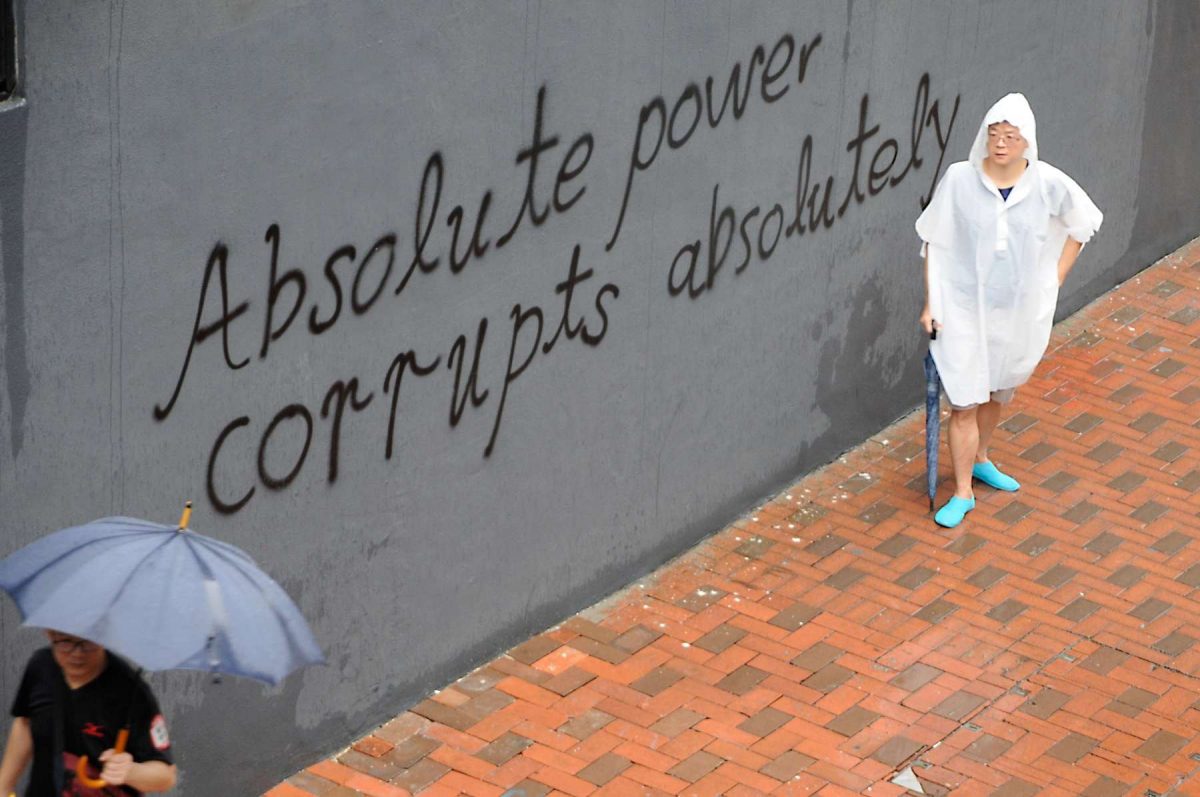

The Hong Kong government is so far mainly using repressive measures against the mass movement, but, recently, state media in China have started pushing for a change in the city’s housing policy – possibly a first sign for economic concessions in reaction to the pressure ‘from below.’

The Hong Kong economy, already hit by the trade war between China and the U.S., feels the effects of the protest movement.[1] In recent months, real estate prices have gone down,[2] retail sales fell as well as the number of tourists (leading to lower numbers of travelers at the airport,[3] falling hotel occupancy rates and prices, and more),[4] the transshipment volume of goods from China has declined,[5] the stock market has performed badly, and the rating agency Moody’s has downgraded Hong Kong citing “the rising risk that the ongoing protests reveal an erosion in the strength of Hong Kong’s institutions […] and undermine Hong Kong’s credit fundamentals by damaging its attractiveness as a trade and financial hub.”[6] Subway stations of the MTR have been closed down several times, in early October even all lines, disrupting the commute of many employees, and several shopping malls and many shops had to be closed during or after clashes.

All in all, the rebellious movement in Hong Kong hampers the development of the economy, and it also puts in question the city’s status as a financial hub for China’s capital imports and exports. The CCP regime still has an interest in keeping that status while avoiding any political reforms or granting any ‘autonomy’ to the city. So how does it want to get a hold of the confrontation in Hong Kong?

Actually, there are some similarities with social struggles in mainland China. First of all, there is an absence of formal leaders, representatives, or organizations the regime could talk to in order to ‘make a deal.’ In mainland China, any formal leadership or organization that is not in the hands of the CCP is repressed. The regime can just use forms of repression and concession and hope they work to calm down social discontent. In Hong Kong, the movement decided to have no formal leaders or organization for fear of repression (as during and after the 2014 Umbrella Movement).

This is a dilemma now for the Hong Kong government and the CCP regime, because without negotiations with a legitimated body of protester leaders or organizations and an agreement of some kind,[7] the are just left with two one-sided measures: repression and/or economic concession(s).

Repression has been the main measure used in Hong Kong – as well as in China – so far, except for the conceded withdrawal of the extradition bill (a minor concession if we consider what is at stake by now).

Economic concessions and a possible material improvement of living conditions is what the CCP regime has offered in reaction to social struggles like strikes in mainland China. While strike organizers and groups supporting workers’ struggles are tightly controlled, get arrested, and get punished when seen as a threat, the CCP regime has permitted and even orchestrated certain wage increases and other improvements, for instance, for the hundreds of millions of migrant workers – at least, until a few years ago when the economic slowdown limited the regime’s willingness and ability to make substantial economic concessions.

Regarding Hong Kong, Chinese state media has, in fact, recently started to criticize the role of Hong Kong’s wealthy real estate tycoons,[8] and the Hong Kong government actually discussed a change in its housing policies.[9][10]

Rents – and the huge gap between incomes and housing costs in the city – are one of the reasons why many people in Hong Kong are dissatisfied with their situation and the political system. An attack on the tycoons and their family businesses which control large parts of the Hong Kong economy would be a big change as the tycoons have so far collaborated with pro-Beijing political forces in the city and the CCP leadership itself.[11]

It is important to note that the movement in Hong Kong produces considerable pressure ‘from below’ that might lead to economic concessions. However, even if the CCP regime does take decisive steps and forces the Hong Kong government to introduce more social housing policies in Hong Kong, it would probably take years to deliver any improvements for the people in the city.

Whether such concessions would lead to political submission (as intended by the CCP regime) is doubtful anyhow.[12]

Die Regierung Hongkongs setzt bisher vor allem auf repressive Maßnahmen gegen die Massenbewegung, aber kürzlich haben chinesische Staatsmedien begonnen, eine Änderung der Wohnungspolitik der Stadt zu fordern – möglicherweise ein erstes Zeichen für wirtschaftliche Zugeständnisse in Reaktion auf den Druck ‚von unten‘.

Die Wirtschaft Hongkongs, bereits durch den Handelskrieg zwischen China und den USA angeschlagen, spürt die Auswirkungen der Protestbewegung.[1] In den letzten Monaten sind die Immobilienpreise gefallen,[2] ebenso die Einzelhandelsumsätze und die Zahl von Tourist*innen (was zu weniger Passagieren an den Flughäfen führte,[3] einer geringeren Auslastung und fallenden Preisen in Hotels usw.),[4] das durchgehende Frachtaufkommen aus China ist zurückgegangen,[5] die Börse hat sich schlecht entwickelt und die Ratingagentur Moody‘s hat Hongkong heruntergestuft mit Hinweis auf „das steigende Risiko, dass die andauernden Proteste eine Erosion der Stärke der Institutionen von Hongkong offenbaren […] und die Kreditgrundlagen Hongkongs untergraben, indem sie die Anziehungskraft der Stadt als Handels- und Finanzdrehscheibe beeinträchtigen“.[6] U-Bahnstationen der MTR wurden mehrmals geschlossen, Anfang Oktober gar alle Linien, was das Pendeln der Beschäftigten störte, und etliche Einkaufszentren und viele Geschäfte mussten während oder nach Zusammenstößen schließen.

Alles in allem schädigt die rebellische Bewegung in Hongkong die Entwicklung der Wirtschaft, und sie stellt auch den Status der Stadt als finanzielle Drehscheibe für Kapitalimporte und -exporte Chinas in Frage. Das KPCh-Regime will jenen Status immer noch erhalten, gleichzeitig jedoch irgendwelche politischen Reformen oder das Zugeständnis einer ‚Autonomie‘ der Stadt vermeiden. Wie will es also die Konfrontation in Hongkong in den Griff kriegen?

In der Tat gibt es einige Ähnlichkeiten mit sozialen Kämpfen in China. Zunächst gibt es keine formalen Anführer, Vertreter oder Organisationen, mit denen das Regime sprechen könnte, um ‚einen Deal zu machen‘. In China wird jede formale Führung oder Organisation, die sich nicht von der KPCh kontrollieren lässt, unterdrückt. Das Regime kann lediglich Formen von Repression und Zugeständnissen anwenden und hoffen, dass sie funktionieren und die soziale Unruhe befrieden. In Hongkong entschied die Bewegung, keine formalen Anführer oder Organisationen zu haben aus Angst vor Repression (wie während und nach der Regenschirmbewegung 2014).

Dies ist ein Dilemma für die Regierung Hongkongs und das KPCh-Regime, weil ohne Verhandlungen mit einer legitimierten Vertretung von Protestanführern oder Organisationen[7] und eine irgendwie geartete Vereinbarung bleiben ihnen nur zwei einseitige Maßnahmen: Repression und/oder wirtschaftliche Zugeständnisse.

Repression ist in Hongkong – wie in China – bisher die wichtigste

Maßnahme gewesen, abgesehen von der zugestandenen Rücknahme des

Auslieferungsgesetzes (ein geringfügiges Zugeständnis, wenn wir

bedenken, was mittlerweile auf dem Spiel steht).

Wirtschaftliche Zugeständnisse und die Verbesserung der

Lebensbedingungen hat das KPCh-Regime bei sozialen Kämpfen wie Streiks

in China mitunter angeboten. Während Streikorganisator*innen und

Gruppen, die Arbeiterkämpfe unterstützen, streng kontrolliert, verhaftet

und bestraft werden, wenn sie als Bedrohung gesehen werden, hat das

KPCh-Regime Lohnerhöhungen und andere Verbesserungen erlaubt oder gar

eingefädelt, zum Beispiel für die Hunderte Millionen

Arbeitsmigrant*innen – wenigstens bis vor ein paar Jahren, als das

wirtschaftliche Abbremsen die Bereitschaft und die Fähigkeit des

Regimes, wesentliche wirtschaftliche Zugeständnisse zu machen,

einschränkte.

In Bezug auf Hongkong haben chinesische Staatsmedien in der Tat kürzlich begonnen, die Rolle der reichen Immobilienmagnate Hongkongs zu kritisieren,[8] und die Regierung Hongkongs hat tatsächlich über eine Änderung seiner Wohnungsbaupolitik gesprochen.[9][10]

Die Mieten – und die immense Lücke zwischen Einkommen und Wohnkosten in der Stadt – sind einer der Gründe, warum so viele Menschen in Hongkong mit ihrer Situation und dem politischen System unzufrieden sind. Ein Angriff auf die Magnate und ihre Familienunternehmen, die große Teile der Wirtschaft in Hongkong kontrollieren, wäre eine große Veränderung, denn die Magnate haben bisher mit den politischen pro-Beijing Kräften der Stadt und der KPCh-Führung selbst kollaboriert.[11]

Es ist wichtig festzuhalten, dass die Bewegung in Hongkong einigen Druck ‚von unten‘ produziert, der eventuell zu wirtschaftlichen Zugeständnissen führen kann. Selbst wenn das KPCh-Regime allerdings entscheidende Schritte unternehmen und die Regierung Hongkongs zwingen sollte, eine sozialere Wohnungspolitik zu betreiben, würde es wahrscheinlich Jahre dauern, bevor die Menschen in der Stadt in den Genuss irgendwelcher Verbesserungen kämen.

Ob solche Zugeständnisse zu politischer Unterwerfung führen würden (wie vom KPCh-Regime erwartet), ist ohnehin zu bezweifeln.[12]

taken from here