Response to Climate Leviathan

Who will decide on climate change? Who, that is, will declare a global “climate emergency,” thereby instituting the exceptional political measures necessary to subdue the otherwise unabated, planetary ecological catastrophe of our time? Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright have proposed one answer, a vision from the future of a dramatically expanded capitalist state which assumes the entire earth as its dominion, governing all of its human and nonhuman inhabitants together in a single body politic. They dub this figure “Climate Leviathan,” and in their recent book of the same name they elaborate the possible conditions of emergence of this new political paradigm, one which would finally confront planetary climate change, if only for the sole sake of securing the profits of “capitalist elites” amidst ever-swelling ecological crises.1 If Hobbes theorized the modern state he dubbed Leviathan as the coming resolution to his own interregnum, Mann and Wainwright regard Climate Leviathan in an analogous way—that is, as a coming synthesis of rule and law from out of the political uncertainty of the present. Unlike Hobbes, of course, the point is not to thus welcome the arrival of Climate Leviathan but to anticipate the development of this new paradigm in order to inoculate the movement for global climate justice against it.

And, while Climate Leviathan is certainly not the most desirable response, it remains for Mann and Wainwright the most likely. Indeed, its world-historical momentum means there has become less and less room for grasping, much less actualizing, any political alternative. It is precisely this weakness, the fragility in pursuing anything else, which characterizes the preferred path they lay out at the end of the book: what they call “Climate X.” Left deliberately vague, Mann and Wainwright use this “X” not so much as a positive prescription as they do a meager (if nevertheless insistent) refusal of the otherwise overwhelming dictums of state sovereignty and capitalism which characterize their would-be Climate Leviathan. Aside from brief gestures to the Marxist tradition and to Indigenous struggle, their only tangible suggestion is that Climate X keep open the possibility of three “ideals” to which Climate Leviathan remains irreparably external and opposed: equality, dignity, and solidarity.

All three are certainly agreeable principles. But what is troubling is the extent to which their real, concrete practice is, in my view, not opened up but limited by this name of X. Now, I presume that the authors think that by leaving X indefinitely open they are sparing it from the possibility of errant cooptation by the liberal-democratic order it is supposed to supersede—an order which, one should recall, has routinely dressed itself in these very same principles since its inception, however abstractly and contradictorily. In the very name of X, these ideals are intimated neither less abstractly nor less contradictorily than in that paradigm which it refuses. X, put bluntly, seems to me but another call for a radical pluralism (“worldly and open, and affirms the autonomous dignity of all”) already quite familiar to ‘radical’ scholarship since the wake of the New Left. In this latest rendition, however, the call is so weakly defined that I fear it cannot withstand the blows of the twin concepts of capitalism and sovereignty to which it responds.

That is to say, precisely in the name of Leviathan, in this totalizing image of “the political,” the co-authors have made their “conjunctural analysis” of the present so overburdened as to leave any meaningful resistance to it literally ineffable. And, indeed, they seem to be well aware of this predicament—as Wainwright has recently put it, the proposed escape to an anti-sovereign, anti-capitalist Climate X is “aporetic”:

To restate it differently, on one hand we know that we must tackle the climate crisis on the existing terrain of the political, but on the other hand we know that that will not work, that we should have to transform that terrain to have any hope of addressing climate in a just fashion. We are oscillating within that aporia and we don’t know the way out.2

In my view, if Climate X is “aporetic,” it has less to do with the “existing terrain of the political” than how the abstract and indeterminate positing of X undermines the entirely determinate possibility of its own guiding principles. Real solidarity already exists, and, unlike X, it always has a name. In fact, it has many names, names which can be referenced, depended upon, held accountable. Real solidarity is grounded neither in “utopia” nor “aporia” but only ever in the determinate and, as I want to insist on here, universal conditions of our shared planetary existence.

I develop this thought below as a comradely response to this deeply provocative and important argument from Mann and Wainwright. First, however, I want to tarry with this apparent “aporia,” which seems for them to signify the impossibility of doing what must be done for climate justice, hence the necessarily “utopian” and presently indeterminate condition of escape. As for me, it rings in my ears like an unresolved (but not irresolvable) dissonance between Leviathan and X, a phase-shift which, I again want to suggest, is an artifact not at all inherent to their object of critique (capitalist society) but, more precisely, to the fraught concepts they use to analyze it. In truth, Climate X is already quite sufficiently determinate, far more than Mann and Wainwright let on, and its apparent “impossibility” is little more than a reflection of the dead-end of the political philosophy of sovereignty which so captivates it.

God, Beast, Sovereign

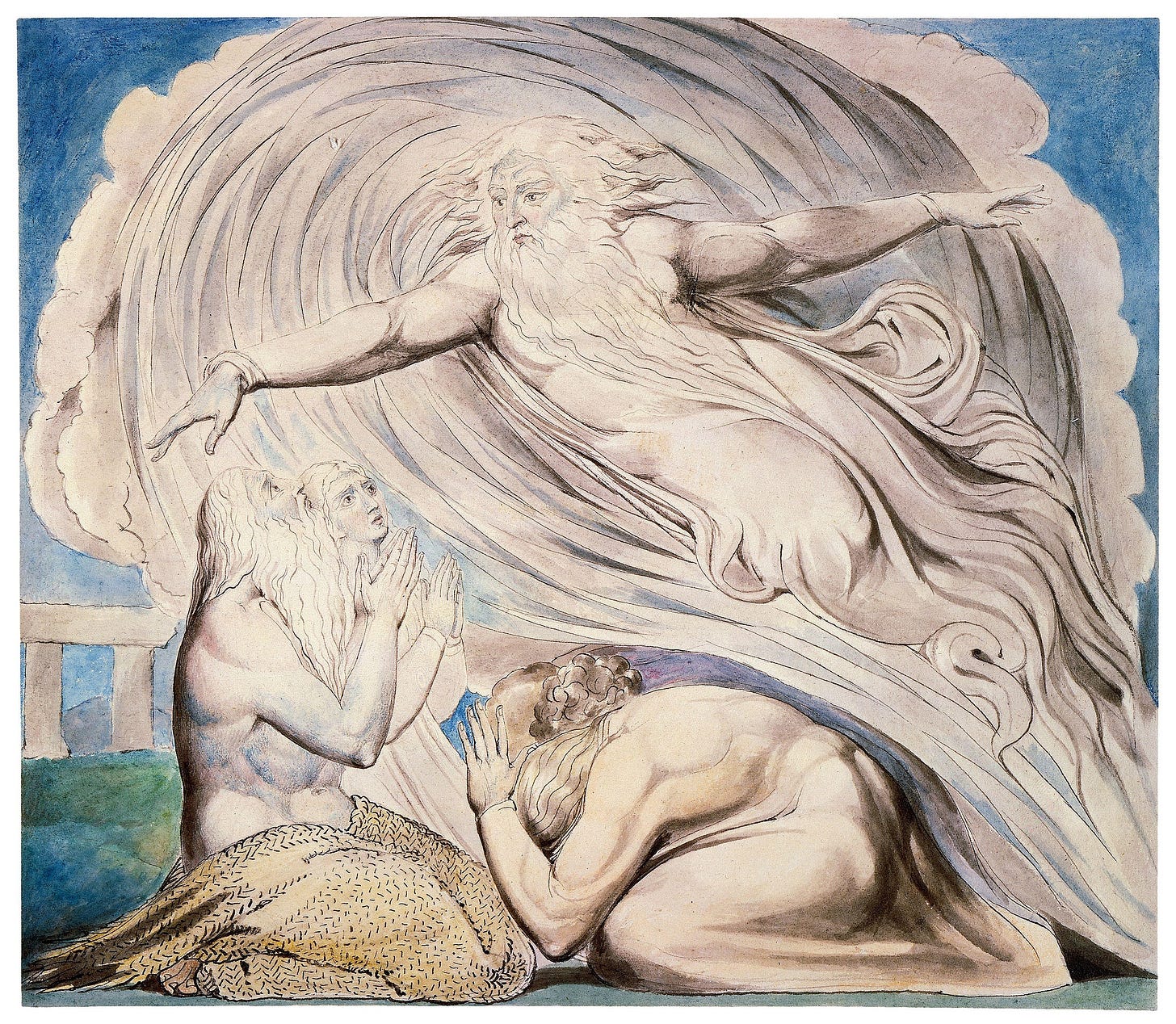

The Lord Answering Job out of the Whirlwind

Man is neither angel nor beast, and the misery of it is that whoever tries to act the angel acts the beast.

-Blaise Pascal, Pensées No. 5573

Let us first turn to this Leviathan of Climate Leviathan, a creature left curiously underexplored in the book. Now, Mann and Wainwright note early on the peculiarity of Hobbes’s use of this sea creature to personify sovereignty. While there are a number of ancient references to the serpent, perhaps its most common image stems from the Book of Job, which is explicitly cited on the frontispiece of Hobbes’s eponymous treatise. Above a crowned, anthropomorphic colossus—its massive body composed of men, arms outstretched over its domain, a sword in one hand and a crosier in the other—there is the quote: “Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei. lob 41.24” (“There is no power on earth to be compared to him. Job 41.24”).4

As the reader might recall, this reference to Leviathan is lifted from a monologue God delivers to Job. The latter was a righteous man who had been blessed with great wealth, and God was so confident in his devotion that He allowed the Devil to put it to the test. The Devil took away Job’s children, his health, and his livelihood. The experience of his suffering makes Job curse the day he was born and, later commiserating among friends, he proceeds to question what reason there could be for his recent misfortunes. At that moment, a storm breaks above him from which God responds, neither justifying Job’s suffering nor explaining his wager with the Devil but simply reminding Job of His omnipotence. Early in Climate Leviathan, Mann and Wainwright quote a key passage from this monologue:

Can you pull in the Leviathan with a fishhook or tie down his tongue with a rope?

Can you put a cord through his nose or pierce his jaw with a hook?

Will he keep begging you for mercy? Will he speak to you with gentle words? […]

Any hope of subduing it is false; the mere sight of it is overpowering.

No one is fierce enough to rouse it. Who then is able to stand against me?

Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

Everything under heaven belongs to me. (Job 41:1-11 [NIV])

Despite the profound, millennia-long diversity of interpretations of the Book of Job, Mann and Wainwright choose to rather simply follow Carl Schmitt’s philology in suggesting that Hobbes’ Leviathan has “not been derived from mythical speculations.”5 On the contrary, the modern Leviathan posed by Hobbes appears to all three neither as Nature nor God but rather as something like their shared antithesis. Sovereignty provides humans a “means to escape the state of nature,” that is, in the transference of the natural right of violence to a singular person who embodies it positively (i.e. by social contract) and absolutely.6 The human animal is then dissociated from the sovereign-subject relation and abandoned to the multitude: the unorganized, “dissolved” masses, or in other words, the urban poor. To be sure, then, the human animal does not vanish with the emergence of the sovereign-subject but endures in the city, perennially threatening it with a return to the state of nature, famously expressed by Hobbes a war of “all against all,” that is, civil war.

And so, after this early and brief remark, Mann and Wainwright rather abruptly seal the mystery of Leviathan in the philology of Schmitt. In Schmitt’s hands, this mythical sea monster becomes yet another “secularized concept” of modern political philosophy, which allowed Hobbes, with the English Civil War hanging heavily over his own life, to break from transcendental contemplation of Being and really “confront medieval pluralism with the rational unity of a rational centralized state.”7 Neither God nor Nature, then, Schmitt’s Hobbes reconstructs Leviathan as homo artificalis, a “huge machine” shedding any prior theological significance.8

However, an alternative reading of Leviathan is available: the one proposed by Jacques Derrida in The Beast and the Sovereign. Here, different questions and different stakes for modern sovereignty will be proposed. First, it appears critical for Derrida that Hobbes’s invocation of Leviathan not be simply left to the custody of the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt. For Derrida, the prosthetic, supplementary nature of Hobbes’s Leviathan requires much more penetrative and elaborate investigation. In spite of this apparently “rational” solution, namely, to 17th-century civil strife in England, the mystery of the source of the legitimacy of law in the figure of Leviathan remains aporetic: how is it possible that a covenant between God and man, the universal and the particular, be posited as a “social contract” between human and human? How is it that Leviathan becomes for Hobbes a paradoxically absolutist yet also human creation, of “which no power on earth can be compared”? And, moreover, how does not God but more acutely His cherished beast, as metaphor for primordial Nature, become an image of modern sovereignty?

For their part, Mann and Wainwright presuppose, but do not explain, this aporetic possibility of transcendence-in-immanence in order to be able to posit the adaptation of absolutist sovereignty to the climate-changing contours of “the political.” And of course, much as they do with the notion of sovereignty, the co-authors inherit this concept of “the political” from Schmitt, while again adding to it a number of crucial alterations.

For Schmitt, we should first recall, “the political” concerns the realm of pure decision which all law necessarily presupposes. It is in this realm that force grounds the law, i.e. in its outside and in existential enmity against which it guarantees the protection of its subjects. Rightly, I think, Mann and Wainwright find this notion of the political untenable. The realm of “pure decision” is for them clearly a fiction. The authors find at this point the work of Antonio Gramsci as the necessary means by which they will distance themselves from Schmittian and Agambenian readings of “the political.” Following the Italian Marxist, they deem “the political” to be the real outcome of a struggle immanent to natural history, that is, the “product of nature and humanity actively producing the world.”9

Thus, neither in the mystified realm of “decision,” nor for that matter in Agamben’s messianic time, but only from the concrete perspective of our present conjuncture, in the historical context of struggles which made it determinate and necessary, can one find the conceptual means to disclose the contours of “the political.” Leviathan does not seem to mind its “illegitimacy,” after all, and to treat its revelation, as Agamben has done, as the essential premise of political action is to turn oneself away from the much more difficult work of rearticulating the changing shape of sovereignty, such that one might anticipate and counteract its movements.10

In this way, then, Climate Leviathan shifts through Schmitt, Agamben, and Gramsci with a great deal of finesse, and the co-authors’ study of sovereignty from the perspective of natural history provides for an important analysis of hegemony in the politics of climate change. Yet, with weary eyes so fixated on Leviathan, Mann and Wainwright seem to forget what was so disastrous about treating modern sovereignty as signpost of the political in the first place.

Let us return again to the mystery of the “secularized” animality which Hobbes’s Leviathan, at least in the care of Schmitt, claims to subdue and exclude from the polis—the animality which, again, Mann and Wainwright abruptly dismiss, only to obscurely return to it in their reconstruction of the political through a Gramscian notion of natural history. Here, then, let me also reiterate the question I raised above: why is it that sovereignty recalls animality, even as it proclaims through positive reason its supremacy above and against natural right?

In his first lecture on the “The Beast and the Sovereign,” Jacques Derrida finds a provisional answer in the Introduction to Leviathan: “Art goes yet further, imitating that Rationall and most excellent work of Nature, Man. For by art is created that great ʟᴇᴠɪᴀᴛʜᴀɴ, called a ᴄᴏᴍᴍᴏɴ-ᴡᴇᴀʟᴛʜ, or sᴛᴀᴛᴇ.”11 The Leviathan is not simply antithetical to Nature, a means to escape it, but in some way its prosthetic repetition, its own self-objectification, qua art (tekhne). An “Aritificiall Soul,” then, Hobbes’s sovereign is not simply some “machinic antimonster,” as Mann and Wainwright interpret it through Schmitt, but precisely for this reason also an imitation of the “living creature that produces it. Which means that, paradoxically, this political discourse of Hobbes’s is vitalist, organicist, finalist, and mechanicist.”12

We can see here that Hobbes’s Leviathan is not as far removed from Job as it first appeared. Just as in the Book of Job, Hobbes’s Leviathan is premised on this double exclusion: not only of God as the ground of law, but also of beasts such as the mythical Leviathan, who cannot be made to answer, to submit, or to agree to the law. Two figures who cannot and must not speak the language of the law. Two figures who cannot respond or be held responsible, comprising in this way a “metonymic congruity” with the sovereign, who then stands in as the secular representation of God and the human (or perhaps more appropriate, non-animal) representation of beasts.

As Derrida explains, if we may concede the silence of God—whether or not it is necessary to presuppose, the ground is constitutively unable to speak—that animals are excluded from human convention is simply false.13 Humans enter into all sorts of agreements and disagreements, “acquired by learning and experience,” with animals and with non-human nature. This includes not only things like animal husbandry but a variety of non-human relations absolutely essential to human livelihood: forests scrubbing the atmosphere of carbon, wetlands filtering and storing floodwaters, algae regulating marine life, birds, bees, and wind pollinating the earth across vast distances, and so on. And this simple fact of the necessary, indispensable conventions we constantly enter into with non-humans also reminds us of the fact that humans enter into conventions with other humans which are neither rational nor contractual nor linguistic, and which are therefore improper to the body politic but nevertheless persist and flourish everywhere within it.

In either case, then, this notion of sovereignty, what is “proper to man,” appears to Derrida as a “brutally false” problematic which violently excludes “the animal” from the history of law, because the animal apparently cannot respond, even as it already does. And it is precisely this paradox which leads to the disastrous situation where, by objectifying man above himself, that is, by imitating the universal absolutism of God, the sovereign is forced to draw on and mimic the natural precisely through the accidental particularities and contingencies of living reality he claimed to have purified from the law. He is forced, in a word, to play the beast—not only in the brutishness of “pure violence” but in its terror, its irresponsibility, its senselessness.

If, then, we have finally found out how this figure of Leviathan—which remains a double-image, both of a “mortall God” and of Creation, of primordial Nature—comes to designate a relation between humans, this nevertheless raises for us a new set of questions: Why must we be condemned to unveil “the political” through this “brutally false” problematic? Why must the political—even the political of “natural history”—respond to sovereignty at all? Why must it be given irremediably to a questioning concerning “decisions” and “exceptions”? Who insists on this frame of the political?

Surely it is not ‘Nature,’ which had been excluded from this problematic from the very beginning. Surely also it is not the human ‘as such,’ the inscription of which has never been a singular, absolute, or personal decision—despite what the notion of the “Anthropocene” might try to tell us. And, last, surely it is neither “the people” nor any subject of history who has decided it is modern sovereignty which is ultimately at stake (a notion not to be confused with self-determination). What Mann and Wainwright call “modern sovereignty” is a curious artifact of Western political philosophy, and, as we saw with Derrida, not a particularly felicitous one at that. It is much less powerful than Hobbes, Schmitt, Mann, or Wainwright claim it to be (as an aside, this is also in my view the entire lesson of Walter Benjamin’s eighth thesis).

This is not to say that the ideology of modern sovereignty does not, insofar as it pertains to a specific mode of reasoning about the political, inform real, brutally real forces in the world, only that it need not (and should not) determine our own political commitments. And, while the suggestion of “Climate X” is precisely the gesture Mann and Wainwright make to escape from the paradigm of sovereignty, it is an “impossible” non-answer precisely insofar as it remains shaped by what it rejects. It is to this non-answer we must now turn our attention.

Critique of “Communist Metaphysics”

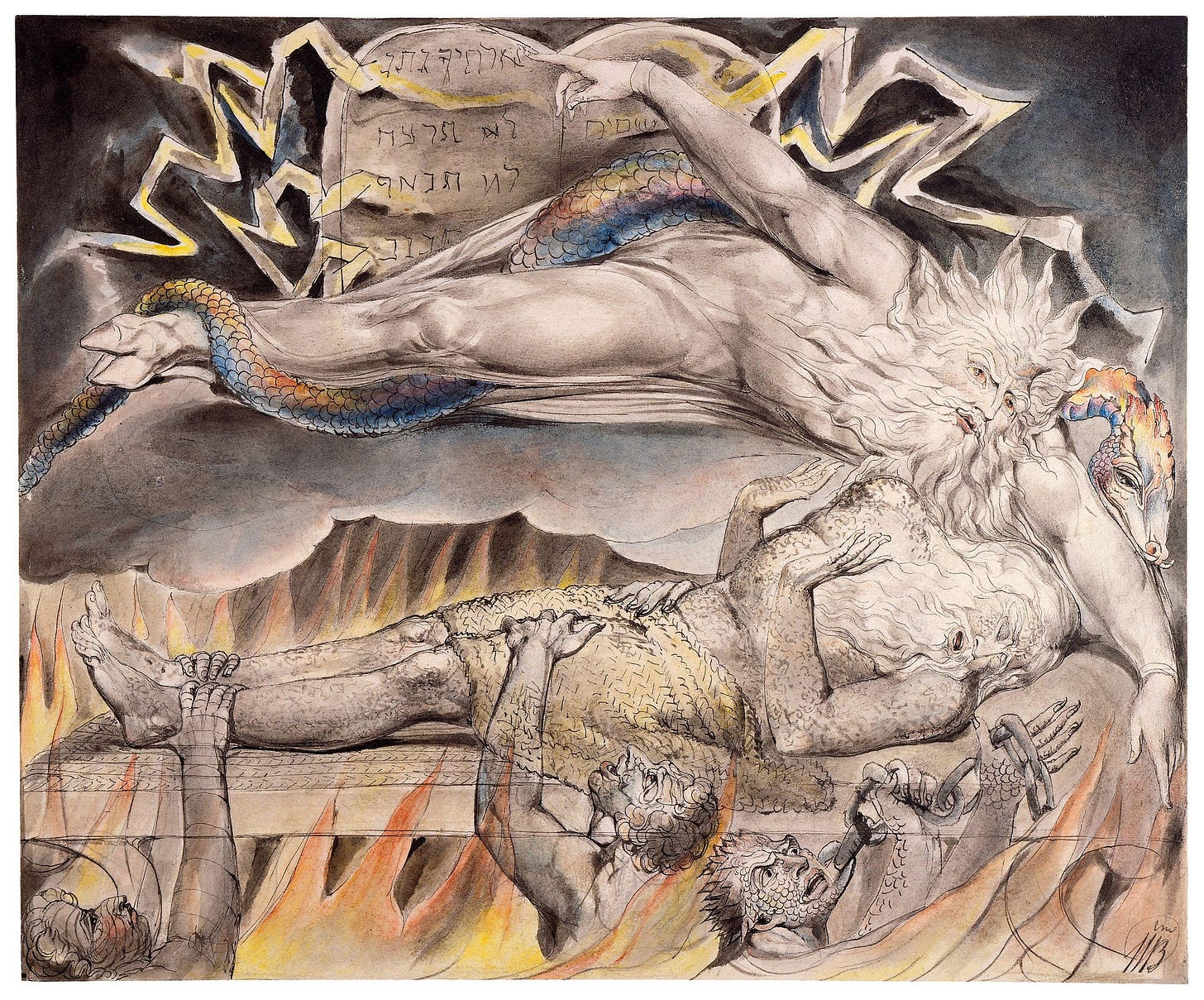

Job’s Evil Dreams

To criticise power is one thing, to put it in crisis is another.

-Mario Tronti, Workers and Capital14

There is an (almost) absence in Climate Leviathan even more curious than the lack of any sustained investigation of its central mascot. I am referring to the missing theorist from which “X” is most clearly and most closely derived: the Marxist philosopher Kojin Karatani. This connection shows up in a single footnote, which describes the “analysis of X” as “indebted” to him. And yet, despite this debt, Karatani is cited by name in the main text exactly once, in an obscure but quite illuminating reference to his interpretation of Kantian cosmopolitanism (a reference which, as it happens, will prove decisive for the argument I build out in this section). In this passage, Mann and Wainwright cite him as someone “who understands Kant to be far more radical than he is usually taken to be,”15 knowing Kant to be

fully aware of the deep-seated violence in human nature, which he called ‘unsocial sociability.’ At the same time, he believes that this violence could ultimately be contained […] According to Kant, the federation of states, and subsequently a world republic, will be brought about not by human goodwill and intelligence but through ‘unsocial sociability’ and war.16

Borrowing from Karatani, Mann and Wainwright understand Kant’s theory of cosmopolitanism as a federation of republican states supposed to surpass the “existing liberal world order.”17 This is because Kant appears, particularly in “On Perpetual Peace,” to reject the abstraction of human worth into the form of value, calling money the “most reliable instrument of war.”18 Opposed to this notion, Kant envisions the “universal community” as the speculative realization of another ideal, whereby ‘men’ are treated not as means of equivalence but as ends in themselves.

Wainwright’s 2012 interview with Karatani provides a bit more clarity about the Kantian inflection of the debt of Mann and Wainwright owed to the former in their own positing of Climate X.19 According to Karatani, by the time Marx was writing the drafts of Capital, he had embarked on a critical return to Kant. Importantly, this was (again, according to Karatani) a means by which Marx displaced himself from the speculative idealism of Hegel; and it is this move back to Kant that the critique of political economy becomes, for Karatani, the basis for a “communist metaphysics.” This communist metaphysics, as Karatani hints at most prominently in The Structure of World History, would ground not simply the transformation of relations of production but moreover the objectification of a particular mode of exchange which transcends the current capitalist world-order.20

A brief sketch of Karatani’s analysis of exchange will prove useful here. Directly corresponding to the “four quadrants” which anchor Climate Leviathan (Leviathan, Mao, Behemoth, and X), Karatani details four quadrants which he uses to schematize four possible modes of exchange (gift-reciprocity, plunder-redistribution, commodity, and X). Two axes organize these quadrants in a directly analogous way to those used in Climate Leviathan: reciprocal/non-reciprocal and free/unfree to that of Mann and Wainwright’s sovereign/non-sovereign and capitalist/non-capitalist.

The first mode of exchange (A) is, again, what Karatani calls gift-reciprocity. Gift exchange, Karatani writes, stabilizes social relations both within and between communities. But, importantly, it is also inherently coercive. Drawing on Marcel Mauss’ study of potlatch, Karatani emphasizes that, in such a situation, one cannot simply accept (nor refuse) a gift but is obliged to reciprocate, else risk a destruction of their social rank or, worse, internecine strife. In this way, mode of exchange A is thus reciprocal, wherein there is mutual recognition of two subjects responding to one another, but unfree.

Despite being coercive, Karatani emphasizes that mode of exchange A is not hierarchical, as the very demand for reciprocity impedes the centralization of power. It therefore cannot serve as the basis for state formation. Instead, the latter is founded on mode of exchange B, or plunder-redistribution. B is neither free nor reciprocal, and it is exemplified in both interstate warfare and in the various forms of taxation through which the state internally reproduces itself.

Next is mode of exchange C, commodity exchange, which is (formally) free but not reciprocal, in the precise sense that commodity exchange does not necessitate any feeling of mutual and personal obligation between party and counterparty. In place of such a feeling, there is only commodity fetishism, wherein material relations between people are mystified as social relations between things. That is to say, one recognizes at the other end of the exchange not another subject but only an instantiation of value. This mode, of course, finds its exemplary expression today in so-called ‘free markets.’

For Karatani, it is insufficient to characterize ‘capitalism’ as commodity exchange, which has been around for millennia. Rather, what is decisive about modern capitalism is that it has made commodity relations the dominant mode of exchange. While A and B continue to exist, they are subordinate to and reshaped by the dominance of mode of exchange C. For this reason, Karatani suggests that capitalism is not reducible to a historically specific mode of production but is also necessarily defined by a particular arrangement of these three modes of exchange, a “Borromean ring” which Karatani calls “capital-nation-state.”

Finally, however, there is mode of exchange D which persists right alongside these three other modes, albeit in a much more esoteric manner. It is described by Karatani as the “recovery” of A at a “higher dimension” through coordinated acts of “resistance” against the three other modes. Against B, D leverages the market relations of C in order to dissolve the coercive force of the state. Against C, D leverages the communal bonds of A to inhibit the accumulation of capital, namely, in “mutual-aid style” relations of reciprocity. In this way, D is supposed to follow the two axes down to the fourth quadrant and, by simultaneously contesting A, B, and C, precipitate a mode of exchange which is both free and reciprocal. In turn, mode of exchange D stands against capital, against nation, and against state in an analogous manner that Climate X—the anti-sovereign, anti-capitalist option proposed by Mann and Wainwright—runs against Climate Leviathan, Climate Mao, and Climate Behemoth.

We have thus found the true source of Mann and Wainwright’s debt. But what is it exactly that they owe Karatani? What is this “D” that is also an “X”?

In Wainwright’s interview of Karatani, both wrestle with the “aporetical” quality of Quadrant D. Explicitly, Karatani notes how he elected to call it X “because “communism” and “libertarian socialism” “carry negative and unintended connotations.” Moreover, Karatani says, it “does not exist in reality. It exists only as an idea (Idée).” And, as he says in a 2009 lecture:

Mode D does not exist in reality; if it does, it is only temporary […] The recovery of reciprocity is ‘the return of the repressed’, so as Freud remarked, it has something compulsive that transcends human will. In short, morality and religiosity do not reside in the superstructure, but rather are deeply rooted in the economic base structure. When seen in this light, we can easily understand Marx’s remark that the conditions of communism result from premises now in existence. Modes of exchange A, B, and C remain persistently. In other words, community (nation), the state, and capital remain persistently. We cannot clear them out. But we need not be pessimistic, because as long as these modes persist, the mode of exchange D will also persist. It will keep coming back no matter how much it is repressed and concealed. Kant’s ‘regulative idea’ is such a thing.

Mode D, Climate X, communist metaphysics: “regulative ideas” which are not and perhaps can never be fully determined, but which are in some way already active in the world ‘as if’ they were already real—namely, in a manner analogous to the return of the repressed, or as Karatani says elsewhere, to the unrepresentable “hole” which makes “systems of representation possible.”

Here, I want to suggest that what Wainwright and Karatani seem unwilling to attempt is what Marx, to my mind, would quite readily be doing. He would be offering a critique of “communist metaphysics” precisely from the perspective of the natural history whence it emerges. Put differently, he would be putting this Kantian philosopheme back into motion: if “communist metaphysics” is an idea, it is neither “unreal” nor “unrepresentable.” It is already something natural which has passed into thought, precisely on determined by an already existing, historically specific arrangement of the intercourse between humans and the world around them. What is meant by “unreal” here is nothing more than that the object of thought appears in itself but not for itself—that is, a thought whose referent remains external to consciousness, an object hence not (yet) conscious of itself.

For some reason (and I do not mean this merely as a turn of phrase; there is a reason!), Karatani, Mann, and Wainwright table the most important contribution Hegel makes against Kant, one which Marx certainly does not forget in this supposed “return” to the latter: the divisions between phenomenon and noumenon, nomos and phusis, “the political” and the “communist metaphysics” of X, are products of practical consciousness. That is to say, the divisions themselves arethe practical activities of conscious beings. In truth, then, the “communist metaphysics” of X, which seems to Mann and Wainwright so “aporetic,” is nothing but an ill-defined object of thought—namely, it is an ambiguous artifact of the notion of sovereignty they inherited from Hobbes (and after him, Schmitt) and which Karatani finds his own reasons to place in the mouth of Kant.

Recall that Kant’s “cosmopolitanism” for Karatani, of which the latter writes so affirmatively, explicitly presupposes that very same “deep-seated violence of human nature” of which Leviathan warns we must always be terrified. It is precisely with this image of an untamable Nature that the sovereign scares us into its arms, forces our trembling hands to sign its social contract. The sovereign wields the perennial threat of Nature against us (which, again, in the city becomes the threat of disorder inherent to the multitude), a threat which, as we saw with Derrida above, is in truth nothing but the reflection of itself. In Kant’s hands, of course, it becomes not the task of the sovereign, of pure decision, but that of critical philosophy to defend this world republic against “man’s nature.” And, in Karatani’s hands, it becomes the function of “transcritique,” that is, of a speculative movement toward X, or “communist metaphysics,” to correlate a practical critique of political economy with an ethical critique of instrumental reason.

But, I repeat: X is not “unreal.” It is much less esoteric than that. More simply, X is an insufficient thought. Insufficient because incapable of grasping in its concept that determinate separation of real/unreal from which it originates, that natural-historical activity from which ‘what needs to be done’ is currently present to consciousness only as ‘impossible’. Incapable, then, of grasping that universal history which the positing of X already implies—if only, at present, negatively.

In sum, I do not see any reason to make that already particular and determinate answer X any more mystifying than this: We do not know what to do about climate change because if we did, we would already be doing it. That object is necessarily one of critical, practical self-consciousness, an object which is its own method as much a method which is its object. This is the crisis of the current situation, and the problem is not at all with the lack of a response—whether from God, sovereign, beast, or X. As is always the case with apparent “aporias,” the problem is not the impossible solution but something latent in the posing of the problem ‘in itself’—that is, as I had suggested above, insofar as these notions of X, “the political,” and “communist metaphysics,” remain conditioned by that brutally false problematic of sovereignty.

On a Ground that Moves

Job’s Despair

Terrified, confounded, thoroughly distraught, all bleeding and trembling, Candide reflected to himself:

‘If this is the best of all possible worlds, then what must the others be like?’

-Voltaire21

On November 1st, 1755, an earthquake shook the Portuguese capital of Lisbon. To date, it is one of the deadliest natural disasters to ever hit Europe, killing tens of thousands and destroying around 90% of the capital port city’s buildings. Its occurrence on All Saints’ Day in one of the wealthiest and most religious cities in Europe confounded the ability of onlookers to reconcile the justice of divine violence with the sheer secularity of natural evil. Indeed, it was not only the poor or the wicked who were rendered to judgment that day but, disproportionately, the most righteous among us: thousands of churchgoers and clergymen were killed after fallen altar candles trapped them inside the churches where they congregated for the holiday, starting a firestorm which burned for hours and suffocated walkers by. The earthquake and subsequent tsunami destroyed the Royal Ribeira Palace, the Royal Hospital of All Saints, and the Lisbon Cathedral. Interpreting the wreckage as a rebuke of Leibnizian optimism, Voltaire famously scoffed, “this is the best of all possible worlds?”

As geologists like to recount, this particular natural disaster is also notable as a mythical origin of Enlightenment, insofar as the the secular response which followed the quake is said to have wrested Reason from both the Catholic Church and the royalist monarchy, once and for all. And, as they readily contend, Reason did not do so on its own: beneath the rubble of Lisbon, it discovers its compossibility with the rise of the modern state. One day after the earthquake, the Marquis de Pombal, de facto ruler of the Portuguese Empire, famously retorted, “What now? We bury the dead and take care of the living.” And, in turn, the Kingdom organized the “first modern disaster that compelled the state to oppose the notion of supernatural causation and accept responsibility for the reconstruction of the city.”22

Of course, it was not all stately goodwill: the Marquis had thought that reconstruction of the capital could help restore the Portuguese Empire to its former glory, and the declaration of an emergency was in no small part a concerted (and ultimately failed) political economic response to the burgeoning British and French Empires. The disaster no doubt also proved a convenient opportunity to subdue the Jesuit Order, once a powerful influence in Portugal, which after the quake vociferously warned against any state response which would appear to challenge God’s Judgment (and, as it happens, was to be expelled from the country four short years later).

Either way, declaring an emergency meant that the Portuguese Empire not only took direct responsibility for its citizens but explicitly committed the force and methods of scientific reason to this task. A great deal of effort was expended to assess the damage and coordinate the immediate needs of the city’s inhabitants, in particular through surveys administered throughout Portugal in the aftermath. The Chief Engineer of the Kingdom, General Manuel da Maia, was also consulted to submit a report for Lisbon’s reconstruction which he designed with mitigation of future earthquakes explicitly in mind. Limits were set concerning the maximum number of floors for the reconstructed buildings, and streets were widened to allow more space to flee from falling debris. Most famously from an architectural perspective, new buildings were to be reinforced with a wooden cage or “gaiola” which helped make them more resilient to seismic disturbances. Heavy import taxes were also instituted to help fund reconstruction, in addition to international aid from England, Hamburg, and Spain, among other states. Last, by decree of the Kingdom, price controls were set on food and other basic goods to prevent speculators from taking advantage of the hungry and increasingly desperate public. Thus the 1755 earthquake provoked an enormous mobilization of the Portuguese state and its best engineers and city planners against the forces of nature and on explicit behalf of the welfare of its citizens.

The Lisbon disaster did not miss the attention of a 31-year-old Immanuel Kant, who wrote three essays on earthquakes during the year following. Committed to “material” explanation during his precritical period, Kant saw the earthquake as an opportunity to combat appeals to the supernatural through a more sober, scientific study of its natural causes. And yet, in those tremors, the young Kant notes something if not supernatural nevertheless supremely uncanny about nature. Kant could not help but feel that, in the Libson earthquake, humanity had been struck disquietingly with the terror of the unknown: “we know the surface of the Earth fairly completely, but we have another world beneath our feet with which we are at present but little acquainted.”23 There is a deep dread felt by all, he writes, when the “ground moves beneath their feet.” When the habituation of the understanding breaks down, the subject feels its world no longer as a stable, indefinitely enduring frame but as something simultaneously fleeting and thrown into—a brief moment which reminds the subject that it never has stood upon stable ground.

And, as Thomas Moynihan and Luce Irigaray have both insisted, Kant’s fixation on earthquakes was not an inconsequential lapse in his “precritical” thought but a moment of profound insight which would return to him in his later philosophical project. Indeed, we see an aftershock of sorts of the Lisbon earthquake as late as the “Analytic of the Sublime,” the second book in the Critique of Judgment, where Kant describes sublimity as a feeling of Erschütterung, a tremoring. While Irigaray regards this moment in the Critique as indicative of Kant’s systematic anxiety over the possibility of “active matter”—a possibility which his entire critical project seeks to repress—Moynihan sees this lingering anxiety as what will find even more profound reverberations in the subsequent speculative thought of naturphilosophie, in particular the works of Ernst Haeckel, Lorenz Oken, and F.W.J. Schelling. In either case, just as above in my discussion of Karatani and “communist metaphysics,” we see here again a Kant who wants to spare something from the Concept, to keep the sublime a transcendent point of reference which continues to stand outside knowledge so as to provision its content—that is, its own boundlessness precisely as what makes us aware of our own fixity as subjects. Ground-in-itself, as it were: unknowable even as it makes itself known to us, again and again, every time the ground occasions itself to remind us that it, too, moves.

But in truth we already know all this. We already know the unknowable to be unknowable—and here let us be once again reminded of its other name, X—and in fact, precisely in knowing this, we know it to be not so unknowable as it appears. We already know that the ground never stops moving, that it is only us, caught uncritical and calcified in our subjective frame of reference, who could forget this. And so again, as I tried to argue above concerning ‘putting X into motion,’ what we also already know is this separation between knowing and not knowing is determinate. That is, we know that we (usually) don’t experience the Earth move even though we know that it does, that it spins and wobbles, that it orbits the Sun, and that, along with us and the rest of the Universe, it is hurtling toward the edge of space. And it is not just our scientific but our social consciousness which is already reflective of this separation which we impose on ourselves: we elect to reinforce our buildings to withstand earthquakes, for instance, not because we know or don’t know what will happen next but, more precisely, because we know that we don’t know.

We thus know quite intimately today the separation of the apparent fixity of Being from the vicissitudes of natural history. And to know that one doesn’t know—this is X, from which there are always two ways to proceed. Either you do as Mann and Wainwright do and hold this X as the unrepresentable, the ineffable, the incommensurable, the unconditional which conditions all other conditions, the impossible which grounds every possibility, the miracle borne to every event, the madness which subtends reason. In a word, you hold X to be wholly Other, simultaneously nowhere and everywhere, an inexhaustibly infinite and intangible resource for the Self. Or, you actually get to doing something, literally anything at all, and realize nothing ever remains unnamed, not even X. You realize X for its determinations, that is, its limits. You realize there was never any X to begin with, that there was never anything ‘outside’ to escape to, that the very separation between inside and outside had already been presupposed prior to your querying of it.

And when you realize this, you might then continue on to query all that which precedes you, all that which had led you to once see something quite thoroughly determined as this indeterminate X. And, perhaps, you will recognize in the determinations of X an entire world—indeed, what is X today if not the inverted register of our universal planetary history? What is X if not conditioned by this epoch in which we already find ourselves, this one of rampant, runaway climate change? X, put differently, is a response all too determined by the socionatural activities which are relentlessly making the planet warm, the glaciers melt, the sea rise, the forests burn, the lands spoil, and thousands upon thousands of species of animals and plants go extinct. X, its apparent indeterminacy already determined by this insatiable demand for buried sunshine, flared off back into the sky today—itself, ironically, without any apparent condition for doing so at all, without even the slightest restraint. X reflects not so much indeterminacy as the material dynamism of human existence on an unstable planet, the movement of “the political” on moving ground.

And it is no doubt true that, in spite of this inquiry into X, many of us still hold strong to a delirious belief that someone will, sooner or later, come out of nowhere and save us, make things stop moving again, found a new state. Sovereignty, we are told, is the only thing standing between us and ‘collapse’.

Well, the truth of it is, as the tradition of oppressed classes teaches us, we are already in a state of emergency; and the tragedy of it is that, in the face of natural history encroaching on all sides, the strongest among us have proven themselves capable of little more than miming the Marquis de Pombal. Ex post facto they do nothing but declare the exception, send out the surveys, dress the wounds, and get ready for the next one. Leviathan does not recognize its reflection in that natural world which it stupidly imitates, even as it pretends to have abandoned the latter beyond the city walls. It does not recognize itself in the ‘animal spirits’ it awakens in the markets again and again. It sees no trace of movement of the ground beneath its feet. All natural disasters appear to bourgeois consciousness as unhappy accidents, to be addressed by false and increasingly abstract mediations: non-binding international pledges, carbon budgets, catastrophe bonds. And this is to say nothing of the more direct, unignorably human threats to the global political order, which appear to Leviathan as the bestial, uncivilized pathologies of nonwhites, migrants, the poor, and on and on.

Leviathan, in brief, is completely incapable of comprehending its own collapse. So it is quite clear, asMann and Wainwright have vividly demonstrated, that neither capitalism nor sovereignty are up to the task of confronting climate change, of grasping movement on moving ground. But this failure of self-recognition also pervades Climate X. It and its “communist metaphysics” masquerade as inexhaustible appeals to alterity, but they are simply, quite mundanely, unfinished thoughts, and unfinished precisely because they are thoughts which are unrecognizable to themselves, thoughts which appear merely in themselves, as if undetermined by the natural history which already determines them and unnamed by the co-authors who have already named them. X affords only “aporia” precisely because it is itself a bastard child of Leviathan, an impossible solution because it condemns itself to the hopeless task of responding to an impossible problem: the paradox of anticipating a coming, harmonious planetary sovereignty built on the ground of capital’s inherent and irresolvable antagonisms.

But the impossible is certainly not the only possible way to pose the problem. It is, again, precisely the insufficiency of its positing which makes its solution, X, appear impossible. When that solution is taken to its limits, it invariably returns us to that universal problem it, to be sure, already implied. It returns us, that is, to moving ground, to the Anthropocene, to natural history. This is not, of course, to forsake all of the necessary criticisms which have been waged on all sides against abstract universals, and thus this is especially not to dismiss the very real differences of complicity, of responsibility, and of vulnerability for the sake of instead scapegoating some generic Human for our climate crisis. Rather, it is to recognize labor as the concrete universal conditioning our planetary existence. Without this self-recognition in Nature qua “man’s inorganic body,” as Marx had called it, any assertion of difference remains as abstract as the universal it refutes. It remains, in a letter, X.

Communism is not the substitution of one for another metaphysics but its determinate negation. It is, put differently, the real movement which abolishes the present state of things—including, especially, the metaphysics of its own (historical) presence. Communism is nothing if not really determining itself, not as an ideal but in and through the revolutionary subjectivity of labor which Marx called the proletariat. Communism is that praxis which unites the whole body of labor within and against capital, all that which separates living labor from itself. In this praxis called communism, undetermined thoughts like Climate X wither away, negated by the labor of self-recognition in the determinate, socioecological bonds of shared planetary existence.

There is simply no other way: no self-determination without the recognition of self as a being determined by other beings, no “equality, dignity, and solidarity” without a whole planet which concretely and objectively conditions these principles as practical, self-conscious activities. Communism is not and never has been an aporetic movement toward “regulative ideas”; it has never been a movement irremediably beyond itself. Communism is that praxis which discovers in and for itself its nature, its values, and its world in the determinate mediation of ideal and real, essence and existence, form and life.

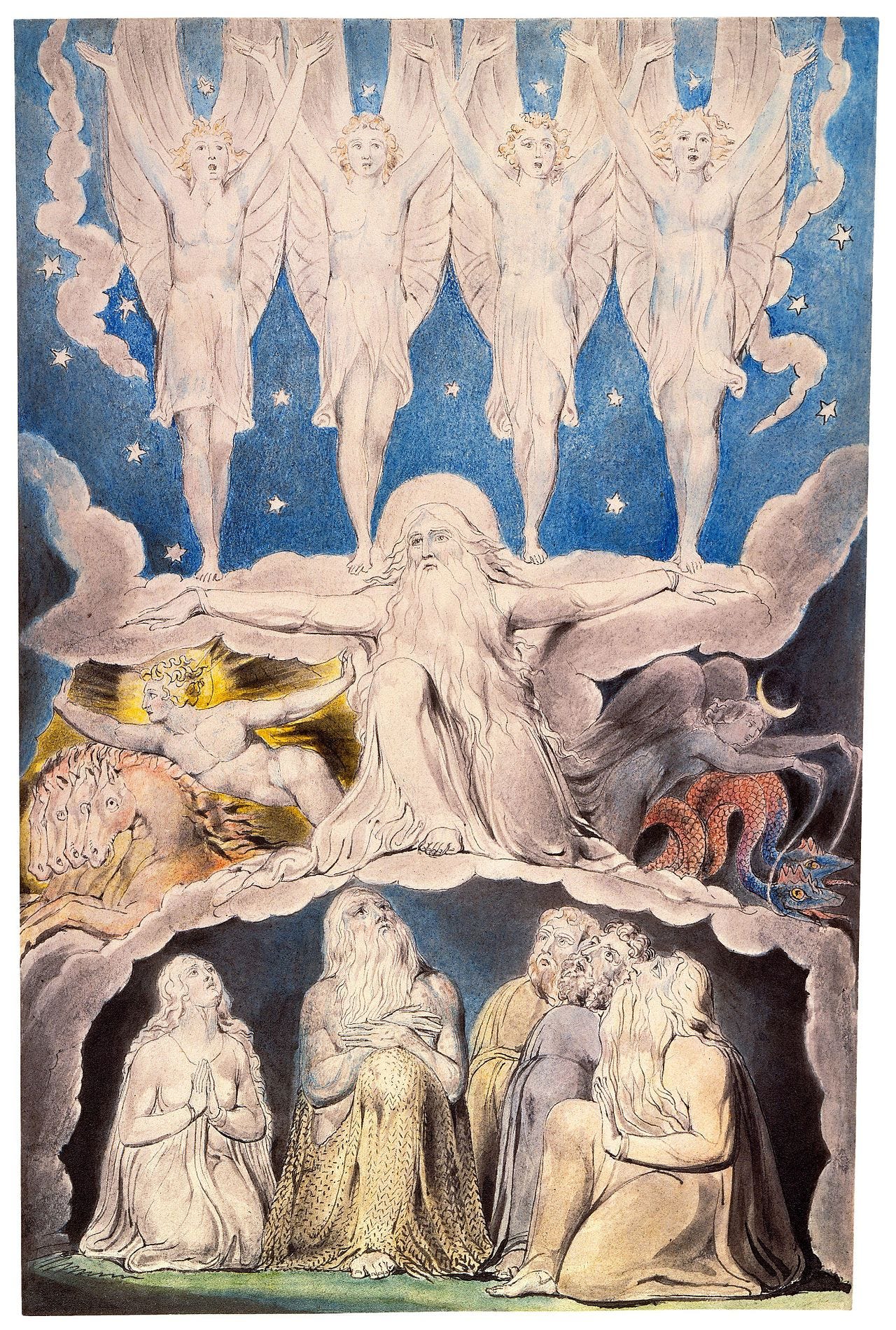

When the Morning Stars Sang Together

Mann, Geoff, and Joel Wainwright. 2018. Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future. London & New York: Verso, p. 15.

Inhabit. 2021. “Hell is truth seen too late: An interview with Joel Wainwright about Climate Leviathan and COP26.” Inhabit. <https://territories.substack.com/p/hell-is-truth-seen-too-late?s=r>

Pascal Blaise. (1995 [1670]). Pensées. In Pensées and Other Writings. Translated by Honor Levi and edited by Anothy Levi. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, pp. 1-181.

Hobbes, Thomas. 1998 (1651). Leviathan or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil. Edited by J.C.A. Gaskin. Oxford & New York: Oxford UP.

Schmitt, Carl. 1996 (1938). The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes. Translated by George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein. Westport, CT & London: Greenwood Press, 21.

Mann and Wainwright, 4.

Schmitt, 96.

Ibid, 98.

Mann and Wainwright, 2018, 94.

Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. The Time that Remains: A Commentary on the Letter to the Romans. Stanford: Stanford UP.

Hobbes, 1998 (1651), 7.

Derrida, Jacques. 2009. The beast & the sovereign, Volume I. Edited by Michel Lisse, Marie-Louise Mallet, and Ginette Michaud. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago & London: U Chicago P, p. 28.

Ibid, 55-56.

Tronti, Mario. 2019 (1966). Workers and capital. Translated by David Broder. London & New York: Verso, p. 336.

Mann and Wainwright, 2018, 136.

Karatani, Kojin. 2008. “Beyond Capital-Nation-State.” Rethinking Marxism 20(4): 569-595, 591-2

Mann and Wainwright, 2018, 129.

Immanuel, Kant. 1991 (1796). “Perpetual peace: A philosophical sketch.” In Kant’s political writings, Second Edition. Edited by Hans Reiss. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 93-125, 95.

Karatani, Kojin, and Joel Wainwright. 2012. “‘Critique is impossible without moves’: An interview of Kojin Karatani by Joel Wainwright.” Dialogues in Human Geography 2(1): 30-52.

Karatani. 2014. The structure of world history: From modes of production to modes of exchange. Translated by Michael K. Bourdaghs. Durham & London: Duke UP.

Voltaire. 2006 (1759). “Candide.” In Candide and other stores. Translated by Roger Pearson. Oxford: Oxford UP, pp. 3-88, p. 15.

Fuchs, Karl. 2009. “The great earthquakes of Lisbon 1755 and Aceh 2004 shook the world. Seismologists’ societal responsibility.” In The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake: Revisited. Edited by Luiz A. Mendes-Victor, Carlos Sousa Oliveria, João Azevedo, and António Ribeiro. New York: Springer, pp. 43-65, p. 57.

Kant, Immanuel. 2012 (1756). “Concerning the nature of the interior of the Earth.” In Natural Science. Edited by Eric Watkins. Translated by Olaf Reinhardt, pp. 337-365, p. 340.

taken from here: https://phases.substack.com/p/on-a-ground-that-moves