Voices of Notara. Part 3: “a place of love and revolution”

Posted on 2019/11/24

This is one in a series of interviews with people involved in the Notara 26 squat in Exarcheia, Athens. The struggle for the free spaces here is made up of people with very different backgrounds, life stories and ideas. We aim to record people’s own words without imposing our views – though of course we can’t escape our own perspectives, or the limits of translation.

3. “Dokhtar-e-Mah” (daughter of the moon)

The idea of Notara came when lots of people were arriving in 2015. Many people were camping in the park in Pedion tou Areos, next to Exarcheia in the centre of Athens, living in tents outside in very bad conditions. We were some people from the movement who went to try and help.

Winter was coming. We held an assembly with comrades, and decided to find a building and occupy it as a squat for refugees. After doing a mapping of the area, we decided on this one, which belongs to the ministry of labour but had been abandoned for more than five years. We said – “what is public, we’ll give to the people.”

We entered the building on 25 September 2015, but we needed at least 15 days to prepare it. We made separations for rooms, showers, common spaces, storage spaces, the kitchen, etc. Social kitchens supported the project and brought in food every day for lunch and dinner, as later they also did for other squats in Exarchia.

Notara 26 was the first squat for refugees opened in Exarcheia. At least 12 or more opened after that. We had no model for how it would work, and we were testing everything out as we went. At the start, we had an assembly every day, and we set up some basic principles. We agreed that everyone would participate as individuals in the new squat, rather than representing groups to which they belonged. And we agreed a political framework based on these ideas: self-organisation, equality, horizontality, and acceptance of difference.

The term “self-organisation” was very important in the refugee solidarity movement at that moment. What does it mean for you?

It means to take our lives in our own hands. We decide together what to do, how to do it, what are our visions and how we try to achieve them. And, from the beginning, we said no connection to the state or to NGOs.

But self-organisation is difficult. Particularly at the beginning, when the borders were still open and refugees were arriving for just two or three days, so it was a squat of people in transit. You can’t really have self-organisation when people don’t stay long enough to build a community. And how can you ask people to get involved in self-organisation when maybe it’s the first time they’ve ever been allowed the right to decide for themselves?

The borders close

So that was the first period of Notara. It was a transit point for refugees passing through Greece, and the “solidarians” – mainly Greek people, and some existing refugees coming mainly as translators – were doing all the jobs.

The second period started in March 2016, when the borders were shut and the EU-Turkey deal was signed. Now people were stuck in Greece and stayed much longer in the squat. Also, a lot of comrades from all over the planet were coming to participate in the squat – and are still coming until now.

The fascist fire bomb attack

Then, on 24 August 2016, at 4 am, came the fascist attack. It was a fire bomb with gas canisters. There could have been many people killed or injured, but the three residents who were on security duty had very good reactions. One called people to come in solidarity, one took a fire extinguisher, and the third person went upstairs to wake everyone and get them down. A lot of comrades came quickly in support. Two fire trucks came, eventually they put it out at 8 am. Everything in the ground floor “salon”, and the childrens’ play area, the stores, the pharmacy, were all destroyed.

We thought the building was gone. But there was so much support, not just hands to work, but also people sending funds from other countries, and the other squats rallying round to house people. We were open again in 15 days.

The third period

There was an assembly where the refugees living in the squat said they didn’t want to be referred to as “refugees”. They wanted to be called the residents of Notara. I think this marks the beginning of a third period: when self-organisation really started, not just as a theoretical aim. People were staying longer in the squat and making a real community.

Of course there have been lots of testing times and problems. It’s a political and social project in process. I think it’s only now, after four years, that we can really call Notara a self-organised space. Decisions are mostly in the hands of residents, with solidarians who don’t live in the squat coming to offer their support. Work is carried out collectively with people forming teams for security, cleaning, storage, food distribution, supervising the playground, etc.

From the beginning until now, more than 9,000 people have been hosted in Notara, coming from more than 15 countries.

And the squat has also become a site of many projects and initiatives. We have had four convoys coming from other countries, particularly France, bringing supplies. We have had groups for women’s empowerment, language lessons, children’s activities, collective kitchens, photography, dance, theatre. One of our core principles has been the acceptance of difference, and one sign of that is that some of the first assemblies of the community of LGBTQI refugees started here.

I want to quote our first declaration, which we still say until now. It says: “let’s make the odyssey of refugees for survival the voyage of humanity towards freedom.”

What does Notara mean to you?

Notara is a place of love and revolution. Here you find many people with different cultures, different experiences, beliefs, ideas – but we are all are trying to walk together towards freedom. Without the state, without NGOs, but ourselves, together. This is revolutionary.

And love, because as a political and social project, we are not only anarchists and anti-authoritarians, we are people trying to build connections, to find things in common across our differences. We have many problems, but we continue. And that requires love. It is because we love our community that we keep working to overcome the challenges.

To continue a struggle you don’t just need fighters, you also need human relations. Otherwise you just have an army, not a revolution. What we need is – human relations with a fighting spirit.

What are your thoughts on the current situation of threat?

In July, a few days after the election, they made their first attack on us, cutting the electricity. Since then, most of the squats in Exarcheia have been evicted, and there have been numerous threats that we will be next.

During these four years, Notara 26 has been welcomed in the neighbourhood of Exarcheia and has been an active part in the life of this neighbourhood. But since the evictions of Spiro Trikoupi 17 and other squats on 26 August, we are living in occupied territory, with riot cops stationed all around us. They are here all day, all night, causing trouble and provoking us – shouting racist abuse, banging on the windows, trying to force the door, and so on – until they get the order to evict.

We have had 24 hour security watch on the squat since the fascist attack in 2016. And what is for sure, the Notara assembly took the decision that we will defend this community. We are not leaving the building. We will defend it in our own way. And they have to know that, even if they evict this building, they cannot evict the idea of Notara.

Also soon after the election, the City Plaza squat organised by left-wing groups decided to close. Amongst other things, they said it was not safe for refugees to stay in a building under intense threat. Also, no doubt many were tired after three years of the squat. Did you discuss this at Notara?

Every three or four months we have a special assembly with just the residents present, not us “solidarians”, to discuss big issues about the squat and its direction. After City Plaza left we were shocked, especially about the timing just a few days after the election, and the residents’ assembly met to discuss it. They took the decision that they wanted to continue. That’s their decision, but we solidarians are totally behind this too. We say that whatever happens, we continue.

Now, in recent weeks we have taken in more people who have been evicted from the other squats. They’ve already been through at least one eviction, and they know what may come here. But when you’ve experienced the freedom of a squat, and when you’ve experienced the hell conditions in the government camps, what do you choose?

As for being tired, of course I’m tired. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t. But speaking for myself, I can’t surrender. When I feel tired, I look to my picture of utopia, of the horizon that we’re walking towards.

How do you see the future?

The future is an open horizon. We make our road as we walk it. It is sure that Notara will never die. Even if they evict this building, they cannot evict the idea. I know that the community of residents and solidarians we have built will continue in new ways. The struggle for freedom, and our human relations – these are what give us the power to see the horizon ahead, and to walk towards it. Posted in General | Leave a reply

Voices of Notara. Part 2: “they can only kill the fear in our hearts”

Posted on 2019/11/24

This is one in a series of interviews with people involved in the Notara 26 squat in Exarcheia, Athens. The struggle for the free spaces here is made up of people with very different backgrounds, life stories and ideas. We aim to record people’s own words without imposing our views – though of course we can’t escape our own perspectives, or the limits of translation.

2. Kargar-e-sorgh (“Red Worker”)

I was a political and worker activist in Iran. In the city of Ahwaz, in the south of Iran, I was working in a big factory, a metal works, and I became active in the workers’ movement there.

You were a trade unionist?

No, not a trade union. The only trade unions in Iran are those controlled by the regime. We were organising strikes and demonstrations spontaneously, a grassroots movement. Our factory and others close to it in Ahwaz became very active. The movement was growing for about four years, and from about two years ago we had a lot of actions and demonstrations. Last October, 2018, we had 3000 workers on strike. The strike lasted for forty days, it was one of the biggest and the longest that have happened since the revolution. I was part of the coordinating group for that strike.

I was arrested on 23 October. They told me: “we’ll let you go, on condition you go back to the workers and tell them to stop the strike and agree to the bosses’ conditions.” I agreed and they released me. But then I went to the demonstration in the street and I said the opposite of what they’d told me.

“They can only kill the fear in our hearts”

I said this: “our hearts are ready for their bullets. But the cops’ bullets can’t kill us, they can only kill the fear in our hearts.”

We occupied the factory. Two days into the occupation, the police attacked people’s homes in the night and arrested 41 people. So we decided to occupy again, and this time all stay inside, not going home. The police completely surrounded us, but we held the occupation for five more days.

After those five days, some colleagues brought a van inside as if they were moving materials, they hid me in the van under the stuff and took me out. I managed to get out of Ahwaz and go into hiding. They arrested more workers from our factory, and they put a documentary on national TV accusing me of being an Arab separatist. It doesn’t matter if you’re Iranian, Kurdish, Arab, whatever, they accuse you of lies like that.

So how did you get out of Iran?

I managed to get out to Turkey, over the mountains. In Turkey again I was arrested, for having false papers, and put in prison for 50 days. I spent four months in Turkey altogether, almost half of it in prison. In Turkey I experienced a lot of racism, a lot of racist abuse because I didn’t speak Turkish.

Getting to Greece, that’s another story again. I tried three times to cross, over the land border at Evros. The first two times I was caught by Greek soldiers. They beat us up, they made us take off our clothes and threw them in the river. Then they pushed us back to Turkey.

But the thing I was most scared of? Not the Greek soldiers, but if I got caught by the Turkish soldiers again going back into their country. I was worried that if I was arrested in Turkey again then they’d deport me to Iran.

In Exarcheia

Finally, I made it. When I got to Greece, I was really scared about fascist attacks. After my experiences in Turkey and on the border, I was thinking the world is full of fascists and racists, it’s going to be just as bad in Greece. That thought was always on my mind.

Then on the second day in Athens, I came here to Exarcheia. And I thought – “wow!” Really, wow!

I didn’t know two words of the language, but no one cared. The first place I went to was K-Vox (occupied cafe and social centre). I didn’t know anyone, I just walked in to get a coffee. I could barely communicate, but people were smiling at me! I got such a good feeling. I felt – here I’m somewhere where your skin colour, your language, how you dress, doesn’t matter. In Exarcheia, I found, no one cares about those things.

Later I met a friend, a comrade I knew from Iran. He brought me here to Notara. I don’t live in Notara, I come here in solidarity. When I came here I felt in a place where people are part of a movement, a common struggle. I feel close to people here, I feel that we share ideas.

What does Notara mean for you?

This place has become very important for me. I say to people here: you can count on me for anything, even if you need someone to clean the toilets I’m ready to do it.

Then the evictions started in August and the police started making threats against Notara. When I saw people rallying around, coming out for demos, I decided to participate more. Maybe I can’t do much, but I feel it’s important to come here and show support for my friends. To help them keep up their spirits. If the police come now I could be in danger, but I don’t care. I prefer to try not to think about my personal situation, I feel happy to be close to my friends here.

Notara has been a big experience in my life. To see people living and working together like this, making a place in common, without many big problems. To see people from other countries coming to show their solidarity. To see people acting as equals, all on the same level, no matter where you come from.

The language of struggle

I am very happy if this movement accepts me and knows me as a comrade. This movement in the squats and streets of Exarchia has taught me that our fight, our struggle, doesn’t have any geographic limits, it doesn’t have any one place. All of us come from different places, we speak many languages. But we all share one language – the language of struggle. Posted in General | Leave a reply

Voices of Notara: interviews from the struggle in Exarcheia. Part 1: “Javid, the immortal”

Posted on 2019/11/24

This is one in a series of interviews with people involved in the Notara 26 squat in Exarcheia, Athens. The struggle for the free spaces here is made up of people with very different backgrounds, life stories and ideas. We aim to record people’s own words without imposing our views – though of course we can’t escape our own perspectives, or the limits of translation.

1: “Javid” (the immortal)

In my country, Afghanistan, people in my family told me – “leave Afghanistan and go to Europe. There you will find a better life for you and your child, it is safe there, and you can find a way to make a living.”

We had a very difficult journey to get here. Particularly coming from Iran to Turkey, twice we were caught by the Turkish police crossing the mountains because our baby was only a month old and started crying. It was so dark and hard walking through the mountains, the baby was so weak and tired, death was in front of our eyes. The second time, the police beat me unconscious. My wife wept and begged for them to let me go. In the end, we had to give them our money and phones to let us through.

Eventually we arrived here in Greece. We asked for help to find somewhere to live, but they told us – you must have papers, and we didn’t have papers. The only place we found that would help us was a squat, Spyro Trikoupi in Exarchia. We were there for two and a half months. Then the police came and evicted the squat. That was on 24 August.

What happened to you after Spyro Trikoupi was evicted?

They arrested us and put us in prison, in the closed prison camp of Amygdaleza. In the prison camp they told us: if you want to be released, you have to apply for asylum here in Greece. So we agreed, and signed the papers to apply to stay in Greece.

Then one night, after we’d been in the prison for 50 days, they came in the middle of the night. They put us on a bus and took us out of the camp. They drove us out of the city, to the middle of nowhere, and released us. They said: go, you are free.

We walked for 10 kilometres back to a town. We didn’t know where to go. We went to Skaramagas refugee camp and asked for a place to stay there, but they said they didn’t have room for us. We were sleeping out in the open, being eaten by the mosquitoes.

How did you come to Notara?

So, because of the time we spent in Spyro Trikoupi, I knew about Notara. We came here and asked if they could help us. Two or three days after we came here, they gave us a room to live in.

Here in Notara we have water, gas, electricity. To rent a place would cost something like 300 Euros, and we don’t have that. We get nothing from the state. They asked me to register for a cashcard, but I’m waiting and it hasn’t come. We don’t get any support from anyone, and my family in Afghanistan aren’t able to help us.

“Only the squats have been here for us”

We had an interview for our asylum case. They told us: “no, what the police told you is wrong. We need to give you a new date for an interview.” The new date is in 2022! Until then, we are stuck in this situation.

What I want to say is that the state, the charities, the NGOs, none of them have done anything for us. We’ve been round many agencies and charities. They just say: “we can’t do anything for you”. Or they say: “we’ll put you on a list”. Only the squats have been here for us.

What does Notara mean for you?

Notara is a place with people who care about other people. They especially care about our child, and the other children. Here we have meetings, assemblies, where everyone is involved, and we try to make decisions correctly, with justice.

Something that is very good: there is no nationalism here, no racism or patriotism. When we were in the prison camp all the time the police were calling to us “Taliban, Taliban, Mullah Omar”, because we come from Afghanistan. Here we are free of all that. Posted in General | Tagged athens, exarcheia, notara26, voices of notara | Leave a reply

Updates on the battle to defend Exarchia: for freedom, self-organisation and solidarity

Posted on 2019/11/13

Demo in Heraklion, Crete against evictions

The past few weeks have seen an intensification of the Nea Demokratia government’s efforts to subdue the Greek anarchist movement and crush initiatives that offer alternatives to prison society. In particular, the anarchist neighbourhood of Exarchia in Athens has been a focal point for its aggression. A rough chronology of this repression as well as actions of solidarity and resistance taken by comrades in Athens is listed below.

The current rumour is that the State wants to evict ‘all squats’ by 17th November. Another rumour puts the deadline at 6th December. Both are significant dates in the history of the Greek anarchist movement, which are marked by annual riots. What ‘all squats’ means is not entirely clear. What is clear from the past few weeks however, is that attacks have been made on squats both inside and outside Exarchia, and as well as in cities in other parts of the country.

Evictions of migrant housing squats

The State’s first focus for attack on occupied spaces has targetted the numerous squats that offered alternative housing to the dire state-run camps for migrants. These were self-managed spaces inhabited by migrants, anarchists and anti-authoritarians, often of considerable size. They were largely concentrated in Exarchia.

In August, a month after the new government came into power, cops evicted four Exarchia squats (Spirou Trikoupi 17, Transito, Rosa de Foc and Gare).

This was followed by three more evictions in September (5th School in Exarchia, the Jasmine squat in nearby Archarnon street and another one near Jasmine).

Most recently in October, they evicted another Exarchia occupation, Oniro. Residents were loaded onto buses and taken to camps; their belongings were thrown away. In all, hundreds of refugees have been removed from these self-organised spaces and taken to state run camps and prisons. There are still a few migrant housing squats still standing in Exarchia, but they remain on high alert of eviction.

Legal and policy changes

As well as evictions, serious legal and policy developments have been made which attack rebels across the country.

These include:

– The abolition of the university asylum law. This law had largely prevented the cops from entering university campuses since the 1973 uprising against the dictatorship. The uprising was centred around the Politechnic University and resulted in a massacre by state forces there. Occupied spaces have been a traditional feature of many Greek universities and key infrastructure of the country’s anarchist and anti-authoritarian movements. The law had been much contested in recent years, until it was abolished in August, which is expected to make it a lot easier for the state to evict many squats.

– The reintroduction of the ‘Delta’ cops, rebranded as DRASI (‘action’). This notorious and particularly vicious gang of biker cops was disbanded in 2015, but has been brought back by the new government and is now back on the streets.

– New laws to further criminalise resistance. For instance, a maximum 10 year prison sentence for being found in possession of a molotov, and the creation of penalties for inciting riot or illegal acts, and for making interventions in state buildings.

Brief chronology from the past few weeks

Wednesday 30th October:

Riots break out on Patission near ASOEE university in solidarity with the insurrection in Chile.

Thursday 31st October:

A student demo takes place against the abolition of the university asylum law and education reforms. Students attack cops with flagpoles.

Friday 1st November:

A demo in solidarity with the insurrection in Chile starts at the Chilean embassy and winds back to Exarchia.

Saturday 2nd November:

• Eviction of Vancouver Apartment squat in central Athens, which had been occupied for the past 13 years. The squat was on property belonging to ASOEE, the Economics and Business university.

The cops take the unusual move of doing the eviction on a Saturday, when the university is closed and many students are not around to intervene. The move also comes on the morning of a significant demo against attacks on squats and migrants, which Vancouver had been publicly supporting. During the eviction 4 comrades are arrested, while one of the cats is killed by a police dog. The other 3 cat residents are effectively buried alive as the building is then knowingly sealed with the cats trapped inside.

There are ongoing legal efforts to free the remaining cats, since a squadron of riot cops have been guarding the building and all entrances are bricked up.

• The same morning, some of the riot cops permanently stationed around Exarchia attempt to smash down the door of Notara, one of the largest and few remaining migrant squats in Athens. This follows threats and insults which were shouted by cops in the preceding days, including shouting “Raus!” (reference to ‘Juden Raus’ a phrase used by Nazis meaning ‘Jews out’).

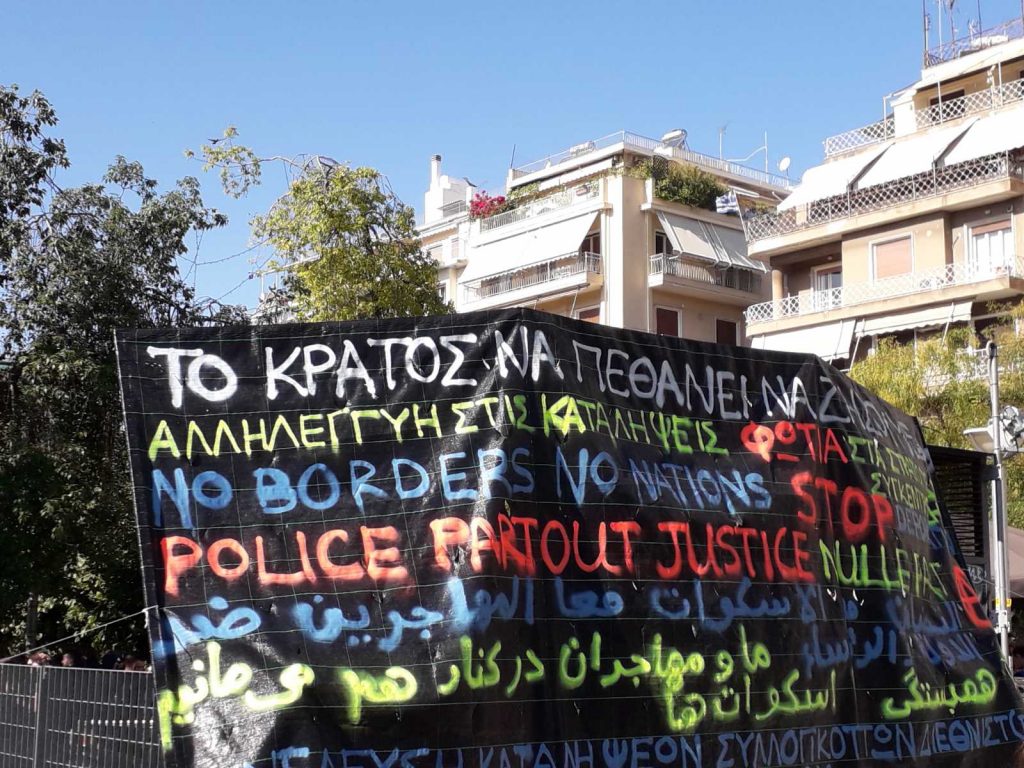

• A demo of around 1000 people takes place in solidarity with migrants & in defence of squats and self-organised spaces, called by the open assembly of squats, migrants, internationalists and solidarians. The demo winds through migrant neighbourhoods and is characterised by multilingual banners, leaflets, stencils and chants. Following the demo, there are molotov attacks on the police in Exarchia as an immediate response to the eviction of Vancouver. The police respond with teargas and flashbangs, and two people are arrested at random in the neighbourhood.

• In the migrant prison of Petrou Ralli, Athens, 16 female detainees start a hunger and thirst strike for their release and transfer back to the islands

Monday 4th November:

• Another student demo takes place in central Athens. Students attack the cops with molotovs and the police fire tear gas.

• The media reports that riot cops are attacked on three separate occasions in different locations throughout the day.

Tuesday 5th November:

Palmares squat is evicted in Larissa, central Greece. 16 people are arrested.

Wednesday 6th November:

• Several hundred people protest in solidarity with Notara squat, a prominent migrant squat in Exarchia that is home to up to 100 refugees, including many kids, and is under threat of immediate eviction. Notara is a large building that has been occupied since 2015.

Thursday 7th November:

• Clashes with the police take place in Exarchia which results in damage to one cop’s bike and the cop being sent to hospital. The police then rampage through Exarchia and besiege people in a popular cafe. 16 people are reported arrested.

Friday 8th November:

• Attack on Libertatia squat in Thessaloniki. Libertatia was significantly burnt down after being firebombed by fascists in 2018. At least four people are arrested.

Saturday 9th November:

• Police carry out an operation which results in (according to the media) searches on 13 homes and the detention of 15 people, 3 of which end up with charges. The press reports that it is an ‘anti-terrorist’ operation related to historical incidents and that weapons have been seized. Numerous people report being followed, harassed or raided by anti-terror cops.

• A demo in central Athens in defence of squats called by No Pasaran assembly is attended by hundreds of people.

Sunday 10th November:

• Dozens of people hold a demo in solidarity with the Petrou Ralli hunger strikers at the migrant prison, shouting slogans in different languages for the detainees.

• The polce raid ASOEE, the university of economics and business, and evict a steki. Images of seized helmets, sticks and bottles are shared widely by the media and used as a pretext by the academic council to shut down the university until 17th November.

Monday 11th November:

• A group of around 100 leftists break the lockout and enter the university. The police enter the premises, attacking people, firing gas and besieging the group of students. A stand off ensues as a crowd of many hundreds gathered on the busy road outside, forcing its partial closure. The police eventually leave, and a spontaneous march of 1000+ students follows.

• Some people are arrested during the siege. One of the students who was apparently outside ASOEE during the clashes was later arrested outside his home and his house was raided.

Tuesday 12th November:

• Police evict Bouboulinas squat in Exarchia, home to dozens of refugees. They are initially taken to Petrou Ralli detention centre, where a solidarity demo is held outside. Most are then bussed off to Amygdaleza migrant camp, but many occupants refuse to get off the buses. Some of the residents of Bouboulinas resist attempts to be split up and divided into ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ migrants.

• At a solidarity gathering at court for arrestees, the cops fire tear gas and flashbangs in an unprovoked attack.

• A demo winds through the residential neighbourhood of Kypseli in defence of squats and against the state repression. The demo is called by Lelas Karagianni 37 squat which has been occupied for 31 years. —————— Needless to say, acts of international solidarity would be very welcome. Developments continue to unfold quickly. For further updates see https://athens.indymedia.org or for frequent English updates check out @exiledarizona on Twitter.

Evictions in August

Eviction of migrant squats

Chile solidarity riots

Chile Solidarity riots

Chile solidarity riots

Vancouver squat, post-eviction

2nd November demo

Multilingual slogans on 2nd November demo

Attack on the cops in Exarchia following Vancouver eviction

Cop bike following clashes in Exarchia on 7th November

Encircled at ASOEE

Lelas Karagianni demo on 12th November

taken from here