sex and care as strata is ancient. Almost from the beginning of Christianity, both were associated with a bipolar female model, which located on one (positive) side the Virgin Mary, virtuous woman, mother of god, and on the other, (negative) side Eve, the great sinner of the Apocalypse, the transgressor, the whore” (34).

Thus, if reproductive labour is a historical formation and not a natural given, then its chief accomplishment is what Precarias rightly call the ‘stratification of affect’ – the process of rendering certain modes of being (sex, care, attention) as attributes of some bodies (women) and not others (men). And following from the Christianity of the Medieval period we see the reappearance of this stratification of affect, but now in the period of the Enlightenment. The specific process of stratification of the Enlightenment period, however, would become something unlike that of the Middle Ages and would erect legal sanctions in place of religious doctrine in order to modify and reproduce these old divisions between the woman of virtue and the woman of vice and further distinguish one’s womanly virtue (loving-mother, loyal housewife, single-virgin) from her vicious double (transgressor-whore). And it is due to this substitution of secular right for religious judgment, says Precarias, that we can find in places such as the US, Great Britain, and Australia, the creation of laws aimed at regulating the exchange of sexual services for money, ‘which in many areas…included the regulation of the exchange of sexual services for money. It was in this manner that prostitution appeared in the way we know it today, that is to say, as a specialized occupation or profession within the division of labour of patriarchal capitalism, and how it was restricted to determine spaces and subjects (ceasing to be an occasional resource for working and peasant women)” (35). Moreover, and regarding our present moment, it is this historical formation of those strata of affect (sex-care-attention) that have entered ‘into perfect symbiosis with the bourgeois nuclear family that capitalism converted into the dominant reproductive ideal’ (35).

- Our journeys across the city…have led us to abandon the modes of enunciation that speak of each of these functions as separate and to think…from the point of view of a communicative continuum sex-attention-care.

Given the historical stratification of these affects it is not hard to see why, for Precarias, they belong to one and the same continuum, to the same historically formative process (and all the better to emphasize “the elements of continuity that exist under the stratification…in concrete and everyday practices”). However, Precarias also give another justification for their understanding of these stratified-gendered affects: their ‘journeys across the city’ and placing their ‘precaritized everyday lives’ under close examination. And what is discovered is that it not solely the work of history that certain affects have become seemingly natural attributes of particular subjects. In addition, what is discovered is the increasing complexity by which this historical stratification is carried out. Hence, “a continuum because…the traditional fixed positions of women (and of genders in general) are becoming more mobile, and at the same time new positions are created. The whore is no longer just and only a whore…the sainted mother is no longer such a saint nor only a mother.” For Precarias a la Deriva, the stratifications of affect proper to the present cannot and should not be understood in light of its previous iterations (i.e. via mere substitution as in the Enlightenments replacement of theological doctrine with secular law). Today, the stratified (re)production and (re)alignment of social functions such as sex, care, and attention can only be understood on the basis of their increasing ‘mobility’ or ‘diversification.’ But what is exactly mobile and diverse about the contemporary gender division of labour? The present stratification of affect is

- diverse due to the increasing variants of the classical ‘sexual contract.’ This ranges from traditional matrimony and sex-work (prostitution) to the renting out of women as surrogate mothers, to the well known phenomena of spouses for hire (‘mail order brides’). And with this transformation in the sexual contract (i.e. the social relations that regulate sex, sexuality, and reproduction) follows a transformation of the model of the Fordist nuclear family (‘and the proliferation of other modality of unity…monoparental or plurinuclear homes, transnational families, groups constituted by non-blood bonds…’).

[and]

- mobile insofar as what once was accomplished in the home is now outstripped and accomplished by the market (“many of the tasks that were previously conducted in the home now are resolved in the market”) – e.g. fast food/ready meals, which accomplish a mother’s daily task of meal preparations, or middle-, upper-middle class, and wealthy (white) women (residing in the global north) are relieved of their duties of childcare by hiring women from the global south to carry out what once were her traditional roles of caring- and domestic-labour, and so on.

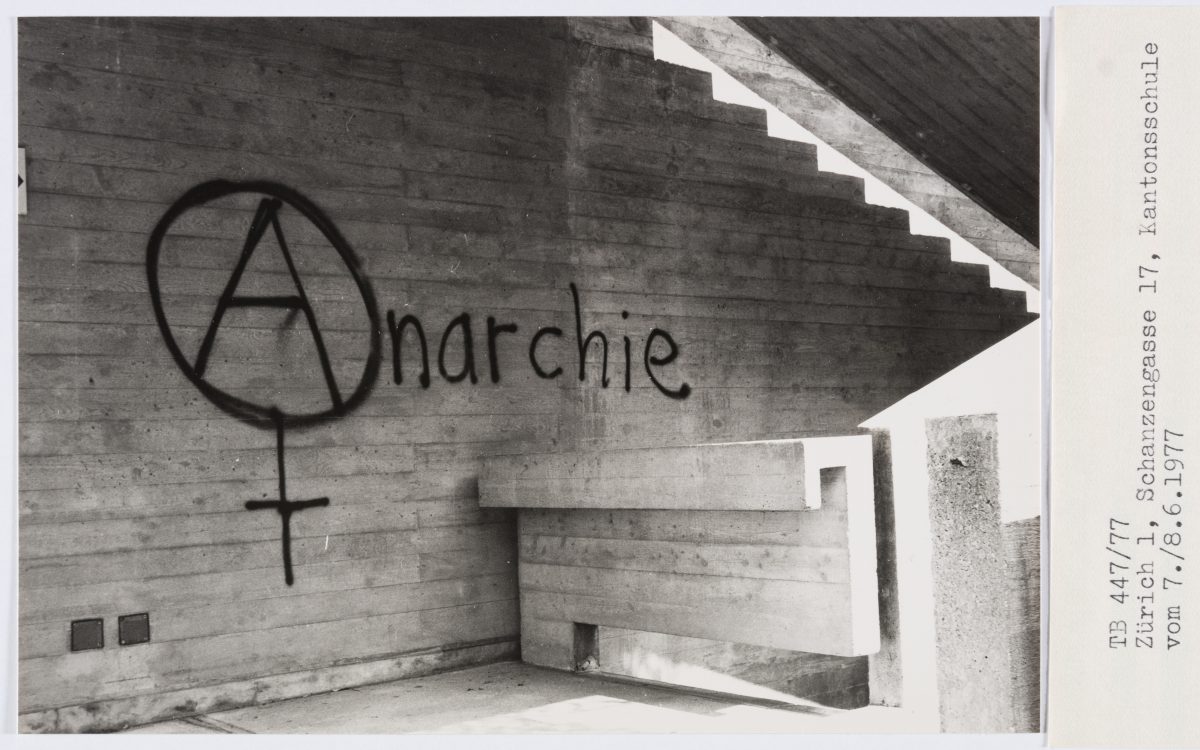

In the end, Precarias are right to emphasize the novelty of this novel stratification-(re)articulation of the gender division of labour, since this stratification is a process whose outcome is the condemnation of more and more individuals to live under conditions of an ever deepening uncertainty. And just as the increased variations of the sexual contract corresponds to a crisis of the traditional nuclear family, so too does the ‘externalization of the home’ correspond to, what Precarias call, ‘a crisis of care’ – and a crisis that begins with the decline of the Welfare State. So, along with the ‘crises’ (or transformations) in the forms of familial and domestic labour, there exists a corresponding transformation in the very ‘physiognomy’ of precarious labour and realizes itself the now common phenomena of one’s “lack of time, resources, recognition, and desire for taking charge of nonremunerated care.”Moreover, says Precarias, these crises – of the family, domestic labour, and of lack – are circumscribed by a fourth and final problem: “In last place, we have urban question: the crisis (and destruction) of worker neighborhood and their strong sense of community has given place to a process of privatization of public spaces.”

- Care, with its ecological logic, opposes the security logic reigning in the precaritized world

Now, just as this socio-economic stratification of the sex-care-attention continuum as ‘capitalist axiomatic’ (i.e.all degrees of difference along the continuum are convertible into value) the contemporary norm of governance on the part of nation-States is that of a ‘macropolitics of security,’ which realizes itself in the ‘micropolitics of fear.’ For Precarias, it is in light of the logics of security and fear that govern everyday life that precarity finds its other meaning:

In this context of uncertainty…precarity is not only a characteristic of the poorest workers. Today we can speak of a precarization of existence in order to refer to a tendency that traverses all of society…Precarity functions as a blackmail, because we are susceptible to losing our jobs tomorrow even though we have indefinite contracts, because hiring, mortgages, and prices in general go up but our wages don’t. (‘A Very Careful Strike,’ 39)

Thus we have a dual-process where the ‘externalization of the home’ is coupled to what we can call the ‘externalization (or generalization) of precarity.’ In other words, if Precarias are right to conceive of precarity as a general tendency of society, it is because precarity is a process that continuously produces ever greater conditions of uncertainty for a greater number of workers; particularly with respect to their lives as conditioned by the demands of (re)production. Thus the question naturally comes about: what to do in situations such as this one? how to go on living when “we don’t know who will care for us tomorrow”? Precarias a la Deriva propose a project of “recuperating and reformulating the feminist proposal for a logic of care. A care that…in place of containment, it seeks the sustainability of life and, in place of fear…bases itself on cooperation, interdependence, the gift, and social ecology.” And in order to implement such a project, Precarias provide us with four key principles for organization and collective struggle: affective virtuosity (attempt to break the racialized and gendered sex-care-attention continuum and view each affect as an essential and creative aspect of life as a whole), interdependence (mutual aid according to the logic of the gift), transversality (refutation of any fixed and clear distinction between labour- and leisure-time), and everydayness (local instantiation of care as a form of social organization). Without distracting ourselves from the exigency of precarious life, it is helpful to highlight the fact that Precarias a la Deriva’s list of principles adopts one of Guattari’s key terms: transversality or what he sometimes calls ‘transversal connections.’ And so it is no surprise that for both Precarias and Guattari the category of transversality fundamentally means the (collective) development of ‘a political struggle on all fronts.’ Alternatively, we could use the language of Guattari and define transversality as a concrete rule for effectuating abstract revolutionary machines of desire and whose function is the coordination of various struggles taking place across the Full Body of Capital. In other words:

There is not one specific battle to be fought by workers in the factories, another by patients in the hospitals, yet another by students in the universities. As became obvious in `68, the problem of the university is not just that of the students and the teachers, but the problem of society as a whole and of how it seems the transmission of knowledge, the training of skilled workers, the desires of the mass of the people, the needs of industry and so on…[So] this dichotomy between social reproduction and the production of desire must be a target of the revolutionary struggle wherever…repression works against women, children, drug-addicts, alcoholics, homosexuals, or any other disadvantaged group. (Guattari, ‘Molecular Revolution and Class Struggle’)

- In the present, one of the fundamental biopolitical challenges consists in inventing a critique of the current organization of sex, attention, and care and a practice that, starting from those as elements inside a continuum, recombines them in order to produce new more liberatory and cooperative forms of affect, that places care in the center but without separating it from sex nor from communication.

Why is the transformation of the current order of sex-attention-care seen as a ‘biopolitical’ challenge? And what would it mean to “place” care at its center? The social transformation of situations of precarity into the means for collective emancipation is biopolitical to the extent that it emphasizes the the conditions by which every day life under capital perpetuates and sustains itself; these conditions that, with the aid of mechanisms of control, surveillance, and repression, make life ever more consistent with market demands. Thus, it is because Precarias see the task of social transformation as being waged in sites of (waged and/or unwaged) reproductive labour that ‘placing care at the center’ becomes imperative. And it is care, says Precarias, is actually the emancipatory underside to understanding what reproductive labour could become. What Precarias will go on to call a ‘careful strike’ envisions a coordinated diversity of struggles centering on sites of reproduction and organized so that those who have been historically tasked with society’s extra-socially necessary labour time can refuse to satisfy their social function without the threat of incurring some penalty, be it material, legal, social, or otherwise. As Precarias eloquently write,

[T]he strike appears to us as an everyday and multiple practice…there will be those who propose transforming public space…those who suggest organizing work stoppage in the hospital when the work conditions don’t allow the nurses to take care of themselves as they deserve, those who decide to turn off their alarm clocks, call in sick and give herself a day off as a present, and those who prefer to join others in order to say “that’s enough” to the clients that refuse to wear condoms… there will be those who oppose the deportation of miners from the “refuge” centers where they work, those dare – like the March 11th Victims’ Association (la asociación de afectados 11M) – to bring care to political debate proposing measures and refusing utilizations of the situation by political parties, those who throw the apron out the window and ask why so much cleaning? And those who join forces in order to demand that they be cared for as quadriplegics and not as “poor things” to be pitied, as people without economic resources and not as stupid people, as immigrants without papers and not as potential delinquents, as autonomous persons and not as institutionalized dependents…Because care is not a domestic question but rather a public matter and generator of conflict. (43)

5. Utopia & una huelga de mucho cuidado

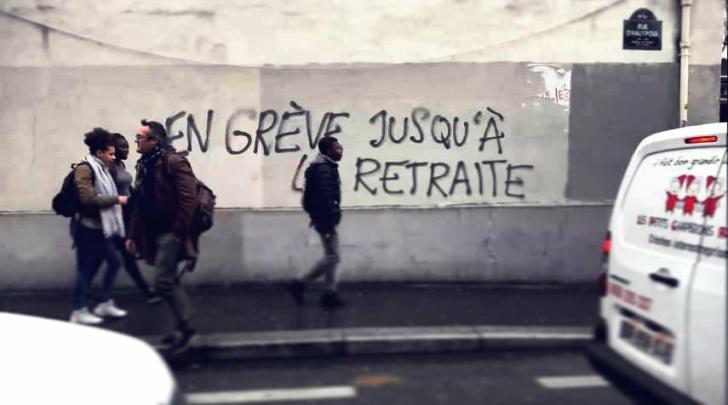

The caring strike: the means for collective struggle centered on questions historically seen as irrelevant – and precisely to the extent that they were the very conditions of possibility for the ‘relevant’ issues to be addressed. The caring strike: identifying as one’s own the problem of discovering the means of acting in concert with different and perhaps distant movements (e.g. the recent wave of teachers strikes throughout the United States, the development of the ‘social’ strike and what Precarias/Guattari would see as its transversal set of relations incarnated in their platform – though in its current form, however, these transversal relations largely exist within Western, and to a lesser extent Eastern, European countries). The caring strike: putting an end to one’s participation in a labour, which makes us strangers to one another, and is especially addressed “to the men – “are we going to end with the mystique that obliges women to care for others even at the cost of themselves and obliges men to be incapable of caring for themselves? Or are we going to cease to be sad men and women and begin to degenerate the imposed attributions of gender?”

The caring strike, then. For it is not only men, or capital and the various human forms it takes (bankers, presidents, police officers), who dream of kingdoms. Like all exhausted people, precarious workers imagine utopias of rest.

taken from here