1. Risk and appeasement

Israel’s ongoing crisis – or ‘judicial coup’ in popular parlance – has elicited two opposite responses. The first comes from global rating agencies, economists and investment strategists who see Israel’s country risk rising. The opposite reaction, by Prime Minister Netanyahu and his acolytes, insists that the ‘coup’ is much ado about nothing, and that the country remains stable and strong as ever.

Begin with the risk assessors. Moody’s, for example, issued a special report, warning of a ‘significant risk that political and social tensions over the issue will continue, with negative consequences for Israel’s economy and security situation’. ‘The wide-ranging nature of the government’s proposals’, the agency argues, ‘could materially weaken the judiciary’s independence and disrupt effective checks and balances between the various branches of government, which are important aspects of strong institutions’. Although traditionally domestic and geopolitical tensions have spared Israel’s economy, ‘a serious escalation of tensions with the Palestinians could endanger improved relations between Israel and regional powers’. The agency further points to lower investment in Israel by high-tech venture capital and to the fact that the Israeli stock market trails the Nasdaq – developments it finds particularly disconcerting since high-tech firms are the growth engine of the country (Egan 2023).

This assessment is seconded by the CEO of the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE), who warns that ‘[t]he market’s underperformance since the beginning of the year […] indicates that Israel is moving further away from the world’s financial markets’ (Volinsky and Levy 2023).

Commenting in the same spirit, Citibank tells its clients that the Israeli situation has become ‘much more risky and dangerous’ and recommends that they hold on to their money until the dust settles (Anonymous 2023).

Morgan Stanley, too, sees ‘increased uncertainty about the economic outlook in the coming months and risks becoming skewed to our adverse scenario’. With the currency expected to drop, borrowing costs to rise, growth to weaken significantly and inflation to remain high, the bank has had no choice but to lower its Israel sovereign credit rating to a ‘dislike stance’ (Jones 2023).

The very same tune is played by Israeli high-tech protestors. ‘The judicial overhaul’, they posit, ‘will lead to the destruction of Israel’s economy and the elimination of the high-tech industry. These dire warnings are just the promo for the economic abyss this horrible government is leading us into: A sharp increase in the cost of living and interest rates and investor flight are only some of the economic woes that await us’ (Tucker 2023).

Netanyahu and his chamberlains, though, are unimpressed. These assessments, they say, are misguided momentary reactions. In a formally issued communiqué, they promise that,

when the dust clears, it will be clear that the Israeli economy is very strong. The security industries are bursting with orders. The gas industry is increasing exports to Europe and seven companies are now competing for tenders to explore for gas in Israel at an investment worth billions. Intel is planning its largest investment outside of the US ever and will invest $25 billion in Israel. NVIDIA is building a supercomputer in Israel and we are moving forward in AI, cyber and the manufacture of chips in Israel. Growth is increasing and inflation has been blocked. Regulation is being lifted and free market competition is increasing. The Israeli economy is based on strong fundamentals and will continue to grow under experienced leadership that is enacting a responsible economic policy’. (Netanyahu and Smotrich 2023)

2. The prophecy

Of course, the current Israeli crisis and ‘judicial coup’ – along with their opposing interpretations – did not spring out of the blue, but rather are the results of a long historical process. Here is some relevant background, summarized more than twenty years ago in the closing pages of our book, The Global Political Economy of Israel (Nitzan and Bichler 2002). The section from which we quote is titled ‘Global Accumulation, Domestic Depletion’:

Since the early 1990s, Israel’s ruling class incorporated itself into the new breadth order of transnational accumulation. The transition was presented, ostentatiously, as a victory for the country’s enlightened leadership. ‘Liberalism’, ‘peace’, and ‘high-tech’, they said, finally put Israel on the road to prosperity, and, initially, many were caught by the slogans. But soon enough reality set in. Neoliberalism, people discovered, was really a new power structure; peace, a cover-up for corporate peace dividends; and ‘high-tech’, a way to redistribute income and wealth. (348-349)

For [Israel’s] dominant capital, the neoliberal order of high-tech peace was of course a bonanza. Population growth [due to inward Russian immigration] provided the needed breadth; ‘peace’ and ‘high-tech’ attracted transnational investors; liberalisation opened up the world to capital flight; and the hype generated by these developments created immense capital gains. But the differential nature of the process was inherently redistributional, working to both re-divide the pie and restrict its growth. For the majority of the population, therefore, the new order was the problem, not the solution. (349)

In Israel,

the only miracle in this ‘high-tech’ drama, was the ability of dominant capital to suck in resources from the rest of society, while making everyone believe this was somehow in their best interest. And, indeed, for most of the population the consequences […] were dire […] During the early 1950s, ‘socialist’ Israel was still one of the more egalitarian countries, with the top 20 per cent of the population earning only 3.3 times the income of the bottom 20 per cent. This was certainly impressive, particularly relative to ‘free market’ countries such as the United States, where the comparable ratio was as high as 9.5. By 1995, however, after two generations of ‘Americanisation’, the situation was reversed. Israel was now the most unequal of all industrialised countries, with the ratio of the top to the bottom 20 per cent reaching 21.3, compared with ‘only’ 10.6 in the United States. (350-351)

Most politicians, in Israel and elsewhere, respond to creeping stagnation combined with upward income redistribution by conjuring the liberal wonders of trickle-down economics, augmented by government initiatives to boost technology and knowhow. And while initially Labour and Likud politicians hesitated to marshal this fine logic, Netanyahu loved to spell it out loudly and clearly:

There was indeed a ‘scary gap between rich and poor in Israel’, he admitted, but the way to resolve it was certainly not by handouts. ‘I don’t want to create jobs,’ he declared, ‘I want the entrepreneur to want’. The government, of course, was not planning to pull out completely, but rather to concentrate on education. Recognising that handing out state assets to private capitalists was bound to increase social disparity, Netanyahu concocted a brilliant solution. The state, he proposed, would plough some of the privatisation proceeds, along with donations from the lucky tycoons, back into a ‘special fund designed to close social gaps’, and into creating ‘thinking schools’ to help ‘balance the intellectual makeup of Israeli society’. (352)

In the concluding section of the book, titled ‘At a Crossroad’, we highlighted the growing conflict between Israel’s increasingly globalized dominant capital (‘local by denomination, global by accumulation’) and its domestic subjects, both Israeli and Palestinian:

This conflict may well mark the beginning of the end of Zionism. Until recently, Israeli capitalism went well with the Zionist project. The country’s ruling class, from its colonial beginnings, through its statist institutions, to its emergence as dominant capital, managed to interweave Jewish colonial ideas with capitalist praxis. During its ‘militaristic’ stage, it skilfully harnessed the ‘national’ interest to its differential accumulation. The social cohesion needed to sustain the war economy was cemented by religious and racial rhetoric, authoritarian welfare institutions, and frequent armed conflicts against external enemies. The cheap labour force in the equation was provided by the Palestinians. (354-355)

The shift toward transnationalism upset this delicate ‘equilibrium’. With the elite increasingly focused on the Nasdaq, the ‘high-tech’ business, and markets in the rest of the world, the prospect of peace dividends began to look much more attractive than dwindling war profits. Dominant capital was less and less receptive to the ‘garrison state’ and calls for an end to the Arab–Israeli conflict mounted. Once the ‘peace process’ started and the globalisation wagon began rolling, however, the Zionist package began to unravel. The domestic population, no longer needed for ‘national’ projects, was left exposed to the harsh reality of neoliberalism. And the Palestinians, whose cheap labour was now outbid by even cheaper ‘guest workers’, were given their ‘Palustan’ – a semi-autonomous entity, with half its original territory, no army, no economic sovereignty, limited water, complete dependency on Israeli infrastructure, and hundreds of Jewish settlements and roads crisscrossing their land. (355-356)

3. So, who is right?

With this twenty-year hindsight, we can now ask who is right – dominant capital or Netanyahu? Does the ‘judicial coup’ undermine democracy, upset the regime’s checks and balances, increase instability and ward off venture capital – or is there really nothing to worry about, with Israeli democracy remaining rock solid, liberalization and deregulation continuing, policy conducted responsibly and the economy growing and prospering?

In our view, both sides are correct – sort of – though for different reasons.

To see why, start with what most people tend to focus on: ‘leaders’. A typical global native with a short attention span and impatience for history is easy to convince that contemporary capitalism is directed by governments – or, more precisely, by their prime ministers or presidents. Presumably, these ‘leaders’ are the ones who unshackle capitalism from its regulatory hurdles, liberalize its trade and investment and unleash the enterprising power of laissez faire. Apparently, the more neoliberal the society, the greater the omnipotence of its top political figureheads – the ones who know how to make America great again, defend the Jewish people, restore Russia’s honour and bring back the glory of the Ottoman Empire.

Naturally, this myth has become prevalent in Netanyahu’s holy land. Until King Bibi’s reign, goes the argument, the Israeli economy was hamstrung by leftist bureaucracy and regulation, courtesy of the now-deceased Labour party. In his wisdom, Netanyahu managed to both repress inflation and rekindle growth – and he did so by doing precisely nothing; that is, by freeing the market to do its magic and by inviting his just-in-time capitalist cronies to join the party.

Our Global Political Economy of Israel, though, showed a very different history. Israeli privatization, liberalization and globalization started not with Netanyahu or any other neoliberal crusader, but with the ‘leftist’ Labour party, and they began not in 1996, when Netanyahu became prime minister, but in the 1980s (with some aspects, such as privatization, starting as early as the late 1960s). But since facts are no match for the post-truth capitalist media, Netanyahu can continue to tell his tale of saving Israel from Bolsheviks and bureaucrats, and of fighting relentlessly, together with his truth-seeking-law-abiding-free-market vigilantes, to uproot the remaining pockets of its deep state.

Let us examine this revisionist history a bit more closely, beginning with the globalization of Israeli capital and the country’s financial market.

4. The globalization of capital

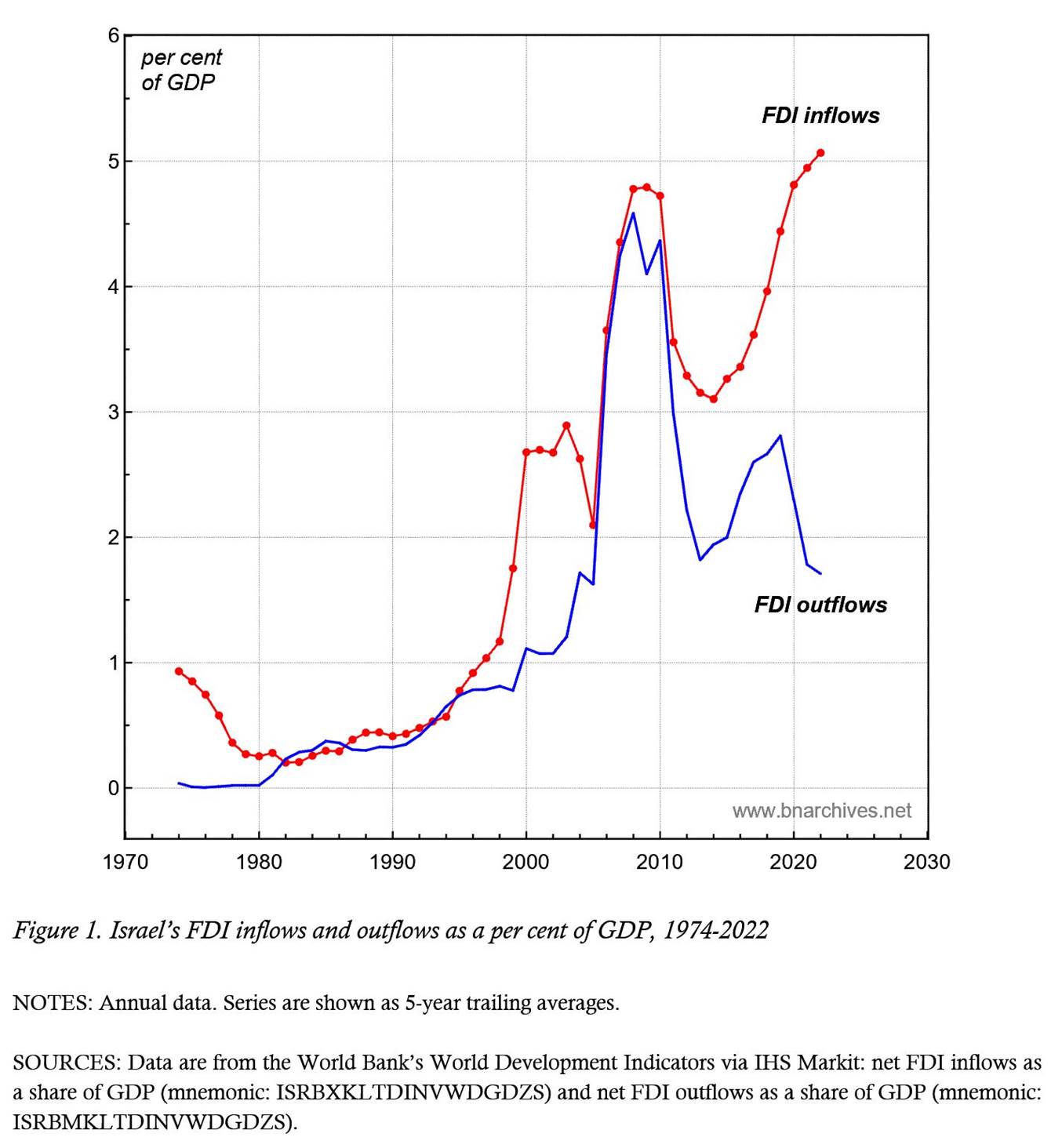

Figure 1 describes the country’s flows of foreign direct investment (FDI), expressed as a per cent of GDP, with the dotted red series showing inflows and the solid blue series depicting outflows. Both series are smoothed as 5-year trailing averages. [2]

Both flows started to rise in the 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s. By the end of the decade, inflows, showing the extent to which foreign owners increase their holdings of Israeli assets, rose to a level greater than 2 per cent of GDP, while outflows, indicating the degree to which domestic owners raise their non-Israeli assets, reached 1 per cent. This acceleration continued in subsequent decades, with FDI inflows and outflows reaching nearly 5 per cent of GDP in the late 2000s. Since then, inflows rose even higher, while outflows levelled off and declined (to compare, in the early 2020s, U.S. FDI inflows were equivalent to 1.5 per cent of GDP and outflows to 1 per cent, based on World Bank data).

The overall significance of this two-way capital movement is hard to overstate. As the process unfolds, with foreigners buying local assets and Israelis acquiring them outside the country, the nationality of capital gets increasingly blurred. By repeatedly crossing borders, the capitalist ruling class grows increasingly global and more flexible, and greater flexibility makes it less depended on and therefore less committed to any given country – a key point to which we return in the closing section of the paper.

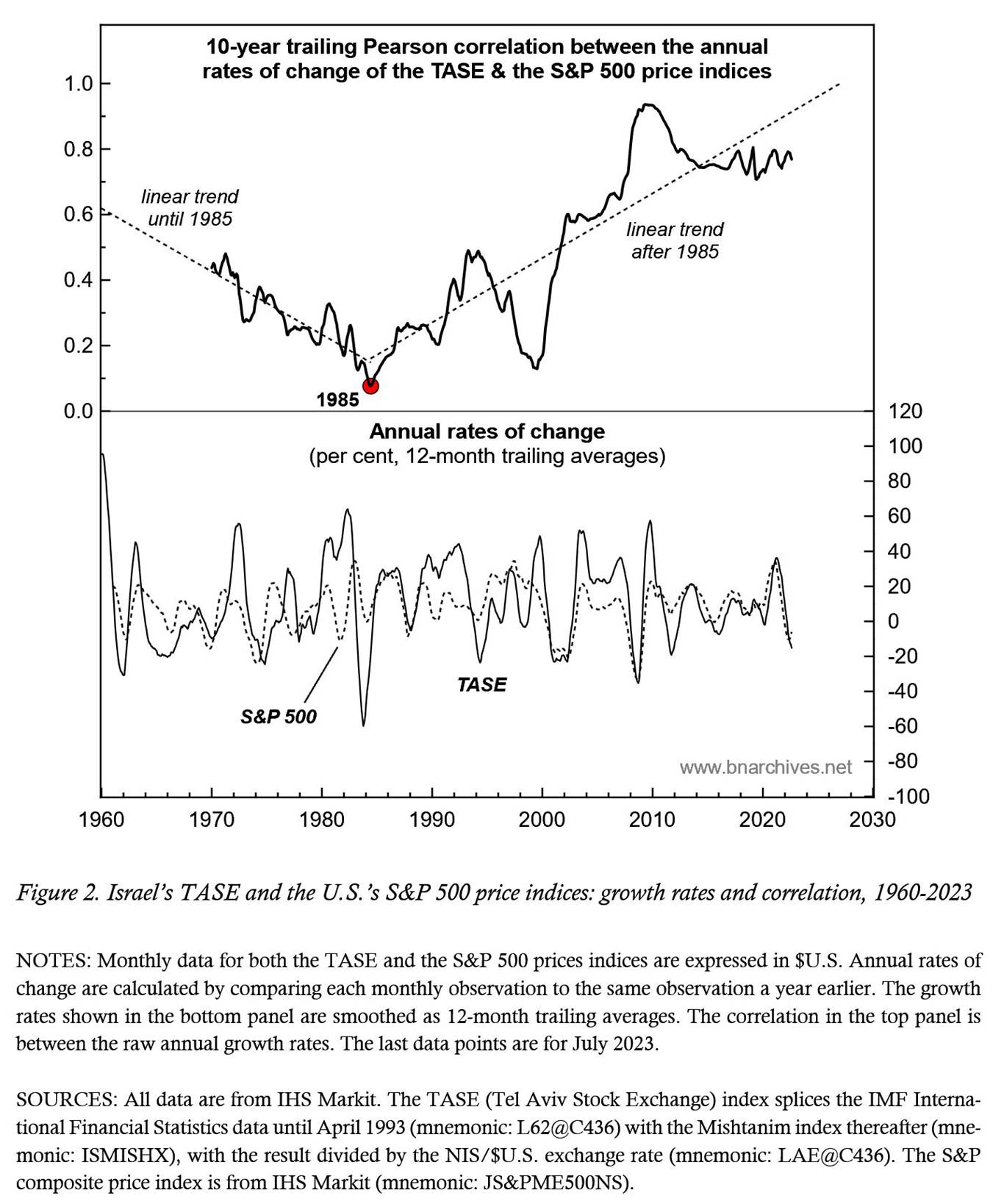

The globalization of Israel’s capital is shown from a different angle in Figure 2. The bottom panel depicts the annual rates of change of the monthly price indices of the U.S.’s S&P 500 and the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE), both smoothed as 12-month trailing averages. It contrasts the actual temporal oscillations of the two stock markets.

The top panel summarizes the relation between these two oscillations. It calculates the 10‑year trailing Pearson correlation coefficient between the two series in the bottom panel (using their raw rather than smoothed data), so that each observation shows their correlation in the previous 10 years. [3]

The V-shape pattern of the correlation demarcates the two eras of Israel’s global political economy – before the mid-1980s, and after. Prior to 1985, the oscillation of the two stock markets were only loosely related (in the 1970s, their correlation was around +0.3); and as the left downtrend indicates, this loose connection became even looser in subsequent years, with the Pearson coefficient dropping to almost zero during the decade ending in 1985. In this period, Israel was still locked in its depth regime of militarized stagflation, high-tech was not yet a buzz word, capital flows were restricted (Figure 1), and the exchange rate was regulated.

The turning point was 1985, when Netanyahu was still a mere envoy to the UN. In that year, the Labour government of Shimon Peres officially substituted neoliberalism for military Keynesianism, and the correlation between the Israeli and American stock markets started to trend upward. By 2010, it reached +0.94.

In other words, as the ownership of capital became increasingly global, Israel’s business activities, particularly in high-tech and weaponry, grew evermore aligned with those of the United States, its corporate profits oscillated more closely with those of American-listed firms, and its stock market came to mirror that of the U.S.

This integration helps explain current analysts’ concerns. For years, Netanyahu marketed himself as the main architect and chief promoter of the globally integrated Israeli market. And now, suddenly, there are signs of ‘investors’ flight’ and the TASE ‘moving away from the world’s financial market’ (note that, so far, the divergence, shown at the bottom panel of Figure 2, is miniscule: it amounts to Israeli stock prices continuing to downslide while the S&P 500 downtrend shows a tiny uptick).

In general, analysts have only superficial interest in specific details such as Israel’s democracy, its occupation of the Palestinians, its ecology and human infrastructure. Their main concern is the bottom line: namely, that Israel remains the region’s ‘rock of political, economic and social stability’ (a role for which it receives regular U.S. financial and military assistance), and that their capitalist masters continue to enjoy stable differential returns from their local financial portfolios. This is what Netanyahu keeps promising them, and his ability to deliver on that promise is now being called into question.

Netanyahu’s capacity to relentlessly peddle such promises is closely tied to his incestuous relation with Israel’s privatized media. For years, he has granted their owners exclusive rights, tax exemptions and other perks, to which they have reciprocated with nonstop adulating coverage and personal gifts. The symbiosis became so extroverted, that even Israel’s peevish legal authorities could no longer turn a blind eye and had to charge him with bribery, fraud and breach of trust.

It must be noted though, that on substantive matters, Netanyahu is not very different from his key political rivals and opposition parties. With few exceptions, all of them are nationalist and Zionist, they all support the Jewish settlement of the occupied territories and oppose meaningful Palestinian independence, they all believe in neoliberalism and privatization, and they all align, usually unconditionally, with dominant capital. The main difference is the extent of corruption and level of bluntness.

5. The ABCs of neoliberalism

The interesting question, though, concerns not Netanyahu’s liberal credentials and influence peddling, but the regime itself. Neoliberal ideologues and experts alike insist that deregulation, privatization and laissez faire more generally promote investment and growth and therefore the wellbeing of society – but do they?

As an idiomatic phrase, neoliberalism helps resurrect the lost illusions of eighteenth-century liberalism. But as a practical ideology and actual policy, it tends to do the exact opposite – i.e., to sustain and promote the capitalist mode of power and the oligarchic rule of dominant capital.

The media spotlights the regime’s political leaders, but truth be told, these so-called leaders seldom lead anything. Few of them possess the planning skills needed to guide society, and even fewer have the inclination – let alone the autonomy – to use them. For the most part, they act as go-betweens. They project downward onto the underlying population a façade of personal prowess and national authority, while accommodating their dominant capital masters with the right policies, legal protection, exclusive rights, government contracts, direct assistance and tax exemptions. More often than not, their shenanigans are soaked in favouritism, corruption and organized crime.

In the so-called democratic countries, ‘leadership’ positions nowadays are commonly held by media-savvy figures like Netanyahu, Berlusconi, Sarkozy, Trump, Bush Jr., and many of the recent prime ministers of Japan. In authoritarian regimes, where democratic paraphernalia is underrated or non-existent, the ‘commanding heights’ are typically held by megalomaniacs, deranged characters and criminals like Erdoğan, Putin, Lukashenko, Nazarbayev, the royal family of Saudia Arabia, the Iranian Ayatollahs, the Kim dynasty of North Korea, and the numerous rulers and military dictators of Africa and Latin America.

The role of neoliberal ‘leaders’ is intimately related to the fundamental distinction of neoclassical economics between the ‘private economy’ and ‘public politics’. When the Netanyahus of the world pretend to fight corrupt bureaucracy and remove red tape (say, by giving exclusive rights to their cronies), they rely on the basic assumption, reiterated in virtually every economics department, that ‘private=good, public=bad’; or more concretely, that the private economy is productive and efficient, while the public sector is parasitic and wasteful.

This assumption is the ideological bedrock of private capitalist property and the logical basis of mainstream economics. Productivity and efficiency, goes the neoclassical argument, can only be generated by utility-maximizing agents. Growth requires both inventiveness and frugality, and those traits can be ascertained only by the free-market interaction of rational individuals who seek to maximize benefits and minimize costs. This is why capitalism relies on private owners and competitive markets, and why it is the private profit-maximizing sector that invents, invests and moves society forward.

The public sector is not meant to – and being public, cannot – achieve those goals. Its purpose is not creativity and productivity, but redistribution of what already has been created. It rides on and exploits the private sector, usually with corruption to boot, and in so doing distorts private efficiency, crowds-out private investment and undermines private growth. Or so they say.

With this setup in mind, the best thing for everyone – including the poorer strata of society – is to make (inefficient) governments smaller, curtail (populist) public spending, reduce the (excessive) deficit, cut (wasteful) social programs and eliminate or at least reduce taxes on (productive-innovative) capitalists. To be fair, this to-do list should also include the mass resignation of (by-definition redundant) politicians and public servants who preach the neoliberal gospel while trying to equilibrate their marginal bribe with their marginal inefficiency.

The good news is that, by the 1980s, neoliberalism won the battle, or so we are being told. Governments the world over started to curtail their spending, reduce taxes, cut deficits and privatize public assets. True, there were corruption scandals here and there, and occasionally assets were sold for nothing to dear friends and close acquaintances. But as we all know, in a revolution, when you chop wood, splinters fly. All in all, the world is a much better place now. No more ‘illusion perdue’. Instead, we have increasing business investment, rising wealth and soaring financial markets. Public services have shrunk and been made private, but the reduction has been more than compensated for by booming investment, zooming growth and soaring standards of living for all. There is only one problem: this narrative is mostly fairytale.

6. Are governments getting smaller?

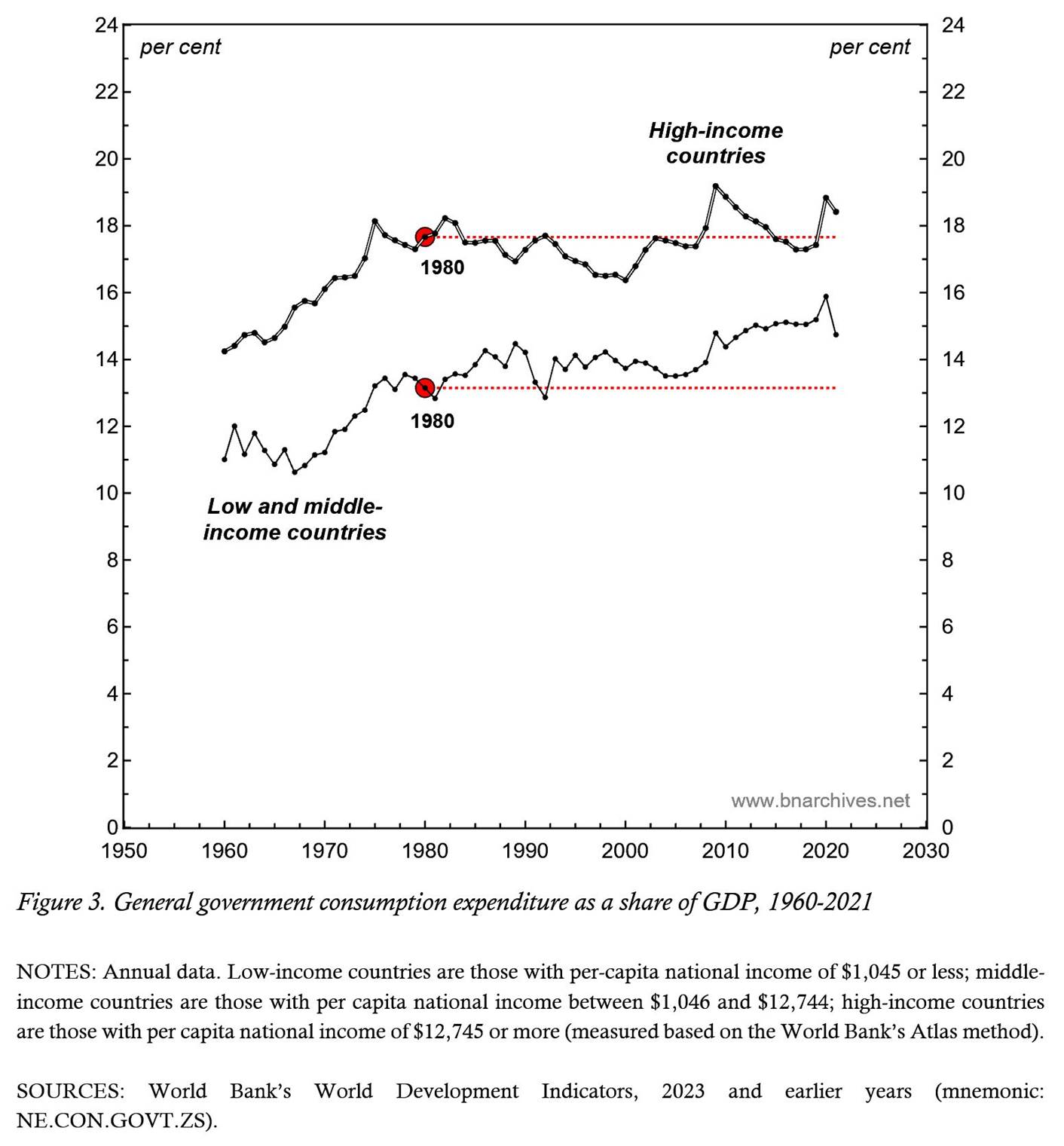

Start with the size of government. Figure 3 shows general government consumption expenditure as a per cent of GDP. Note that the spending pertains only to government purchases of goods and services; they do not include transfer payments – i.e., unemployment benefits, welfare payments and other handouts – for which the government receives nothing in return. In other words, this is a partial measure of the spending size of government.

The chart shows two series, calculated by the World Bank. The top series pertains to high-income countries, defined as those whose per capita national income in 2021 was $12,745 or higher. The bottom series covers low and middle-income countries, defined as those with per capita national income of $12,744 or less.

And lo and behold, the facts show a world turned upside-down: if we take 1980 as the beginning of neoliberalism, we must conclude that this new regime has made governments not smaller, but bigger!

In the rich countries, government spending during the ‘interventionist’ Keynesian era (1960-1979) averaged 16 per cent, compared to 17.6 per cent during the laissez faire period of neoliberalism (1980-2021), while in the poorer countries, the average rose from 11.9 per cent during Keynesianism to 14.1 per cent in neoliberalism. The latter group of countries is particularly damning to the conventional story, since it shows not only that neoliberal governments are bigger than their Keynesian counterparts, but that they keep growing!

7. Are investment and growth booming?

The other neoliberal promise, reiterated endlessly by laissez faire politicians and hard-core economic scientists, is that, once liberated from the shackles of government intervention and the welfare state, capitalism will soar on a wave of private investment – or, as Netanyahu put it, ‘I don’t want to create jobs, I want the entrepreneur to want’ (Nitzan and Bichler 2002: 352).

And yet, this promised privatized boom never happened. After the fanfare launch of neoliberalism, investment and growth, instead of accelerating, decelerated.

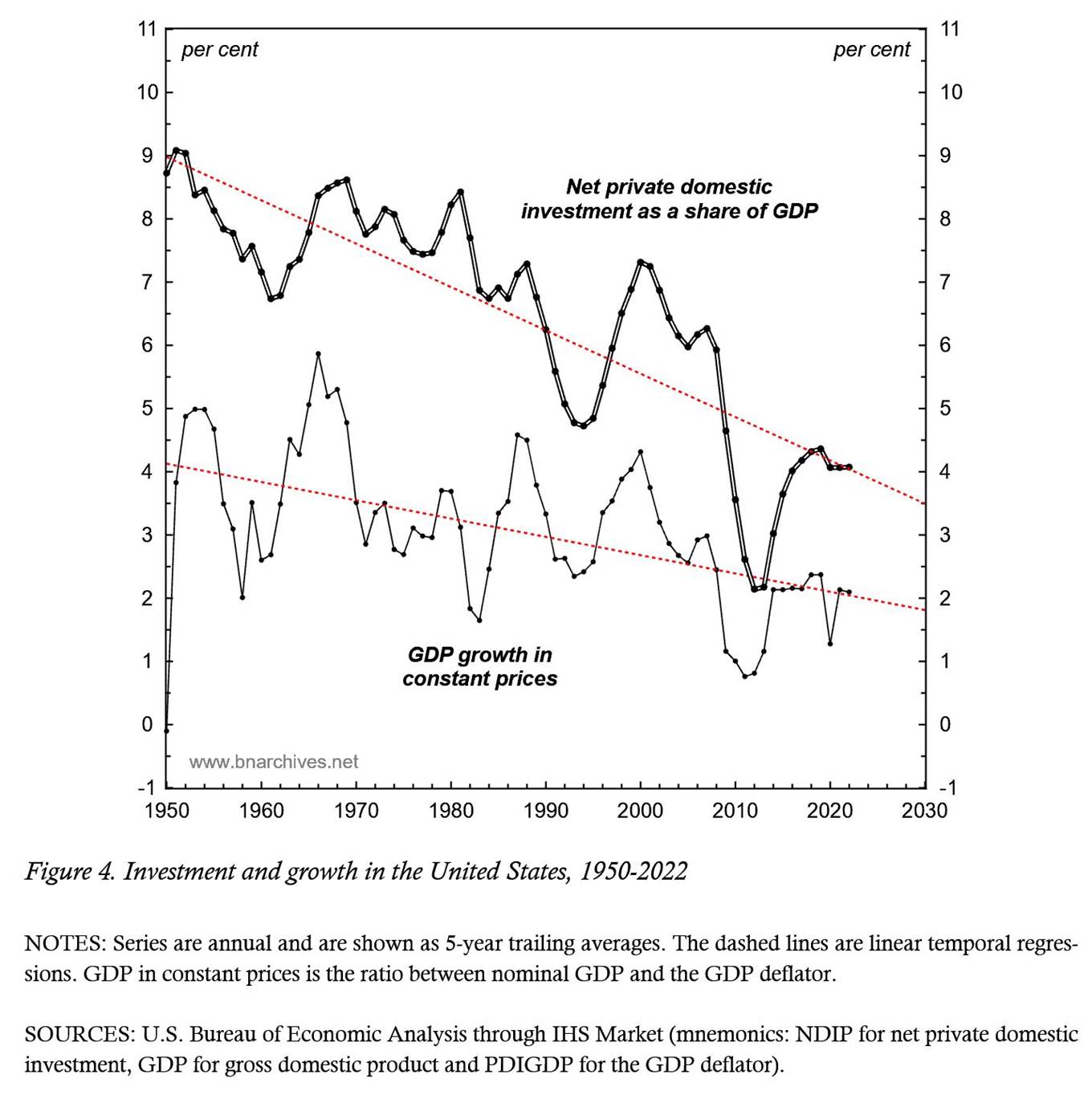

Figure 4 traces this process in the United States. The chart plots two series. The top one measures the share of net private domestic investment in GDP (i.e., gross private domestic investment less the annual depreciation of the outstanding capital stock). The bottom series measures the growth rate of ‘real’ GDP (i.e., GDP expressed in constant prices). [4] Both series are smoothed as 5-year trailing averages to accentuate their overall trends.

And the trends show that neoliberalism has failed to deliver. As with the size of government in Figure 3, here too, economic performance during the interventionist Keynesian period seems far superior to that of the hands-off neoliberal era. In the post-1980s period, net private domestic investment averaged 5.5 per cent of GDP, down from 7.9 per cent in the pre-1980 period (a relative drop of 30 per cent). Similarly, GDP growth after 1980 averaged 2.7 per cent, down from 3.7 per cent in the earlier period (a relative fall of 27 per cent).

It is worth mentioning here that neoliberalism emerged hand in hand with postmodernism, and perhaps not for naught. For both, dry facts are no match for the imagined reality. ‘What are facts?!’, a distinguished post-political economist asked us after we had presented her with data that refuted her claims. Everyone knows that statistics lie and that facts are concocted by the powerful to impose their will. Ignorance is strength, echo the fake-news leaders of postist neoliberalism.

8. On government intervention

But why has neoliberalism failed to deliver? How did it happen that governments grew bigger instead of smaller, and why have investment and growth plummeted rather than soared?

To answer this question, it is useful first to clarify the meaning of ‘government intervention’. After the Second World War, most Western governments – be they social-democratic, Keynesian or reformist – engaged in planning the social and technological infrastructures of their society. The fresh memory of the Great Depression, the recent experience of war mobilization and the alleged success of Soviet planning gave laissez faire capitalism a bad rap and encouraged long-term social policies that went beyond the short-term profit of business enterprise. Governments enjoyed concentrated power and were relatively efficient, while policymakers were still innocent of the rampant corruption that would later typify neoliberalism.

By contrast, neoliberal governments tend to be weak, with policymakers who lack the ability and will to plan socially, let alone plan for the common good. Their main preoccupation is legislation, policies, contracts and tax cuts to smooth the path to greater profits, particularly for dominant capital.

So here is the answer to the neoclassical puzzle of Figure 3: ‘government intervention’ is scaled not by the sheer size of the public sector, but by its ability to use public knowledge to plan the wellbeing of society. Neoliberalism reduces and dismantles this ability and in so doing makes government bigger instead of smaller. Today’s younger generation is less and less able to afford reasonable housing, quality healthcare and enlightened education, and is unlikely to receive sufficient retirement income. And as ‘leaders’ shirk and privatize their responsibilities toward the underlying population, inefficiency balloons, corruption flourishes, inequality skyrockets and government budgets inflate relative to the so-called dark age of Keynesianism (more on this process in Section 10).

These considerations also make it is easier to understand why the creation of new productive capacity has declined and growth decelerated (as illustrated for the United States in Figure 4). Rising inequality since the 1980s – relatively modest in the more enlightened European countries, steep in the hard-core neoliberal ones – has restricted the mass consumption of goods and services, while ongoing privatization has limited the need for new capacity. In parallel, the blank-cheque empowerment of dominant capital has allowed it to shift from greenfield investment which tends to create excess capacity, to mergers and acquisitions that boost concentration and differential accumulation, causing net investment to decelerate and overall growth to plummet even further.

9. Redistribution

Decades of neoliberalism have made humane, socio-economic and ecological planning increasingly difficult to achieve. This difficulty besieges even true-to-form parliamentary democracies that hold regular elections and keep the powers of their different government branches separate. In most countries, we witness one ineffective government replacing another. Even a five-sigma event, with a new enlightened administration eager to change the world substituting for a government of ignorant officials and plain criminals, will not do the trick. To be effective, the enlightened administration would have to replace most of the country’s existing civil, military and technological services, which, over the years, have been conditioned in universities, tech institutes and the armed forces not only to act neoliberally, but to think neoliberally. Today, there is not a single scientific centre in the world that can offer a theoretically informed practical alternative to neoliberal capitalism. In this sense, dominant capital has delivered a real knockout. Its neoclassical economics and neoliberal politics have gravely undermined the human spirit and clouded its future.

This reality, however dismal, completely debunks the common bifurcation of economics from politics, or capital from state. That duality was perhaps adequate for the late Middle Ages, when the industrious economies of the new burgs emerged amidst and against the power politics and endless violence of the feudal order. But nowadays, the distinction serves mostly as a thin veil for a tightly integrated business-state complex of concentrated power and strategic sabotage.

In our work, we have argued that capital is not a material economic artifact but commodified power writ large, and that this capitalized power discounts not only the so-called economic domain, but all organized power facets of modern society, including politics. To conceive capital as power is to realize that business hierarchies cannot survive a single day without the various institutions of government. And when income is redistributed upward and inequality rises, governments and corporations, particularly the dominant ones, become more fused and their capitalist mode of power grows more cohesive. In our view, this reality of upward income and asset redistribution on the one hand and an increasingly cohesive capitalist mode of power on the other is a key feature of the neoliberal regime, and it can be observed in virtually every country touched by this regime.

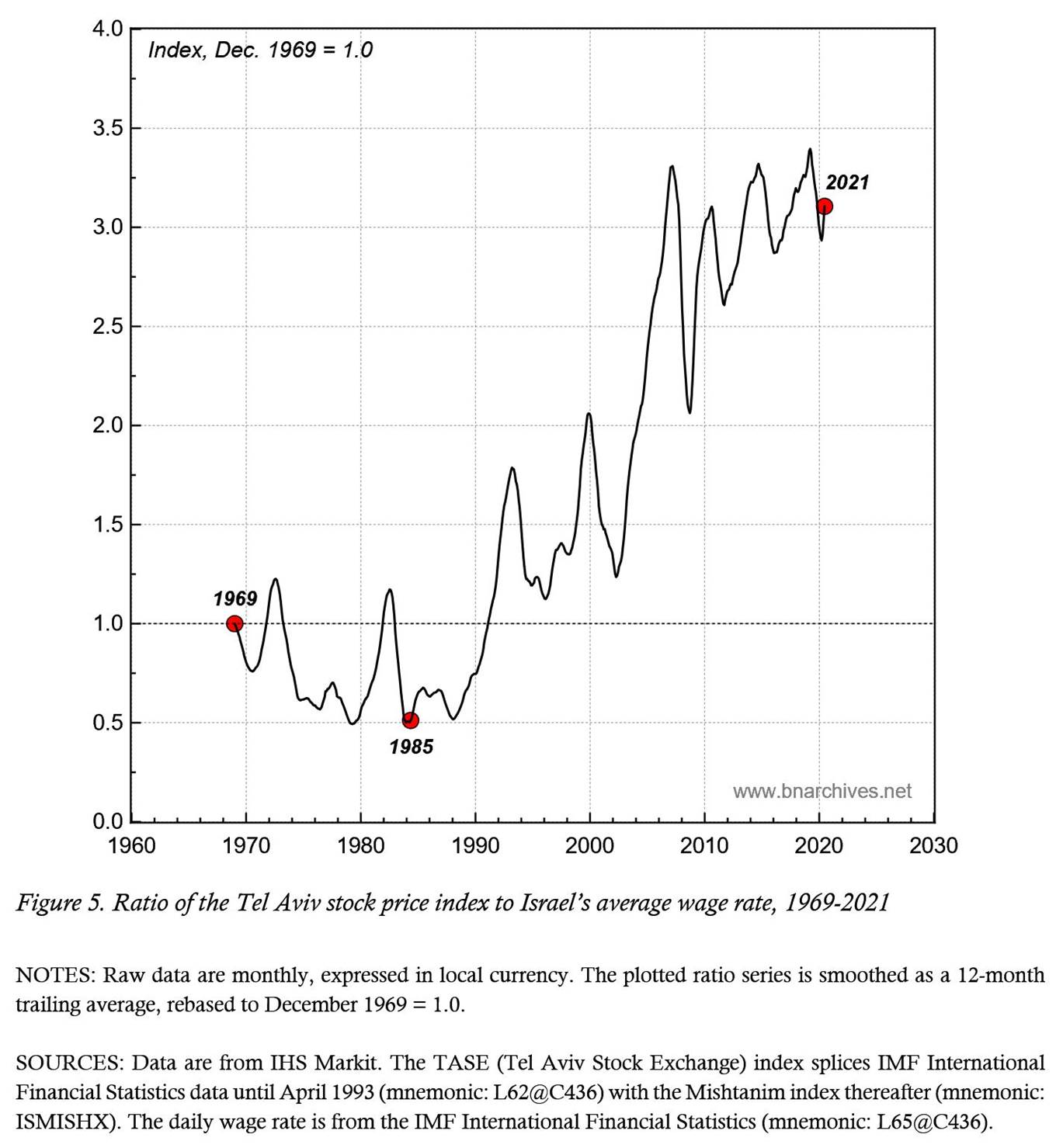

Figure 5 highlights this upward redistribution in Israel. Usually, the process is studied by dividing society into deciles or quintiles, measuring the income or assets of each group, and then assessing their skewness using a Gini Coefficient, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), or simply the ratio between the monetary size of the different groups.

Although we have used this method in some of our studies, its application is problematic on two counts. First, in many countries, the decile or quantile breakdown is inaccurate or simply non-existent; and second, in most cases, the data do not identify, at least not explicitly, the specific source of income (such as capital income versus wages).

Figure 5 bypasses these problems, however provisionally, by comparing the stock market price index to the average wage rate. The computation comprises three easy steps: (1) for every month, we divide the Tel Aviv stock market price index (TASE) by Israel’s average wage rate; (2) we smooth the resulting series as a 12-month trailing average; and (3) we normalize the smoothed result so that the first observation – in this case, for December 1969 – is made equal to 1 (to normalize the series, we simply divide every observation by the magnitude of the first observation; this division alters the absolute size of the observations, while keeping their relative magnitudes intact).

To interpret the figure, imagine a hypothetical capitalist in December of 1969 owning a proportional chunk of the Israeli stock market worth $1,000, and a hypothetical Israeli worker earning the average wage worth $1,000 a month. In that month, the ratio between the capitalist portfolio and the worker’s wage is exactly 1. [5]

From that month onward, the market value of the capitalist’s portfolio rises and falls with the stock market, the worker’s income goes up and down with the average wage rate, and the ratio between them indicates the differential performance of the capitalist versus the worker relative to their December 1969 ratio of 1.

The V-shaped pattern of the stock-price-to-wage ratio and its periodicity are consistent with the key processes we have discussed thus far – namely, Israel’s shift from Keynesianism to neoliberalism, the globalization of its capitalist ruling class, and the growing integration of its equity market with that of the United States.

During the 1969-1985 period, stock prices trailed wages, causing the ratio between them to drop by a whopping 50 per cent. But this was the abyss (for capitalists, that is). With the Labour government’s 1985 Stabilization Policy, Israeli neoliberalism started in earnest. Capital began to cross the border, both inward and outward (Figure 1), the Israeli stock market gradually synchronized with its U.S. counterpart (Figure 2), and equity prices soared far faster than wages (Figure 5). Over the entire 1960-2021 period, equity prices rose more than three times faster than wages, while in the 1985-2021 period, they increased six times faster. Curiously – though not surprisingly given the globalization of Israeli capital and its growing correlation with the U.S. stock market – the changes in the comparable periods in the U.S. stock-price-to-wage ratio were virtually the same as Israel’s!

10. ‘Leaders’, what are they good for?

Like every mode of power, neoliberalism too has a dialectical underbelly. For capitalized power to increase, capitalists must accumulate differentially; and differential accumulation means that income and assets get redistributed upward – from small capital to dominant capital; and, more generally, from workers and the underlying population to capitalist owners at large. This upward redistribution can be partly masked if the overall standard of living – measured in capitalism by per capita ‘real’ GDP – grows rapidly. But neoliberalism is characterized by decelerating growth (as illustrated for the United States in Figure 5). Indeed, slowing growth (which typically comes together with inflation) is a major power lever that capitalists use to redistribute income and assets in their favour.

The net result for the underlying population is stagnating standards of living (in the United States, the purchasing power of the average wage earner has hardly changed since the 1980s), chronic unemployment, deteriorating public services, rising crime and incarceration and lingering insecurity more generally. This situation, typical of the neoliberal epoch, creates a permanent threat of instability and, if the conflictual redistribution intensifies, even of ‘ungovernability’.

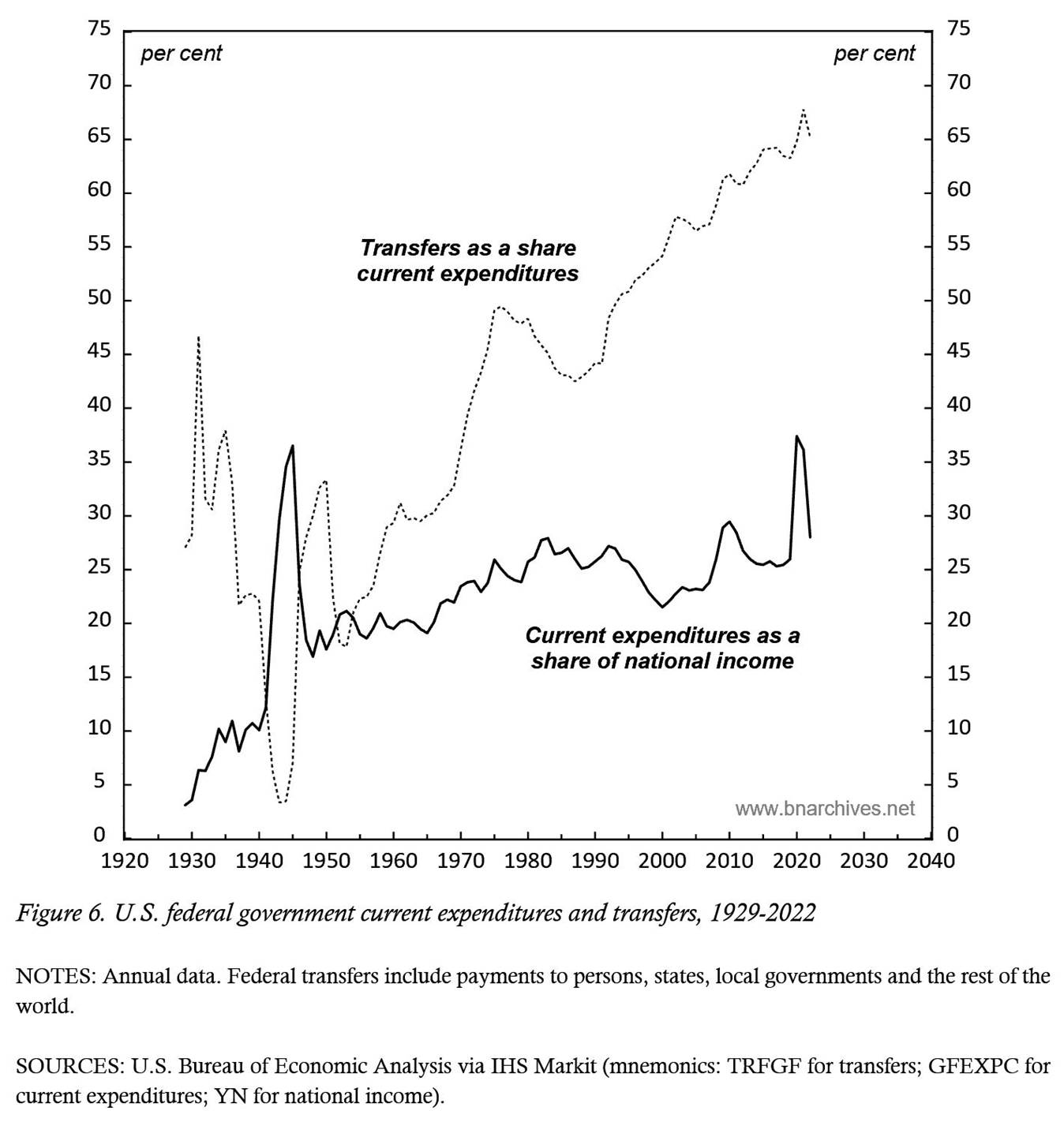

The ruling class tends to respond to this threat in two ways. The first response is illustrated in Figure 6. The chart shows two measures of federal government expenditures in the United States. The solid series depicts the amount spent by the federal government on goods and services as well as transfers, measured as a share of U.S. national income. The dashed series shows the share of transfers in overall federal government spending.

As the figure indicates, the overall federal spending share of national income has trended upward for nearly a century, but the composition of these expenditures shifted markedly. Until the mid-1950s, spending was relatively discretionary (controllable, in professional lingo) and was earmarked primarily for goods and services: it rose rapidly with anti-Depression pre-Keynesianism in the early 1930s and with war mobilization since the late 1930s, and it dropped steeply as the war ended and military spending subsided. The central role of discretionary spending on good and services during that time is shown by the fact that the share of transfers in federal spending (dashed line) moved inversely with the overall federal spending share of national income.

This inverse relation flipped in the mid-1950s. The overall federal spending share of national income continued to trend upward, but this time, it was the relatively uncontrollable part of the federal budget – mostly transfer payments for the unemployed and welfare recipients – that took the lead. By the birth of neoliberalism in 1980, transfer payments reached nearly one half of all federal government spending. By the early 2020s, they exceeded 65 per cent.

Now, here is the thing. In the United States, rising capitalized power served to impoverish a growing chunk of the underlying population; this growing impoverishment upped the ante of instability and even ‘ungovernability’; and this rising threat made it necessary for the federal government to boost transfer payments in order to legitimize the conflictual process of capitalization and appease the masses, however half-heartedly and meekly.

And this is where a new species of ‘leaders’ – the media star – became useful. This new breed, typified by characters like Trump, Erdoğan and Netanyahu, adds little of substance to the neoliberal process, but it offers a cheap way to legitimize its havoc and pacify the agitated proles.

The new ‘leaders’ tend to view themselves as supermen (women rarely display such delusions). While in office, Trump repeatedly boasted he was the best in practically everything he did (and didn’t do), including making America great again. Similarly, Netanyahu seems convinced he has barehandedly redeemed Israel (read the Jewish people), fortified its security and economy, invented its high-tech and supercharged its productive capabilities (maybe by undermining higher education in favour of religious and ultra-Orthodox schooling). And now, as inequality soars, education crumbles, health-services fall apart and organized crime flourishes, he and his goons stoke the fire by peddling racism, aggressive settlements and Judeofascism more generally for ‘the glory of the State of Israel’.

Curiously, organized religion, the most ancient technology in the legitimation arsenal, is also its most cost-effective. This technology works particularly well for Erdoğan in Turkey and Netanyahu in Israel, where the Islamic and Rabbinate churches encourage ignorance, obedience, female inferiority and a high birth rate of loyal future voters. Elsewhere, though, particularly in Western Europe and Japan, the middle strata have managed to counter the rule of capital, at least in part, by limiting the growth of both population and religion.

11. Stability versus risk

Having surveyed the scene and outlined some of its underlying processes, we can now better assess who is right: the business analysts of dominant capital who fear that risk is rising, or Netanyahu and his crew who promise that all is well in Bibi-land. As we said upfront, in our opinion both are correct, though for different reasons, and below we summarize why.

In the short term – say, a year, give or take – Israel’s macro performance could very well meet the global average. Here is a plausible, analyst-like scenario of how this process might unfold.

Arms exports will continue to boom, the corrupt processes of privatization will go on unabated, cronies will receive their exclusive rights, and the government will keep announcing new initiatives to de-regulate, de-bureaucratize and de-monopolize Israel more generally.

In this scenario, Netanyahu’s government will continue attacking the courts and alter/dismantle key aspects of the legal system, starve the secular education and health systems of funding and autonomy and neglect the country’s physical infrastructure and ecology – and all that, while encouraging the already high birth rate of religious Jews and pampering their radical right-wing militias. The government will also maintain and even increase its pressure on the Palestinians, while allowing private settler gangs, with enthusiastic support from their Rabbis, to harass, expropriate and hunt down Palestinians in their towns and villages.

On the other side of the conflict, the shaky and corrupt Palestinian ‘autonomy’ will remain caught between a rock and a hard place, subject to pressure from Israel on the one hand and from criminal gangs integrating into the anti-occupation struggle on the other – and all that, while watching local Islamic militia, both Suni and Shia, oppressing and terrorizing the Palestinian population, with generous backing from various foreign governments and organizations.

Now, the fascinating thing is that, despite this seemingly complex conflict, with much smoke and many mirrors, so far, Israel’s political map has remained pretty much unchanged.

As these lines are being written, the country’s anti- and pro-government demonstrations continue, as do the mutual accusations, mounting threats and disruptions to critical systems, including the military. King Bibi, the prime minister, is on trial. His behaviour remains psychopathic, if not criminal. He cannot speak without lying. His government, stuffed with yea-sayers, including semi-illiterates, plain thugs and convicted criminals, is hardly functional. And yet, half the so-called Jewish population (including Hebrew speakers who consider themselves ‘secular’) continues to support Netanyahu’s government. And it gets better: if we count those who support either the government or its main opposition parties, we get 80-90 per cent of the Jewish voters – all of whom stand for right-wing racially-based neoliberalism, oppose a Palestinian state and are ready to give the domestic Arab population no more than a token second-class status. And if that were not enough, half the domestic Arab population supports nationalist-religious parties as well! In other words, for the time being, Netanyahu is right. The Israeli regime remains stable and predictable.

But the dominant-capital analysts also have a point. Netanyahu keeps telling them to ignore the anti-government protestations, and that, contrary to the slogans of flag-waving anarchists, his legislative changes are meant not to bring dictatorship, but strengthen democracy.

Now, as noted, analysts care little about democracy, the separation of powers, the court system – and even privatization, for that matter. These are mere pixels, rubrics to be ticked in their standardized Excel sheets. For them, the bottom line is stability – or ‘governance’, in their ruler’s lingo. To get a sense of the stakes here, recall that, during the 1920s and 1930s, many British and American analysts favoured the radical right-wing regimes of Italy, Germany and other European countries, which, in their view, helped block communism and anarchy, bringing much needed order and tranquillity to the defeated side of the First World War.

But then, in the longer run, even Bibi the magician cannot make a regime based on ever-growing power more stable. This is a general point that goes beyond the specific case of Israel, and it is worth making, however briefly.

The conflictual growth of capitalized power has inner asymptotes, or limits. Differential capitalization relies on the upward redistribution of income and assets, and at some point, the additional sabotage required to push redistribution further becomes difficult if not impossible to sustain, at least under the facade of liberal democracy. As the purchasing power of workers erodes, the profit of small capitalists falls, social services for the masses deteriorate and taxes on corporations and the rich drop, the power regime becomes increasingly brittle, and the risk of systemic crisis mounts (Bichler and Nitzan 2012, 2016, 2020).

In our view, these systemic risks are inherent, and nowadays they are visible not only in individual countries, but globally. Simply put, the nation-state model, which emerged with the French Revolution based on the British and Dutch liberalism of the seventeen and eighteenth centuries, is no longer congruent with differential accumulation by dominant capital on a world scale.

In Israel, this mismatch is heightened in two opposite ways. On the one hand, we witness the growing globalization of the ruling class for whom Israel has a become a vendible slice in a transnational portfolio (Figures 1 and 2) – a slice they think they can always sell if push comes to shove. On the other hand, we see increasing local inequality and the pauperization of the underlying population (Figure 5), mounting oppression and expropriation of the Palestinians, and rising right-wing religious and racist politics.

Here is how we imagined this process unfolding more than twenty years ago, in the closing paragraph of The Global Political Economy of Israel:

Israeli capitalism is clearly at a crossroads, and its future, perhaps more than ever, is bound up with global developments. Until recently, transnationalisation lent strong support to reconciliation with Arab neighbours, and to ‘peace’, if only paternal, with the Palestinians. The recent stalling of global breadth, however, has thrown a monkey wrench into the process. If the reprieve proves temporary, there may still be a remote chance of resolving the regional conflict. Breadth requires political stability, and dominant capital, both in Israel and globally, would seek a settlement to calm things down. But with religion winning the hearts and minds of the underlying population, time is running out. And if instead of renewed breadth, global capital settles in for an extended period of depth, the conflict and violence associated with such a regime could prove devastating for Israel and for the region. (2002: 357)

Dominant capital cares about its capitalized power more than anything. That’s what makes it tick. But the ongoing globalization of its ownership gives its rulers the impression they can always go elsewhere, and this impression makes them increasingly indifferent if not blind to the damage, instability and havoc they cause, as well as less likely to compromise or shift direction.

The specific features of Israel – a small country whose capital concentrated very rapidly and was easy to transnationalize; ongoing international hostilities and the occupation of another people; and simmering religious, ethnic and racial conflicts in a region whose climate is warming faster than any other – make it a case study for pending collapse. But similar or parallel features exist in many other countries, including the United States, and they too could meet a similar fate.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Work on this paper was partly supported by the SSHRC.

[2] FDI refers to purchases accounting for 10 per cent or more of the acquired asset. Smaller acquisitions are considered portfolio investments.

[3] The Pearson correlation coefficient ranges from +1 (perfect positive correlation) and –1 (perfect negative correlation).

[4] In our own work, we criticize the notion of ‘real’ economic aggregates, arguing that the very concept as well as its measurement are deeply problematic. But in this paper, we examine not our own claims, but those of neoliberals, so we use their overall ‘real’ growth measures with liberty.

[5] Strictly speaking, the capitalist’s portfolio is a ‘stock’ at a point in time and therefore a pure monetary magnitude (in NIS), while the wage rate is a ‘flow’ over time (NIS/time). Consequently, the ratio between them is expressed in units of time = $/($/time).

References

Anonymous. 2023. Citi Lowers Israeli Growth Forecast, Citing ‘Recent Turmoil’ Over Judicial Overhaul. The Times of Israel, August 3.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2012. The Asymptotes of Power. Real-World Economics Review (60, June): 18-53.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2016. A CasP Model of the Stock Market. Real-World Economics Review (77, December): 119-154.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2020. Growing Through Sabotage: Energizing Hierarchical Power. Review of Capital as Power 1 (5, May): 1-78.

Egan, Matt. 2023. Moody’s Warns Israel Faces ‘Significant Risk’ of Political and Social Tensions that will Harm its Economy, Security CNN Business, July 25.

Jones, Marc. 2023. Morgan Stanley Cuts Israel Sovereign Credit to ‘Dislike Stance’ After Judiciary Changes. Reuters, July 25.

Netanyahu, Benjamin, and Bezalel Smotrich. 2023. Joint Statement by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich in Response to Moody’s Special Report Israel, Prime Minister’s Office, Government Press Office, July 26.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2002. The Global Political Economy of Israel. London: Pluto Press.

Tucker, Nati. 2023. Moody’s Says ‘Earlier Concerns’ for Israel Materializing After Key Judicial Overhaul Law Passes. Haaretz, July 25.

Volinsky, Jenya, and Gilad Levy. 2023. Tel Aviv Stock Exchange CEO Warns ‘Israel’s Economic Power in Danger’ Due to Judicial Overhaul. Haaretz, August 9.

taken from here